Rio 2016: Alistair and Jonny Brownlee - inside their minds

- Published

Alistair Brownlee is two years and seven days older than his brother

The Brownlees: An Olympic Story |

|---|

The triathlon triumphs of the Brownlee brothers have been impossible to miss - Alistair was Olympic champion at London 2012, twice the world champion, the European champion, Commonwealth gold medallist; Jonny won Olympic bronze, world champion in the same year, Commonwealth silver.

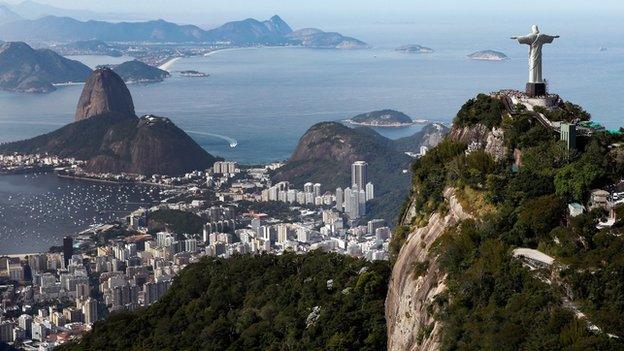

Now, with the Rio Olympics closing in fast, a new BBC documentary explores how they do it - what sets them apart, what drives them on, what hurts and what works, and how a pair of brothers can compete with each other every day, yet stay so close.

On chance

It's one thing being born within easy riding distance of the empty roads and climbs of the Yorkshire Dales. It's quite another going to a secondary school where keen runners were allowed to leave the school gates at lunchtime to train, and then join the front of the lunch queue when they got back.

Alistair: "You could literally roam wherever you want. That sense of adventure, being able to leave school, and that sense of freedom, is something that really inspired me. I'm sure I'd have failed at everything without that."

The brothers attended Bradford Grammar School and the University of Leeds

Jonny: "Triangle Bike Shop was one of those things that was just pure fluke. We were in Horsforth, which is not a big town. It happened to have one of the first triathlon shops in the north of England, when very few people knew what triathlon was.

"Adam Nevins, who ran it, was great. He gave us the kit - when we'd bring our bikes in with all sorts of bits broken, he would stop his work and fix them for us. But the other far more important side is the time he put in to show us the endless routes around the Dales, and in giving us this philosophy: to enjoy training, to not really worry too much about numbers in those days, to just go out and ride."

On pain

Three training sessions a day. Physical discomfort in each. In every race, a burning in legs and lungs that would make any ordinary person throw in in the towel.

Alistair: "It would seem quite strange to a lot of people, that you could actually enjoy physically hurting yourself. It doesn't seem to make sense.

"I don't know where it comes from. I think in some ways that it's not quite escapism, but everyone has a state of mind, or something that they enjoy doing or something that takes them away from everyone else, and maybe that's been it for me."

On competitiveness

Two of the best triathletes in the world, not just in the same training group but in the same family. Competing together in every training session, battling for the same medals and Olympic glory.

The brothers won gold in the mixed team relay at the Glasgow Commonwealth Games in 2014

Jonny: "It has spilled over, definitely. We've been doing races that are low key and supposed to be fun. In 2012, we raced the Yorkshire cross country championships, and although we were first and second, we'd had a busy week and should just have been running together.

"Instead, with a kilometre to go, we were absolutely maxing out. It was a couple of weeks later that Alistair tore his Achilles. That race probably went a long way to doing that.

"If both of us had backed off for the last 10-15 seconds, which we could have easily done, then we would have been fine. We should really have thought, 'It's January 2012, the Olympics are eight months away, why are we racing each other?'"

On winning

In 2012, Alistair won Olympic gold. Since then, a succession of injuries have disrupted his chances of adding to his world titles. With Rio closing fast, he is looking to be the first male triathlete in history to retain an Olympic crown.

Jonny Brownlee: I need to believe I can beat Alistair

Alistair: "Winning feels very different depending on the event, your state of mind and how competitive it is.

"People say, 'How do you cope with the pressure of the Olympics?' Really, it's just been the same - I've stood on thousands of start lines, and it's a slow progression from the start line of a Leeds school cross country race to the Olympic Games. I wanted to win the Yorkshire Cross Country Championships when I was 12 just as much as I wanted to win the Olympics when I was 24.

"I've had some great experiences, where I've got everything out of myself that day, everyone was competitive. That's fantastic - the Olympics was like that for me.

"I've had other days where I've thought 'Yeah, I could have done things a lot better there. I didn't do that well'.

"And then I've had races where I've gone into it thinking 'I'm going to really struggle to win this, I'm only going to win this either by sheer guts or by being a bit clever about it', and I've pulled it off. They're very, very satisfying races."

