Wimbledon 2015: Why Rafael Nadal's 'shock' exit is no shock

- Published

- comments

Wimbledon 2015: Dustin Brown stuns Rafael Nadal

Wimbledon 2015 |

|---|

Venue: All England Club Dates: 29 June - 12 July |

Play: Outside courts 12:15 BST; Centre Court and Court One 13:00 BST |

BBC coverage: Across TV, radio and online with up to 15 live streams available. Read More: TV and radio schedules. |

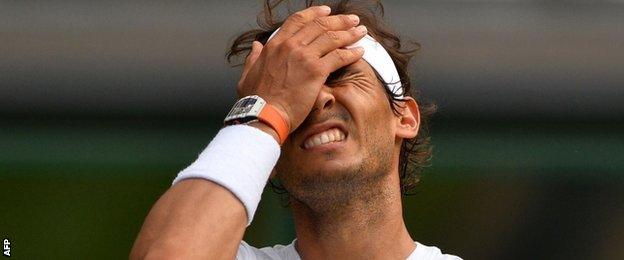

The great shock of Rafael Nadal's shock exit from Wimbledon at the hands of previously anonymous qualifier Dustin Brown was that in some ways it was no shock at all.

Nadal is a 14-time Grand Slam champion. He triumphed in the greatest Wimbledon final of all time. He has a forehand that is less a groundstroke than a superpower.

And his past four Wimbledons now look like this: 2012, loses to world number 100; 2013: loses to number 135; 2014: loses to number 144; 2015: loses to number 102.

And yet. For all that we should be used to the sight of the once invulnerable giant of the game reduced to the role of ancient monument to be repeatedly defaced, there is still fresh astonishment in watching it happen once again.

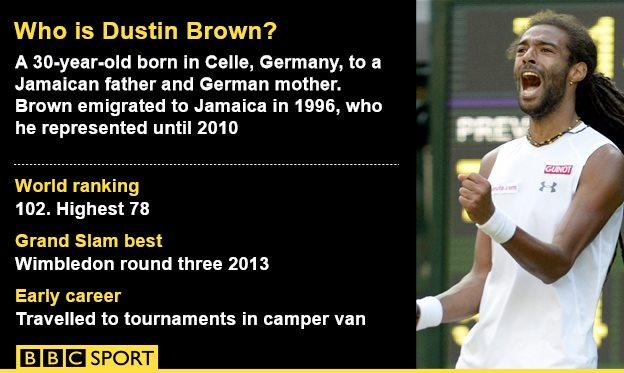

Nadal had never lost to a qualifier at a Grand Slam in 21 meetings. Brown had never before beaten a seed at a Grand Slam event.

Brown may have won the only previous meeting between the two in straight sets, just over a year ago and also on grass. But this was his first time on Centre Court. He played four hours of doubles (and lost) the day before.

Nadal has earned almost £50m in prize money alone. Brown has no coach and has to pay for his own racquets.

Nadal last won the men's Wimbledon singles title in 2010

The decline of a great

Even as the Centre Court crowd thrilled to Brown's extravagant serve-and-volley game, there was a parallel sense of mourning for the death-spin of a former darling.

Nadal has lit up this court like very few others, his escalating grass-court rivalry with Roger Federer culminating in one fabulous final in 2007, external and then, a year later, a match that quite comfortably went further still.

To watch a man famed for his relentless defence pulled apart by a 30-year-old who has only won four matches at Grand Slam tournaments in his entire career was simultaneously exhilarating and wretched.

But it was in the demise of that once-wonderful forehand that the passing years were most clearly visible.

Brown's brilliant start to Nadal match

This was always the great bedrock to Nadal's game, a weapon that could dismantle the best and intimidate the pretenders. Its whipped power and top-spin drove opponents back. Its depth left them reeling on the ropes.

On Thursday it was instead a virus, a flaw that opened great holes in his own defences. Too often it was short. Frequently it was mistimed. Repeatedly it sat up when before it had fizzed past chins or crashed into corners.

When Nadal lost to Steve Darcis in the first round here in 2013, he did so having secured his eighth French Open title a few weeks earlier. A few months later he would win his second US Open title and reclaim the world number one ranking.

