Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan: When Olympic figure skating met whodunnit

- Published

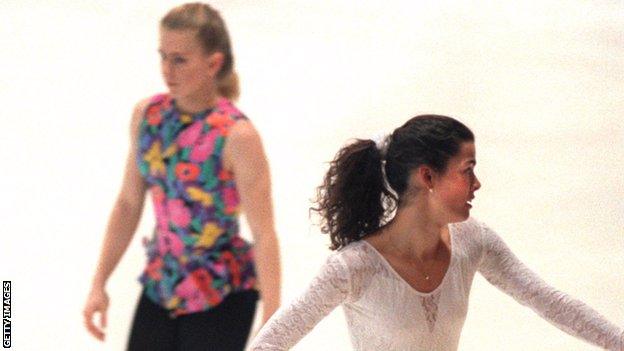

In the build-up to the 1994 Winter Olympics, Nancy Kerrigan (right) was attacked by a man hired by the husband and bodyguard of rival Tonya Harding (left)

It was a black-and-white story for a glitzy sport in a gaudy era: Tonya Harding the villain, Nancy Kerrigan the victim, Olympic figure skating mixed with whodunnit and farce and tragedy, a vast global audience relishing each macabre twist and turn.

Almost a quarter of a century on, the story of US skater Harding and the attempted nobbling of her rival Kerrigan is back to stalk the Olympian ideals once again. A new biopic - I, Tonya - arrives in British cinemas this week. The farce and tragedy is still there. What's changed is the certainty.

Harding was always portrayed as the stonewashed-denim bad girl from the wrong side of the rink, Kerrigan the clean-cut kid with the wholesome backstory. One skated to heavy metal and danced in home-made costumes. The other did Campbell's soup commercials.

Had their rivalry stayed on the ice, you might never have heard of them. But in the build-up to the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, preparing for the US National Championships, Kerrigan was attacked, external as she finished training. Harding's ex-husband and her bodyguard had hired a third man to break her leg, hoping to ruin her Olympic hopes and thus dramatically boost Harding's.

In Fargoesque fashion, it went wrong. The assailant, a man named Shane Stant, initially failed to recognise Kerrigan, having to ask a spectator to point her out. When he did strike her, with a telescopic baton, he missed her knee and managed only to inflict a bad bruise. Attempting to make a stealth escape, he panicked so badly he decided to headbutt his way through a glass fire-escape door.

Kerrigan - famously filmed in the immediate aftermath repeatedly wailing the word "why?" - recovered rapidly enough to make Olympic selection. Harding won the nationals and went to Lillehammer too, accompanied - as a result - by a media and moral frenzy that would threaten to sweep both away.

Those are the facts. What the film attempts to reassess is our reaction to them: how much Harding knew of the plot, how much she was to blame; if she ever stood a chance, as a blue-collar girl wearing skimpy pink chiffon; whether it was actually her, after a childhood and marriage steeped in alleged abuse, who was the victim as much as Kerrigan ever could be.

"There's no such thing as truth," says Harding, played with foul-mouthed relish by Margot Robbie, at one point. Which might seem rather 2018 for a drama set 24 years ago, but reflects too the conflicting stories told by Harding, her then husband Jeff Gillooly, bodyguard Shawn Eckhardt and Harding's mother LaVona.

Gillooly spent time in prison for his part in the crime. So too did Stant, Eckhardt, and Stant's getaway driver Derrick Smith. Harding pleaded guilty to hindering the prosecution, which meant she admitted she knew the identity of those behind the attack, but not until after it happened., external For that she received three years' probation, a $100,000 fine and 500 hours of community service.

Speculation filled the gaps and much more besides. Surely Harding knew more about it, went the cynical line. And that was how she was treated at those Olympics: as not just an unwitting accomplice, but as an instigator too.

