Nepal quake: Why are some tremors so deadly?

- Published

Great efforts had been made in Nepal to improve resilience. Even so...

On 1 April, 2014, a Magnitude 8.2 earthquake rocked northern Chile. Six people died, 2,500 homes were damaged and 80,000 people were displaced. Just over one year later, a M7.8 earthquake strikes Nepal. Over 6,200 people (and counting) have been killed, entire towns and villages flattened and millions of people left homeless.

Chile's earthquake barely made the news, whilst Nepal's has brought complete and utter devastation. How did two such similar earthquakes have such disparate effects?

A huge part of the answer is, of course, building standards and wealth.

Since Chile's terrible M9.5 earthquake in 1960, where over 5,500 people died, the country has taken big steps in modernising its buildings, designing them to withstand the shaking produced by great earthquakes.

Meanwhile, in Nepal, few buildings were up to code, and many toppled when the earthquake struck.

But wealth and building codes don't tell the entire story: the geology is different, too.

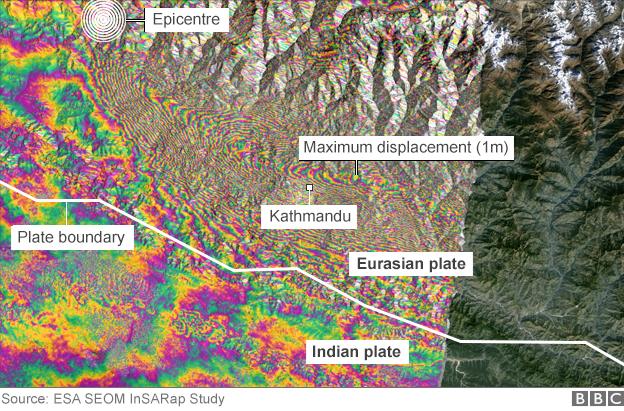

Nepal sits on a continental collision zone (India is smashing into Asia) and its earthquake fault is well disguised: most of the fault is buried deep underground and surface ruptures are quickly covered by muds washed down by monsoon rains and the dense jungle.

Furthermore, the speed of this continental collision (around 4.5cm every year) means that major quakes only hit Nepal every few decades. Chile's fault meanwhile is obvious - a whopping great trench where the Pacific Ocean floor dives underneath South America at a rate of nearly 10cm per year - with major earthquakes occurring every year, making earthquake-resilience a priority.

As continental collision zones go, Nepal's is at the simpler end of the spectrum and has been relatively well studied.

Indeed, geologists had identified Nepal's most vulnerable segment of fault just weeks before the recent deadly quake struck.

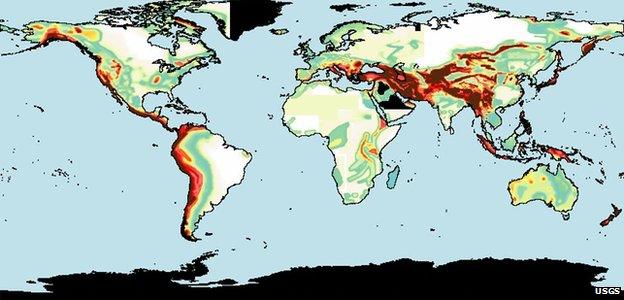

This US Geological Survey map shows where seismic hazards are greatest (red)

Other countries in continental collision zones are underlain by a nightmare of widely dispersed faults, splintering across thousands of kilometres of land.

All the way from the Mediterranean to Indonesia, lies a restless network of earthquake faults, created by the African, Arabian and Indian plates forging northwards into the Eurasian plate. Massive cities - including Istanbul, Tehran, Tabriz and Ashkhabad - are situated on some of the most dangerous land on Earth.

"Because continental faults are less confined, they rupture less frequently, with some faults only coming to life every few thousand years - well beyond human memory or recorded history," explains James Jackson, a geologist at Cambridge University, UK, external, who heads up Earthquakes Without Frontiers, external, a project to increase resilience to continental earthquakes.

Since 1900, earthquakes on continental faults have killed twice as many people as earthquakes on ocean-continent boundaries.

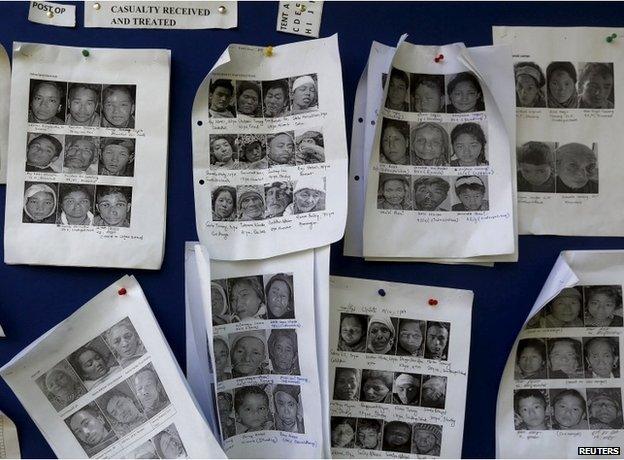

The Army hospital in Kathmandu posts pictures of survivors on a notice board

Over the last few years, Jackson and his colleagues have been tracking down these elusive continental faults in Iran, Kazakhstan and China.

Using high-resolution satellite images, they can spot anomalies in the landscape that hint at where the fault may lie.

Meanwhile, seismic reflections help to draw a picture of what lies underground. And back in the lab, the scientists study regular satellite snapshots of the Earth's surface to monitor how the planet's surface is deforming.

"We can see exactly where the Earth is being stretched apart or sheared, enabling us to map which parts of the Earth are under greatest strain," says Richard Walters from Leeds University, external, a member of the Earthquakes Without Frontiers team.

Inverted expenditure

In Nepal's case, much of this information was already available, and indeed a great deal of work had been done by local organisations (such as the National Society for Earthquake Technology, external) to prepare for the next big earthquake - training stonemasons, retrofitting schools and hospitals, educating people about earthquakes and stockpiling vital resources.

"It does appear that there has been much less loss of life than would have been expected from such a large earthquake (though the toll could still turn out to be in the tens of thousands) and there is evidence that the programmes of the Nepalese government and some of the non-profit agencies did save lives," says Philip England, a geologist at Oxford University, external, also part of the Earthquakes without Frontiers team.

If nothing else the devastating earthquake in Nepal will hopefully highlight to the international community how vital it is to build earthquake resilience.

"Five times more money is spent on a response [to an earthquake] than it is on helping people to prepare," Katie Peters, from the Overseas Development Institute, external in London, told Sky News earlier this week.

The first results from the EU's Sentinal 1 satellite show that last Saturday's earthquake in Nepal did not rupture the surface, suggesting that significant strain may still be stored on that segment of the fault, and that another large earthquake could hit in the coming decades.

"Appalling though this event is, it could have been far, far worse. Let's hope that this event is the trigger for a more positive outcome next time," says England.

Observations from Sentinel-1a are used to trace how the ground moved in the quake