Billy Boston: Welsh rugby legend who never played at the Arms Park

- Published

Billy Boston (centre) collects his award from dual code international Jonathan Davies

Once upon a time long ago, two boys born in the same city in the same year grew up as neighbours - one at number four Angelina Street in the old Tiger Bay area of Cardiff, the other at number seven.

They made it together into the same Cardiff schoolboy rugby team of the late 1940s and then they went their separate ways.

The boy at number four - the late Joe Erskine - became heavyweight champion of Britain and the Empire, a stylist whose ring career included victories over three world title contenders - Willie Pastrano, Henry Cooper, George Chuvalo.

And what became of the boy at number seven Angelina Street? Well, how long have you got because we are talking about the greatest try-scorer in rugby history - union and league - 571 touchdowns in 562 matches.

His name is Billy Boston.

His mother, Nellie, was Cardiff-Irish, his father, John all five feet four inches of him, was a merchant seaman from Sierra Leone. They had 11 children and Billy came smack in the middle.

Rugby League legend Billy Boston wins lifetime achievement award

He went to South Church Street School in Butetown and by the time he left his ambition was to play rugby for Cardiff at the Arms Park.

He started with the multi-national Cardiff International Athletic Club - the CIACS - in the city's docklands and played for Wales in three boys clubs' internationals and in three more at Youth level.

Everyone had heard of him but still nobody at the Arms Park asked him along.

Neath did, and they showed their gratitude, according to Billy, by slipping him a white five pound note under the table after every match.

A price worth paying

Then he went to the north of England to do his National Service and all the Rugby League clubs could hardly believe their luck. Wigan moved quickest of all.

They sent chairman Joe Taylor and vice-chairman Billy Gore to Angelina Street on Friday, 13 March 1953.

Billy was home on leave. The Wigan bounty hunters offered him £1,000, a fortune 63 years ago.

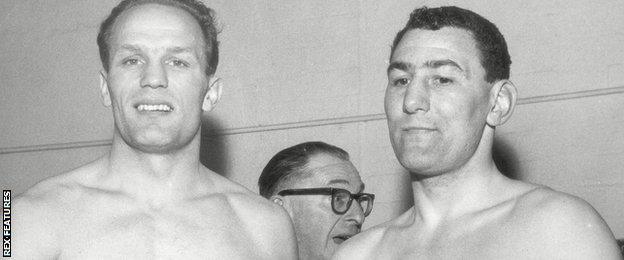

Boxing champion Joe Erskine (right), pictured with Henry Cooper before one of their five fights, was a boyhood neighbour of Billy Boston

When Mrs Boston rejected the offer, Taylor and Gore upped the offer to £1,500.

For effect they spread the white fivers all over the table. Billy had never seen so much money in all his life but he didn't want to go.

At this point he and his mother asked to be excused for a moment.

Nellie took charge as mother-cum-agent.

"Don't worry son, I'll get rid of them for you. I'll ask them for so much that they'll go home."

So when they went back into the little front room, Nellie said: "Right pay him £3,000 and he'll sign."

Billy thought to himself: "That's a really smart way of getting rid of them. Three grand? Nobody's worth that much."

What they had no way of knowing was that before leaving for Cardiff, the Wigan delegation had drawn £3,000 out of the bank.

They put their heads together for less than a minute and said: "OK, Mrs Boston we will pay you three thousand pounds. All Billy has to do is sign this contract"

Billy Boston (with ball) scored two of Wigan's tries in the 1960 Rugby League Championship final against Wakefield Trinity

Boston didn't want to sign it and his mother had to remind him - Wigan had come up with the money, now they had to keep their word.

He signed and years later he told me that he cried that night, that he couldn't sleep. His dream of playing for Cardiff had gone, never mind playing for Wales.

But that was Cardiff's fault. Their complete failure to show any interest in the player beggared belief.

Nobody could be sure why they ignored him, but at about the same time they also ignored other black players from Butetown, like Johnny Freeman and Colin Dixon who both made it big in League.

And that left Boston with one possible explanation - that they didn't like the colour of his skin.

Here was a wing who at 18 had all the tricks of his trade. He could beat opponents any and every way - body swerve, side-step, hand-off or just sheer pace because most didn't see him for dust.

The late Great Britain test captain Vince Karalius, one of the hardest men to play the game, described Boston 'probably the most magnetic crowd puller in the history of British Rugby League.'

Another called him the Oscar Peterson of 50s rugby, a striking comparison with the vistuoso jazz pianist given that Billy led most opponents a merry dance.

On this day: Britain win 1960 World Cup

But he wasn't just a great player. The fans loved him for that, of course. But they loved him too for his humility.

The late Phil Melling, Emeritus Professor of American Literature at Swansea University, put it best. Billy was a showman but never a show off.

In 15 years at Wigan until the late 1960s, he left records that will never be broken, not least 478 tries in 487 matches for the club.

And even when he was winning Challenge Cup finals at Wembley, with Billy it was all about the team, never about himself.

They loved him so much in Wigan that they stumped up £90,000 to put a bronze statue of him up in the town.

Maybe one day Cardiff will do the same because, when all's said and done, Billy is a Cardiff kid at heart.