On losing

Every athlete has to lose. But is the pleasure you get from winning more intense than the disappointment of losing?

Alistair: "Definitely. It's not like I cross the finish line and I'm disappointed that I've lost - I'm disappointed sometimes when I don't feel like I can race to the best of my ability, and I don't feel kind of satisfied that way. But in terms of actually losing, the times that Jonny's beaten me or Javier Gomez has beaten me, if I feel like I've had a good race then I'm actually pretty happy with that.

"But it's also a bit dangerous as well, because I don't like this attitude of, 'I had a bad race but it's a learning experience.' That's a very convenient excuse for a lot of people, why it's a good reason to have bad performances when it's not."

Jonny: "The first reaction is, 'Wow!' if I've won or had a great race, and the next reaction is definitely a bit, 'That was a bit weird - I'm upsetting the norm, I shouldn't be beating Alistair.' And it's something that I need to get over.

"I know I need to go in to races with confidence, because if you go into races and kind of expect Alistair to win, you are already beaten. It means those days when we're equally as good as each other, he's more likely to edge it because he expects to win.

"Hopefully it's something that I've been able to change over the last few years, to be able to expect to beat Alistair. Or maybe not expect to, but not to think of it as something completely crazy if I do."

Jonny was victorious in Stockholm in 2014, with Alistair in second place

On the buzz

Why push yourself through so much physical and mental torment? Is there still the same endorphin rush that amateur runners and cyclists feel after a training session or inconsequential local race?

Alistair: "I think on some level when you're an elite endurance athlete, that buzz is what you do it for, day in day out. It's probably an addiction to some extent. You don't feel quite right without it.

"It's a bit unfortunate in that you're starting off and you're running for half-an-hour and you get that buzz, and yet it gets to a point where if you haven't done six hours of training in a day you don't get it at all.

"You get the bigger buzz after racing as well, because it's physically testing and there's the psychological aspect of it and winning. But it's something that really interests me - I've asked quite a lot of old and retired athletes, does that kick ever go away, or do you still keep needing to feed that addiction, even when you're 60 or 70 years old? Do you still need to go out and give yourself a bit of a kicking to feel happy?"

On injury

Repeated ankle problems for Alistair, a stress fracture in 2015 for Jonny just as he was hitting top form. How to handle your job and your favourite hobby both being taken away from you?

Jonny: "I thought I'd be an awful injured athlete. I thought it would drive me crazy not being able to do anything, but I'm actually very good at changing my goal to a different one.

"Instead of focusing my training, I was trying to be the best kind of injured athlete I could possibly be. That involved being the best use of crutches in the world - my left leg didn't touch the ground for four weeks.

"Straight away, I got on the phone to the nutritionist to ask how I could heal it. What were the best possible things I could eat? I got told all the usual - protein shakes, eat lots of cherries, that kind of thing. I made myself the best sort of nutrition plan in the world. I don't think I could have done a better job of giving it the best possible healing."

Alistair won gold at London 2012, with Jonny third, and Spain's Javier Gomez second

On rivalries

While the Brownlees have been injured or chasing other prizes, Spain's Javier Gomez, external has claimed world title after world title. Going into Rio, it's Gomez and his compatriot Mario Mola who pose the biggest threat once again.

Alistair: "The times I've spent with Gomez, he's been very cordial, but it's not like we're best friends and we go out for a beer with each other. I don't think while your rivalry is that strong in sport, you're going to be that friendly, I think that's just the way it is, however many things you've got in common - you've got no chance.

"I'd much prefer Jonny to beat me than Gomez! That's the crux of it. At the end of the day when you're stood on the start line I want to beat both of them, but I'm actually probably a bit more worried about Jonny on his day than I am about Gomez.

"Jonny's got the capabilities to have a really good day, and I'm not quite sure with Gomez. He surprises people sometimes as well, so who knows. Come the Olympics, I'd much prefer Jonny to beat me than Gomez."

On each other

They no longer live in the same house, as they did in the build-up to London 2012. But no more than a mile of road or footpath separates them, and the relationship is, if anything, even stronger than it was then.

Jonny: "In Alistair's head, his way is definitely always the right way. And if it's not the right way then he'll just argue that it is the right way, whatever. And then he'll change the opinions to what he wants and then say what he was arguing was that way anyway.

"If he were a film, it would be 'Alistair's Movie. The Best Movie Ever. By Alistair Brownlee, starring Alistair Brownlee'. And he would convince everyone that it is the best movie, even if it's not."

Alistair: "Jonny is basically that guy out of One Foot In The Grave, the miserable old man. And he acts like that a lot of the time. He hates it when I call him Victor. But that TV programme was written about him before his time.

