How Torvill and Dean chose heart over head and changed a sport

- Published

Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the latest in the series here.

Stepping off the early-morning train from West Germany, Christopher Dean and Jayne Torvill were unlikely-looking revolutionaries.

Dean, 25, wore a stiff shirt, cravat, argyle jumper and pinstripe team blazer. Next to him, Torvill, 26, sported a fur-trimmed coat, matching hat, silk scarf and a shy smile. Not on display, but somewhere back in Nottingham, were their recently awarded MBEs.

In front of them, as they posed obligingly on the platform of Sarajevo station, stood a clutch of photographers snapping away.

Nine days hence lay a risky, risque gamble: a shot at Olympic ice dance gold which depended on a routine that bent the rules and challenged convention - a free dance number that could burn up like chiffon to a spark.

Torvill and Dean could easily have played it safe.

Instead they played with fire.

Torvill and Dean arrived at the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo on the back of three successive world title victories

"We felt strongly about what we were doing," says Dean, 40 years on. "It was only other people who felt it was a gamble."

"We always had to be one step ahead with where our ideas were creatively," adds Torvill. "We tried to tell a story - so it had a meaning."

But 1984 was a time when narratives competed to crush one another.

Cold War nerves were frayed thin with American and Soviet warheads bristling in silos, amid false alarms and dangerously realistic military exercises.

At home, there was also conflict.

A few weeks after Torvill and Dean's arrival in Sarajevo, the miners' strike - a year-long dispute that divided families, communities and their home county - began.

On the rink, there was no escape from politics either; a schism ran through the ice.

There were the traditionalists, who believed in respecting ice dancing's ballroom roots. They prioritised a mix of decorum and control - a chilled accuracy, efficiency and propriety in the skaters' movements.

A new wave was breaking ground though - a looser, dramatic, romantic style was emerging, one that thrilled crowds, even if it put off old-school judges.

The two approaches were different. And in a subjectively scored sport, where medals were decided by the numbers dished out by judges, being too different made you vulnerable.

Initially Torvill and Dean had leaned towards a conservative approach.

They were coming into the Olympics on the back of a hat-trick of world title wins. There was little to prove, and so much to risk.

This, as far as they knew, would be their final shot on the greatest stage, as they were bound for the professional circuit, barring them from future Olympics under the rules of the time.

A throw-back 1930s razzmatazz showtune from the musical 42nd Street was planned. It would show off their skills, and satisfy both judges who preferred a classical routine and those who favoured the more colourful.

But would it satisfy Torvill and Dean themselves?

Over a west London dinner party, after rifling through cassette tapes in search of a tune and a theme, they decided ultimately it wouldn't.

An altogether more daring crescendo to their Olympic careers was called for.

In the basement of their hosts' flat, pleated silk outfits were dip-dyed purple. An arranger was recruited to cut 15 minutes of music by two-thirds, while preserving its shimmering heart. And Torvill and Dean retreated to Oberstdorf in the Bavarian Alps to work on something new away from prying eyes.

"These days, with camera phones and social media, it is very hard to keep things under wraps, but nobody really knew what we were doing," says Dean. "We believed in what we were doing, as opposed to listening to those saying that it wasn't right for Olympic year, that we should do something safer."

"We wanted to do something that we had never done and that had never been seen before," adds Torvill.

Certainly nothing like Bolero had been done before. Arguably nothing has matched it since.

The famous start to Torvill and Dean's Bolero routine was choreographed to make up for 18 seconds of excess musical accompaniment

Torvil and Dean's free-dance routine in Sarajevo on 14 February 1984 started with them kneeling on the ice facing each other.

They had no other option. Bolero, which builds from snake-charmer stealth to raging storm, couldn't quite be compressed into the allocated four minute 10 seconds allowed for a musical accompaniment.

But the pair spotted a loophole. The clock doesn't officially start until the first blade touches ice.

By kneeling, circling and swooping around each other for 18 excess seconds at the start, before standing and skating, their routine would still be legal.