Even last year, in crashing out to Nick Kyrgios, then a teenager, he did so having won his 14th Grand Slam in Paris in the same month.

Now? Now Lukas Rosol, his unexpected assassin in this same arena in 2012, no longer feels like the answer to a pub quiz question of the future. How can he be, when he is no longer the man who toppled the king but merely the first of four?

Dustin Brown has a large tattoo of the face of father Leroy on the left side of his body

A future burdened by the past

The patterns do not look pretty for Nadal, and not only because he has now failed to make it past the quarter-finals of the first three Grand Slam events of the year for the first time since he was a callow 18-year-old.

In the past six months he has lost in the first round of the Qatar Open to the unheralded Michael Berrer, currently ranked 139th in the world, lost to the Czech Tomas Berdych in straight sets in the quarter-finals of the Australian Open having gone into the contest on a 17-match winning streak against his opponent and lost early at Indian Wells and the Miami Open.

More tellingly, the King of Clay went through the entire season on his favourite surface without a single tournament win - losing in straight sets to Andy Murray in Madrid, where he has been crowned champion five times in the past; losing to Stan Wawrinka in the quarter-finals in Rome; getting beaten by Novak Djokovic in the quarter-finals at the French Open in Paris, after 39 consecutive wins at Roland Garros stretching back six years. For the first time in a decade his ranking has slipped outside the world's top five.

John McEnroe, three-time Wimbledon champion |

|---|

"Five hundred professional tennis players are inspired to hang in for a couple of years longer because of what they have just seen there. Nothing is impossible. Brown's level of play on this court was spectacularly high." |

At 29 years old you would hope he has time to arrest this precipitous slide. Federer is 33, and managing to make his own inevitable decline a much shallower one.

But Nadal is an old 29, this is his 15th season as a professional, his long-term tendonitis at best managed but never gone, his body increasingly struggling to cope with the immense forces he puts through it.

Then there is the confidence that allowed him to achieve the near-impossible - winning those record-breaking nine French Open titles, dethroning Federer in his own adopted kingdom.

"Part of the problem when other players have seen you being beaten is that it adds to their self-belief," says Tim Henman, Britain's former world number four.

"Dustin Brown will have looked at what Kyrgios, Darcis and Rosol have done against Nadal at Wimbledon in the last few years and said, 'They have beaten him, why can't I?'"

"Once you lose that aura it is hard to get it back," says John McEnroe, three-time men's singles champion here. "At the moment that aura is not there for Rafael Nadal. Players feel it and can feed off it."

Can Nadal get it back?

Can the clock be turned back?

History has begun to repeat itself for Nadal, the man who once reshaped it to his will.

Each of these four defeats in the past four years has come the same way - against a big hitter who went for every shot without fear and made enough of them.

Brown's performance was a throwback to McEnroe's own era, his victory founded on a classical grass-court game that saw him win a remarkable 71 of 99 serve-volley points.

A year ago Nadal lost the first set to Kyrgios, won the second and looked to be ready to re-establish the old order, only to be trampled in the remaining two instead. So it was again against Brown.

"Rafa has definitely got at least five more years in the game if he wants that," says Henman.

"His game is much more physically demanding than Federer's, which might make it harder to play as long as he does. But he still has the passion, which is hugely important. We saw his enthusiasm out there on Centre Court. He still wants it, which is a great sign."

Others are less optimistic, seeing instead a game that is running away from a player even as his own speed of movement and reaction are in decline.

"The grass has changed," says Marion Bartoli, 2013 ladies' champion here. "The way the ball bounces on the grass has changed, and it really does not favour Rafa.

"The top-spin he plays really doesn't help him because the ball is just sitting perfectly for players to pounce. And since it is harder to defend on grass, he is not having the long rallies like on clay."

Had those watching the then-24-year-old Nadal's demolition of Berdych in the 2010 Wimbledon final been told that he may never win another, we would have assumed career-ending injury or the rise of an unstoppable opponent.

Djokovic's own outstanding ascent would deny Nadal in the following year's final. Since then he has never come remotely close. Even to those relishing Brown's improbable fairytale the bittersweet taste cannot be ignored.

What's on - and when? | |

|---|---|

- Published2 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published8 November 2016

- Published9 November 2016

- Published17 June 2019