How a cyber attack transformed Estonia

- Published

It all began when Estonian authorities decided to move a memorial to the Soviet Red Army to a position of less prominence in the capital, Tallinn

Cyber-attacks, information warfare, fake news - exactly 10 years ago Estonia was one of the first countries to come under attack from this modern form of hybrid warfare.

It is an event that still shapes the country today.

Head bowed, one fist clenched and wearing a World War Two Red Army uniform, the Bronze Soldier stands solemnly in a quiet corner of a cemetery on the edge of the Estonian capital Tallinn.

Flowers have been laid recently at his feet. It is a peaceful and dignified scene. But in April 2007 a row over this statue sparked the first known cyber-attack on an entire country.

The attack showed how easily a hostile state can exploit potential tensions within another society. But it has also helped make Estonia a cyber security hotshot today.

From outrage to outage

Unveiled by the Soviet authorities in 1947, the Bronze Soldier was originally called "Monument to the Liberators of Tallinn". For Russian speakers in Estonia he represents the USSR's victory over Nazism.

But for ethnic Estonians, Red Army soldiers were not liberators. They are seen as occupiers, and the Bronze Solider is a painful symbol of half a century of Soviet oppression.

In 2007 the Estonian government decided to move the Bronze Soldier from the centre of Tallinn to a military cemetery on the outskirts of the city.

The decision sparked outrage in Russian-language media and Russian speakers took to the streets. Protests were exacerbated by false Russian news reports claiming that the statue, and nearby Soviet war graves, were being destroyed.

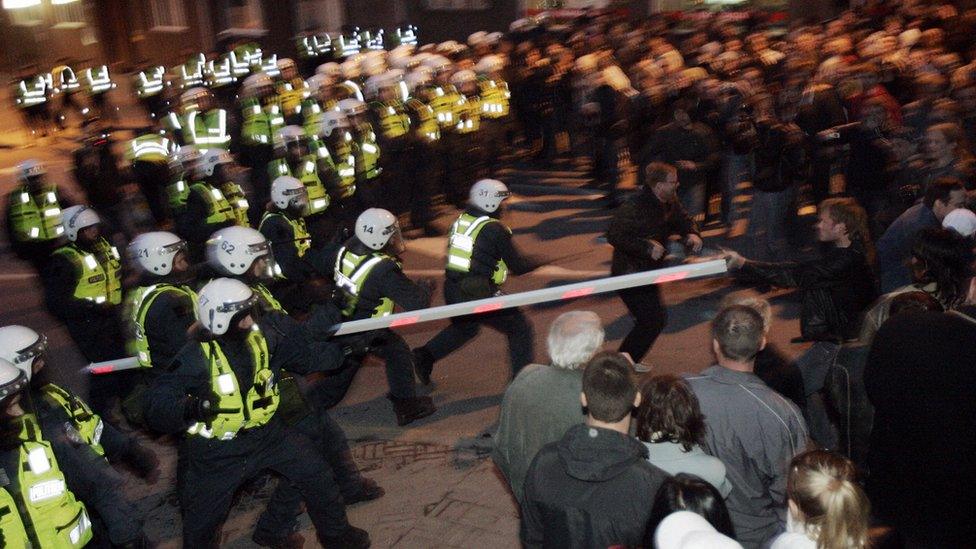

Russian speakers rose up on the streets in protest at the statue's move - and cyber attackers followed behind

On 26 April 2007 Tallinn erupted into two nights of riots and looting. 156 people were injured, one person died and 1,000 people were detained.

From 27 April, Estonia was also hit by major cyber-attacks which in some cases lasted weeks.

Online services of Estonian banks, media outlets and government bodies were taken down by unprecedented levels of internet traffic.

Massive waves of spam were sent by botnets and huge amounts of automated online requests swamped servers.

The result for Estonians citizens was that cash machines and online banking services were sporadically out of action; government employees were unable to communicate with each other on email; and newspapers and broadcasters suddenly found they couldn't deliver the news.

Liisa Past was running the op-ed desk of one of Estonia's national newspapers at the time, and remembers how journalists were suddenly unable to upload articles to be printed in time. Today she is a cyber-defence expert at Estonia's state Information System Authority.

"Cyber aggression is very different to kinetic warfare," she explained. "It allows you to create confusion, while staying well below the level of an armed attack. Such attacks are not specific to tensions between the West and Russia. All modern societies are vulnerable."

That means that a hostile country can create disturbance and instability in a Nato country like Estonia, without fear of military retaliation from Nato allies.

Shadowy forces

The alliance's Article Five guarantees that Nato members defend each other, even if that attack is in cyberspace. But Article Five would only be triggered if a cyber-attack results in major loss of life equivalent to traditional military action.

Identifying who is responsible also makes retaliation difficult. The 2007 attacks came from Russian IP addresses, online instructions were in the Russian language and Estonian appeals to Moscow for help were ignored.

The physical destruction wrought by the riots was followed by a devastation of the country's networked institutions

But there is no concrete evidence that these attacks were actually carried out by the Russian government.

On condition of anonymity, an Estonian government official told the BBC that evidence suggested the attack "was orchestrated by the Kremlin, and malicious gangs then seized the opportunity to join in and do their own bit to attack Estonia".

Hostile states often count on copycat hackers, criminal groups and freelance political actors jumping on the bandwagon.

2007 was a wake-up call, helping Estonians become experts in cyber defence today. "It was a great security test. We just don't know who to send the bill to," says Tanel Sepp, a cyber security official at Estonia's Ministry of Defence.

The Bronze Soldier attacks may be the first suspected state-backed cyber-attacks on another nation.

But since then cyber warfare has been used all over the world, including in Russia's war with Georgia in 2008, and in Ukraine. "Cyber has become a really serious tool in disrupting society for military purposes," says Tanel Sepp.

Information warfare: Is Russia really interfering in European states?

Is cyber-warfare really that scary?

That's why Estonia's government has now set up a voluntary Cyber Defence Unit. Since Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea, the Estonian Defence League has been much reported on by the international press: at weekends 25,000 volunteers don fatigues and head to the forests to learn how to shoot.

Less well known is the shadowy Cyber Defence Unit.

Once bitten

The country's leading IT experts are also trained by the Ministry of Defence. But in addition they are security vetted and remain anonymous.

They donate their free time to defending their country online by practising what to do if a major utility or vital service provider is brought down by a cyber-attack.

It's the sort of private sector talent the state could never usually afford to employ.

But the memory of 2007 is a good recruiting sergeant. The attacks have stuck in the national consciousness by proving to Estonians the importance of cyber security.

Ten years after the attacks, the Bronze Soldier is still a reminder how much Estonia's complicated past can disrupt the present.

- Published31 March 2017

- Published12 November 2015

- Published23 February 2017

- Published7 December 2015