"If he were a film, I think it would have to be some kind of spoof comedy about how very mundane things annoyed him terribly. So the tagline would have to be something along the lines of, 'The day the world ended because the postman was late…'"

On themselves

Does an Olympic gold make you happy? Sometimes. For a while. And then?

Alistair: "I think whether I'm happy with or not, I've made my decision already. I might have four or five years of being the best in the world and then pay for it later in life.

Jonny Brownlee finished 31 seconds behind his brother at London 2012

"I made a decision to be as good as I possibly can be, and there are negatives to that choice. The big one being it's a complete life change - you might be wanting to do other things, like in education, or a career or whatever.

"But it's not necessarily something that's bad. You make the decision for a positive reason - you want to be as good as you can be. It's not a drawback, it's the choice."

Jonny: "I think I am more of a team player. I like being around people more than Alistair, I like kind of working off people, and I like to think I'm quite good at that relationship.

"Being with people - getting the best out of people, so that includes training partners so when you're training with them or when you're racing with them, working together - I'm better at. And I'm a lot better at listening to other people, and involving their ideas, whereas Alistair is a bit more, 'It's my way'."

On motivation

How to keep going through those three training sessions, day after day? How to keep going when you have already won the greatest prize your sport has to offer?

Alistair: "I've got no idea. I've always been a bit scared of losing that ability to push myself.

"But it's been absolutely amazing - every time I've had an injury and it's got to that stage, the first time I've had the chance to push myself, not only do I have the experience afterwards where everyone thinks, 'Yeah, it's fantastic - I've gone hard', I actually get a few moments in and I think 'I just love being in pain!'

"I actually love this. I thrive off pushing myself, not only if it's a competitive situation, trying to hang on to someone, but also just on my own, being able to push myself and hurt.

"I've got no idea where that's come from, I think it's just years and years of just doing it may be and enjoying doing it. Although I think my dad would tell you, even the first time he saw me doing cross country as a six-year-old, I went red in the face and looked like I was about to die. So maybe I had it even then."

Jonny: "Alistair is a little bit more motivated by being outside and by exploring, which I really do as well, but may be not so much. I am definitely motivated by setting a goal and going for it.

Alistair Brownlee: I'd prefer Jonny to beat me in Rio

"I've always been like that as a kid. I remember growing up and wanting to qualify for the Yorkshire cross country team, so I told myself over Christmas I was going to run every day. On Christmas Day, we were travelling to my uncle's house and I would say 'Right, I'm going to get up and go for a run'. So I got up early, opened my presents really quickly and went out for a run, because I wanted to get my run in, because I'd set myself that goal."

On Rio

Less than 100 days to go. Four years that have flown past. Gold and bronze then. And now?

Jonny: "In London, when we turned up and went through security, everyone else had to get their water bottles out of their bag, their Allen keys to go through airport security. Whereas the army boys saw we were British, and said, 'Don't worry lads, you go straight through...'

"The other side of it is to race in London. We caught a train down, went to Leeds station, sat out in some coffee shop until our train turned up in all our kit, caught the train down to London, like nothing was happening - normal commuters just walking past us like a normal day.

"That was when we had that home advantage - and the home crowd was everyone cheering for us. But that brought with it a lot of pressure, a lot of expectation and a lot of things leading up in to the race.

"It's quite nice to have something completely different, because London's done now as an athlete - I've had that experience, and let's go on and have a completely different experience in Rio."

Alistair: "I like to think I am still the best one-off racer, but I'm not sure. It's been tested in the last year or so, but I think you've got to tell yourself that.

"If I can be in the shape I was in in London, I can be in position to win any kind of triathlon. And I'd like to think I can be better than that, so you've just got to keep telling yourself that and train towards it."

On the future

Someone close to the Brownlee brothers once once told me that when they had finished triathlon, one was going to be successful and one was going to be happy. Can they guess which one they were?

Alistair: "People would probably say that I would be successful, because I'd be driven and because I'd want to do something else. But even I don't know that myself.

"Some days I wake up and think actually I'd love to do something else, in a completely different career, to prove I could be successful at something else, just to myself, out of interest. Then other days I wake up and think, 'Sod it - nah, I can just live a nice life where I can bike out to a cafe every day and not worry too much…'"

Jonny: "I think I'll be the happy one. Because when I finish triathlon I'll do what I want to do, whether it's teaching or still involved in sport, and that'll keep me happy whereas Alistair will want to go and do the best that he wants to be. If that leads to financial gain or unhappiness or whatever, I don't know. But he'll try his best at it."

- Attribution

- Published11 May 2016

- Published9 May 2016

- Published19 July 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published15 September 2016

- Published21 September 2018