Dean, during warm-up, would subtly rough up the ice in the required spot to avoid their knees, which gave far less traction than a sharpened blade, from sliding away under them.

Their routine ended with both back on the ice, lying prostrate, chests heaving.

In the minutes in between, they had transported the Sarajevo crowd, and a UK television audience of 23 million to new heights.

Flowers rained down on the ice. A full house of perfect artistic impression marks lit up the scoreboard.

"Tonight we reached the pinnacle. I don't remember the performance at all. It just happened," Dean said at the time.

Any fears over their music, staging or steps had vaporised. An unnamed rival coach had a theory.

They told the New York Times that only Torvill and Dean's magic was powerful enough to close the sport's rifts.

"Perhaps," they said, "the judges have to accept Torvill and Dean because they are so darn good.

"But they don't want ice dancing to change radically, so they are ready to punish anyone else who tries to be different."

Everything had changed for Torvill and Dean themselves, though.

Princess Anne toasted them with champagne in the stands. Her mother - Queen Elizabeth II - sent a signed telegram offering her congratulations on a performance that she "watched with great pleasure".

When they arrived back home, Torvill and Dean greeted fans from the back of an open-top truck, with a police escort. Later that year, Elton John would present them with the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award.

Torvill and Dean's success in Sarajevo propelled them to new levels of celebrity and scrutiny

Wherever they went, there was a question they were asked again and again: whether such romance on the ice could stop when they stepped off it? Whether, having suspended their disbelief, their fans really had to re-engage with a more mundane reality?

At one press conference, a journalist asked if they were to marry.

"Well, not this week," smiled Dean.

Torvill, reacting to the observation that the pair seemed more closely attached than other pairs, simply replied with a look across at her partner and an enigmatic "yes".

"We didn't consciously try and maintain an aura about it, but we didn't get into the conversation about it either," says Dean reflecting back on the speculation.

"We would keep it at arm's length, so I imagine people would speculate about it. People buy into what you are doing on the ice."

"If we are portraying two people in love and people believe that, then we are doing our job right," adds Torvill.

To make that romance touch millions is one thing. To make the illusion last over a decade is another.

Torvill and Dean await the start of their free dance at Lillehammer 1994, where they performed to Irving Berlin's Let's Face the Music and Dance

By 1994, rules had changed.

A relaxation of regulations meant Torvill and Dean, aged 36 and 35 respectively now, were free to return to attempt an extraordinary repeat.

Circumstances had changed too, however.

Torvill and Dean were now married - but, to the disappointment of many fans, to different people. They were also no longer the sport's golden couple, primed to take medals of a matching colour.

"I think some people felt we were coming back for the glory," says Dean.

"But we were really coming back to test ourselves for the challenge of it. It was a measure for us.

"Obviously there were countries and skaters who had been competing, poised for a medal, climbing up that tree who would feel put out."

The backstory was different. The context had changed. The tactics had to switch too.

After a raft of poor imitations in the wake of Torvill and Dean's Bolero routine, the skating authorities had become stricter about music choices and banned pairs from starting routines kneeling or lying on the ice.

"Because we had this reputation of bending the rules, so to speak, and we were coming back after 10 years as professionals, we wanted to really conform and not arrive in Lillehammer saying 'we can do this and get away with it'," adds Torvill.

They didn't dare try to replicate the audacity and authenticity of Bolero. Instead they opted for a routine to Let's Face the Music and Dance.

It was a gleeful, glitzy, intricate finale to their programme, full of showbiz sparkle and polish. It was different to Bolero - less raw, more cute - but, as the couple folded into each other's arms and the music gave way to cheers, it seemed it may well deliver the same result.

Flowers fell, the audience stood, the dream was alive, the fairytale went on.

Until it didn't. The technical merit marks arrived to shrieks of disgust from the crowd. Where, for Bolero, they had collected nine perfect sixes for artistic impression, they managed just one in Lillehammer.

The lead the British pair held going into the final round had been whipped from under them. Torvill, arms still cradling a clutch of bouquets, trudged backstage crestfallen. They would end with only bronze.

