Bloody Sunday prosecution charges 'unlikely'

- Published

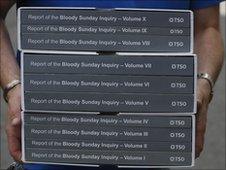

A man carries a copy of the long awaited Saville report

A lawyer representing British soldiers involved in the Bloody Sunday inquiry has insisted the report's findings did not open the door for prosecutions.

Stephen Pollard accused senior judge Lord Saville, who led the inquiry, of painting an unfair picture.

The British government apologised for the army's actions after the publication of the report which took 12 years to complete.

Mr Pollard said Lord Saville had "cherry picked" the evidence.

The report concluded that none of the victims were armed, that soldiers gave no warnings before opening fire and that the shootings were a "catastrophe" for Northern Ireland, leading to increased violence in subsequent years.

The 5,000-page report is based on evidence from 921 witnesses, 2,500 written statements and 60 volumes of written evidence.

None of the witnesses were granted blanket immunity from prosecution. However all witnesses were immune from prosecutions on the grounds of self incrimination.

This meant that the evidence given by a witness could not be used against them in any future legal proceedings.

However this does not rule out prosecutions against a witness in a broader sense, especially if the evidence against them is supplied by a third party or other witness.

Northern Ireland's Public Prosecution Service said it was considering whether to prosecute anyone, adding this decision would be taken "as expeditiously as possible" although it gave no date.

"The decision whether any individual will face prosecution arising out of the Saville Report is solely for the Public Prosecution Service acting independently in accordance with the Test for Prosecution," the PPS statement said.

"The Director of Public Prosecutions, together with the Chief Constable, will consider the report to determine the nature and extent of any police enquiries and investigations required to enable informed decisions to be taken.

"The undertaking given by the Attorney General in 1999 to witnesses who provided evidence to the Inquiry will also require to be considered," it continued.

BBC Northern Ireland's Paul McCauley, who was the only journalist to attend every day of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry said that any prosecutions against individuals would be unlikely.

"Given the Good Friday agreement, even if a soldier were to be prosecuted as a result of this, they would not spend a day in jail.

"That is not my opinion, that is a fact"

Some legal experts, however, said wriggle room remains for prosecutions and, more likely, civil lawsuits against retired soldiers, particularly as some of the them were found to have lied to the Saville Inquiry.

BBC legal affairs correspondent Clive Coleman said the decision whether or not to prosecute the soldiers would not be straightforward.

"There needed to be sufficient evidence to provide a reasonable prospect of conviction - not an easy test after 38 years.

"If any defendant believes that the passage of time makes a fair trial impossible, they could argue the prosecution was an abuse of process," our correspondent said.

"Any prosecutions would also need to be judged to be in the public interest."

Justified

When Mr Pollard, the lawyer representing British soldiers, was asked whether the report paved the way for the soldiers involved in Bloody Sunday to face criminal charges, he said: "No, it doesn't."

"He cherry picked the evidence," the lawyer said, referring to Lord Saville.

"I think Lord Saville felt under very considerable pressure after 12 years and 191 million pounds to give a report which gave very clear findings even where in truth the evidence didn't support them.

"What he has had to do is adopt the pieces of evidence that fit the theory and abandon those that don't."

Meanwhile the head of the British army, General David Richards, backed the apology by the British Prime Minister David Cameron.

"The report leaves me in no doubt that serious mistakes and failings by officers and soldiers on that terrible day led to the deaths of 13 civilians who did nothing that could have justified their shooting".

The inquiry was originally budgeted to cost £11m and report findings were expected by 2002.

The final bill was estimated at nearly 200 million pounds - making it the longest and most expensive inquiry in British legal history. Mr Cameron said Britain would never attempt anything like it again.