A tearful Harding finished eighth at the 1994 Olympics, six places adrift of Kerrigan

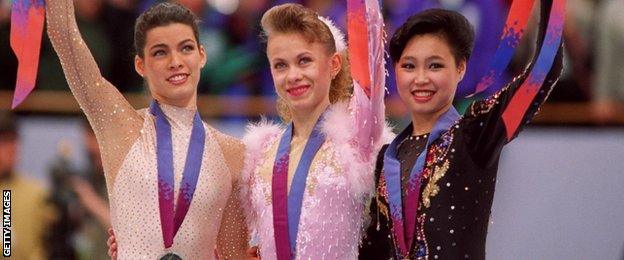

There would be no happy ending in Norway. Harding, struggling with a broken lace on her boot, finished that Olympic final in eighth. Kerrigan went better with silver but looked as happy with that as with a fall, Oksana Baiul from Ukraine sneaking up unseen on the rails for gold.

In the aftermath, Harding was banned for life by the US Figure Skating Association. At the time that seemed draconian; the film suggests it may have had as much to do with her background and image as the alleged crime.

Rewatching that Olympic final brings other subtleties back the fore. It is easy to forget what a great skater Harding was, athletic where Kerrigan was balletic, the first American woman to land a triple Axel in competition.

If her aesthetic is uncomplicated - a maroon outfit for the free skate in Lillehammer to Kerrigan's puritan white, a song from Jurassic Park her soundtrack - her performance is all speed and height and spins.

Film and television often struggle to accurately capture either the physicality of sport or its capacity for impossible plots; fiction takes you to a set resolution, sport can take you anywhere. I, Tonya reminds you of both.

Then there is the scene with Harding in the toilet just before that showdown, alternating between tears and an awful fixed grin, her heavy make-up both warpaint and an inadvertent nod to her status as pantomime villain. In that moment you get an acute sense of the pressures an Olympic final creates, of the oft-described feeling of spending your whole life working towards this moment, yet when it arrives being desperate for it to pass.

Harding is held up to exemplify another darker element of the Olympic dream: the lengths obsessive athletes will go to when they're put under pressure. The film makes it clear she is an unreliable witness. It also tries to explain why.

"People tell themselves what they need to tell themselves in order to be able to live with themselves," screenwriter Steven Rogers told BBC Sport.

"Everybody has their own truth. Jeff says he never hit Tonya, yet there are police reports. Tonya says nothing is her fault, and Shaun the bodyguard tells everyone he works for Third World dictators and has hitmen at his disposal, and he's doing that because he's 400 pounds and lives in his parents' basement and he was lonesome."

Harding's fall was supposed to tarnish the sport. Instead it was arguably part of a strange golden period, bookended by the perfection of Torvill and Dean and Katarina Witt before, and precocious brilliance of Tara Lipinski and Michelle Kwan afterwards.

Kerrigan (left) won silver in Lillehammer, with Oksana Baiul (middle) taking gold

That 1994 women's final, shown on a tape delay to make up for the time difference, broke television audience records in the US. Only two Super Bowls had ever drawn more viewers to a sporting event. As any boxing promoter will tell you, enmity and scandal sells tickets.

The ripples spread deep into American culture. After the scandal, Harding was variously embroiled in a sex-tape dispute with Gillooly; appeared alongside OJ Simpson witness Kato Kaelin in 'The Weakest Link: 15 Minutes of Fame Edition'; had a short pro boxing career, once fighting on a Mike Tyson undercard; worked as a welder, till girl and decorator; and was referenced in songs by artists as diverse as hip-hop stars Lil' Kim and Lil Wayne, singer-songwriters Sufjan Stevens and Loudon Wainwright III, and pop-punk band Fall Out Boy.

In the revisionist version of her story that the film's success has encouraged, she has even been compared to Monica Lewinsky, another frequently mocked 1990s woman ultimately exploited by others. Typically, Harding disputes the affinity to someone born into comfort and employed at the White House.

She is unlikely ever to be forgiven, even though she is now a different woman to that 23-year-old girl, with a different husband, a new surname and no desire to go back to skating.

Maybe she brought much of it on herself. But it is a long time to live in the shadow of one event, unprecedented though it was.

- Published22 February 2018

- Published24 February 2018

- Published8 February 2018