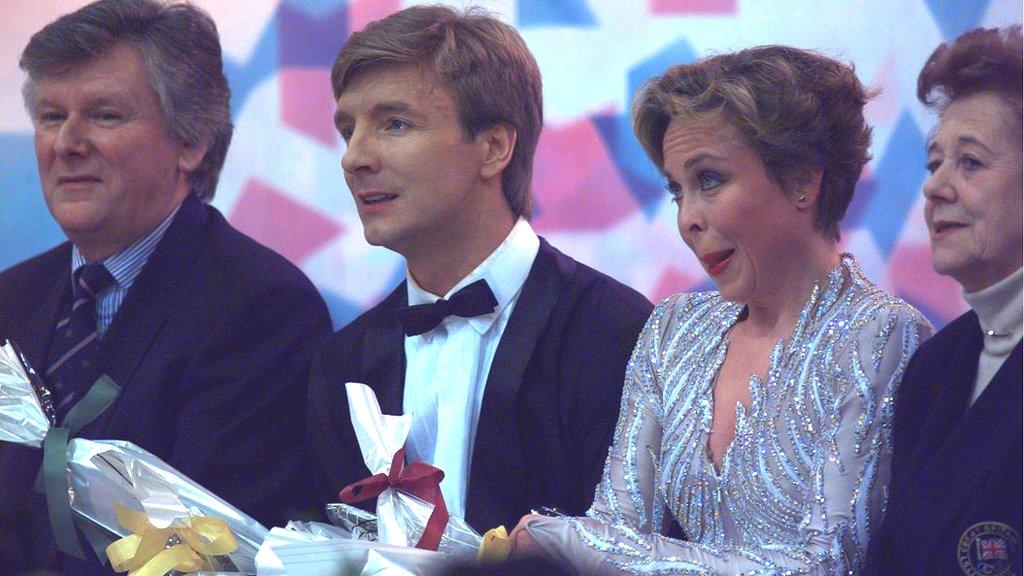

Torvill and Dean, with their coaches alongside them, watch their results come in for the final free dance section of the Lillehammer 1994 campaign

"We were a little surprised with the marks," said Dean at the time, leaving a pause before correcting himself.

"A lot surprised."

The papers back home were less restrained.

"Gold robbery" read one headline. The judges were accused of being either "biased" or "barmy" in one tabloid. A broadsheet said the credibility of ice dancing as a sport had been "destroyed"., external

The legality of a final lift was ultimately deemed the weak point in their routine.

With the benefit of another 30 years, Dean is more philosophical.

"We were taking advice," he says of the selection of their final free dance number. "It wasn't bad advice, but I don't know it was the right advice.

"As performers and artists, the passion and going with your heart is a really important thing."

Those following Torvill and Dean into the sport now are not short of direction.

The free dance comes with a weighty list of content that must be included in every performance. Each individual element is weighed, measured and assessed against a gold standard. Risk is mitigated. Surprises are minimised.

The standardisation leaves less room for the confusion and controversy of 1994, but also less room for something as compellingly original as 1984.

"You know you are getting this type of lift, that they have to do that spin and that footwork," explains Dean of the modern-day ice dance scene.

"It is about both the quantity and quality you put into it - but a lot of it is quantity.

"The sport has moved forward in its athleticism, the standard of the skating is amazing, but it does mean there is a bit of a sameness."

Torvill and Dean's own last dance is almost here. Tickets have gone on sale for a 28-date farewell tour, which will culminate in Glasgow on 11 May 2025.

It will be the end of their 50-year skating partnership and Bolero, and a chance to suspend disbelief once again will surely be the centrepiece.

Squeezed out of sport it may have been, but their romance is still squeezing spectators into seats.

Torvill and Dean have recreated their Bolero routine hundreds of times all around the world since, but the 1984 Olympic gold-winning rendition remains unsurpassed

Watch: Torvill and Dean perform Bolero 40 years on