London helicopter crash: What are the rules for pilots?

- Published

The Agusta 109 that crashed should have been following a prescribed route

An Air Accidents Investigation Branch probe into Wednesday's helicopter crash in central London is already under way.

Investigators are expected to focus on weather conditions, and whether the pilot of the Agusta 109 followed correct procedures.

But what are the rules governing helicopter flights over one of the most highly populated areas of the UK, and how risky do pilots find it?

Many Londoners might be surprised at the sheer volume of helicopters flying over their city - the Civil Aviation Authority recorded 16,374 flights last year, between January and October.

Aviation expert Chris Yates told the BBC: "London airspace is extremely busy. There is Heathrow to the west and London City to the east.

"As well as that, you have helicopter flights bringing business people into the city, police helicopters and Medevac flights to and from hospitals."

The Civil Aviation Authority has strict rules , externalgoverning private helicopter flights.

It has established the London Control Zone, a portion of controlled airspace that extends from ground level to an altitude of 2,500 feet, within a 10-mile area of Heathrow airport.

Any aircraft - including helicopters - wishing to fly within this area must have air traffic control (ATC) clearance and obey the instructions of air traffic controllers.

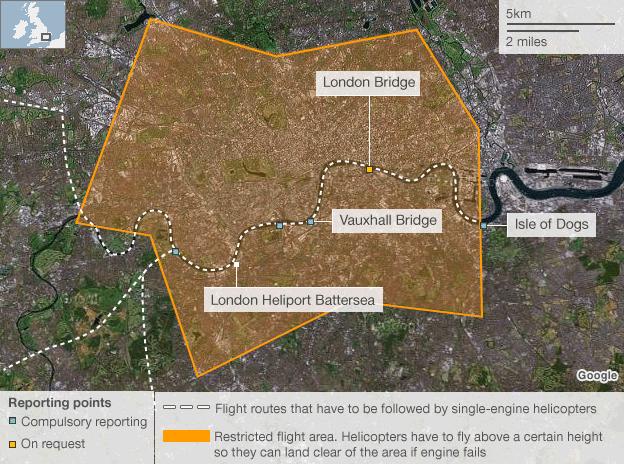

The helicopter that crashed was flying in the area of airspace labelled by the CAA as R160.

This is the largest restricted area covering central London, and CAA rules state pilots within it must not fly below a height that would enable them to land clear of that area in the event of engine failure.

And although pilots should follow air traffic controller advice on weather conditions, the final decision on whether to fly or not is down to them.

Peter Norton, chief executive of civilian helicopter trade organisation the British Helicopter Association, said: "Rules, routes and regulations concerning flying over London are well documented and familiar to pilots.

"It is a captain's decision on whether the conditions are fit for flying."

Helicopters should follow prescribed routes, which the CAA says provide "maximum safety by avoiding built-up areas as much as possible".

Pilots are expected to navigate with reference to ground features "with only limited ATC Radar assistance".

They are also expected to fly the "precise routes" depicted in the chart. "Corner cutting is to be avoided," stresses the CAA.

However, in order to avoid other aircraft, pilots are permitted to "temporarily deviate to the right of the route".

The Agusta 109 that crashed should have been following a prescribed route

The rules are stricter for single-engined helicopters, which should always follow the prescribed route. Within the R160 controlled area, for example, they must fly above the River Thames, which minimises the risk of crashing into a built-up area.

However, multi-engined aircraft - like the one that crashed - can be provided with ATC clearance to fly elsewhere in the London Control Zone.

Tall buildings

Tall buildings pose an obvious danger to low-flying aircraft, but here too there are strict rules to minimise pilots' risk.

CAA rules, external state any structure over 150 metres in height - what the CAA terms an "en-route obstacle" - must be fitted with "medium-intensity red lights" on the roof or top of the structure.

And under International Civil Aviation Organisation regulations, any structure over 45 metres tall on a flight path or near an aerodrome must be fitted with a medium-intensity aircraft warning light.

Similarly located structures less than 45 metres tall may require a low-intensity light.

The lights must also be fitted to any structures attached to the buildings - such as cranes.

However Civil Aviation Authority has confirmed the lights only need to be turned on a night - and not during bad weather in daylight hours. They say this is because the red warning lights aren't visible in fog or low cloud.

The rules say "night" is defined as 30 minutes after sunset until 30 minutes before sunrise.

Sunrise in London on the day of the crash was 7.57am - so the night period had ended around half an hour before the crash.

London's ever-changing skyline poses an obvious danger to pilots.

By law architects must inform the CAA if their buildings or construction cranes exceed a certain height.

That information results in a Notice to Airmen (Notam) warning which is posted to a day-by-day database, external pilots can consult before they fly.

Weather risk

Gary Slater, a helicopter pilot with more than 20 years experience, told the BBC: "You can gather that information that will tell you the crane has been erected, from what period to what period and what height it's at, so it's a known value that the crane is there."

The crane in Vauxhall thought to have been involved in Wednesday's crash appears on the database as a "high-rise jib crane (lit by night)", along with its co-ordinates and height - 770ft (234m) .

The strict rules help to reassure pilots flying over the UK's densely-populated capital that everything possible is being done to minimise risk.

The CAA stress the incident is the first case of a helicopter fatality in London since it started keeping records in 1976.

Its director of safety, Gretchen Haskins, told the BBC: "It's a rare event, but every accident is serious so we need to learn from it if we can. "There are strict rules on lighting on buildings and cranes.

A picture of nearby St George's Wharf Tower, showing the top shrouded in low cloud.

"But more important than that, there needs to be clear flight planning and use of the designated routes, adherence to air traffic control, and all of those things build up layers of safety to help prevent an accident."

Mr Slater said: "The principles in place for flying over London make it very very safe.

"It's very well controlled and there are some very good, long-established procedures."

But weather conditions remain the one unpredictable factor beyond any pilot's control.

Mr Slater said: "Flying in fog is one of the worst things in a helicopter, unfortunately.

"The Agusta 109 is capable of flying in those kind of conditions - it's a full IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) helicopter which allows you to fly by sole reference of the instruments, with autopilot engaged.

"Whether that's the case in this scenario is speculation at this point."

The key question that the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) team will want an answer to is: "Was visibility suitable for a helicopter flight over London?"

Battersea Heliport in south London has said that the pilot of the helicopter had requested to divert and land there due to bad weather.

And earlier, it is thought that the pilot had had to abandon his plan to land at Elstree in Hertfordshire due to fog.

Cloud in central London was low at the time of the accident, as evidenced by a picture of the tower close to the scene of the crash, which can be clearly seen to be shrouded in fog.

Forecasters say areas around London and to the north of the capital were shrouded in low cloud, down as low as 200ft, and areas of freezing fog.

The conditions were bad enough for London City Airport to announce flight delays.