Covid: How busy are hospitals in England?

- Published

When announcing the national lockdown, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the NHS risked being overwhelmed if the measures weren't taken.

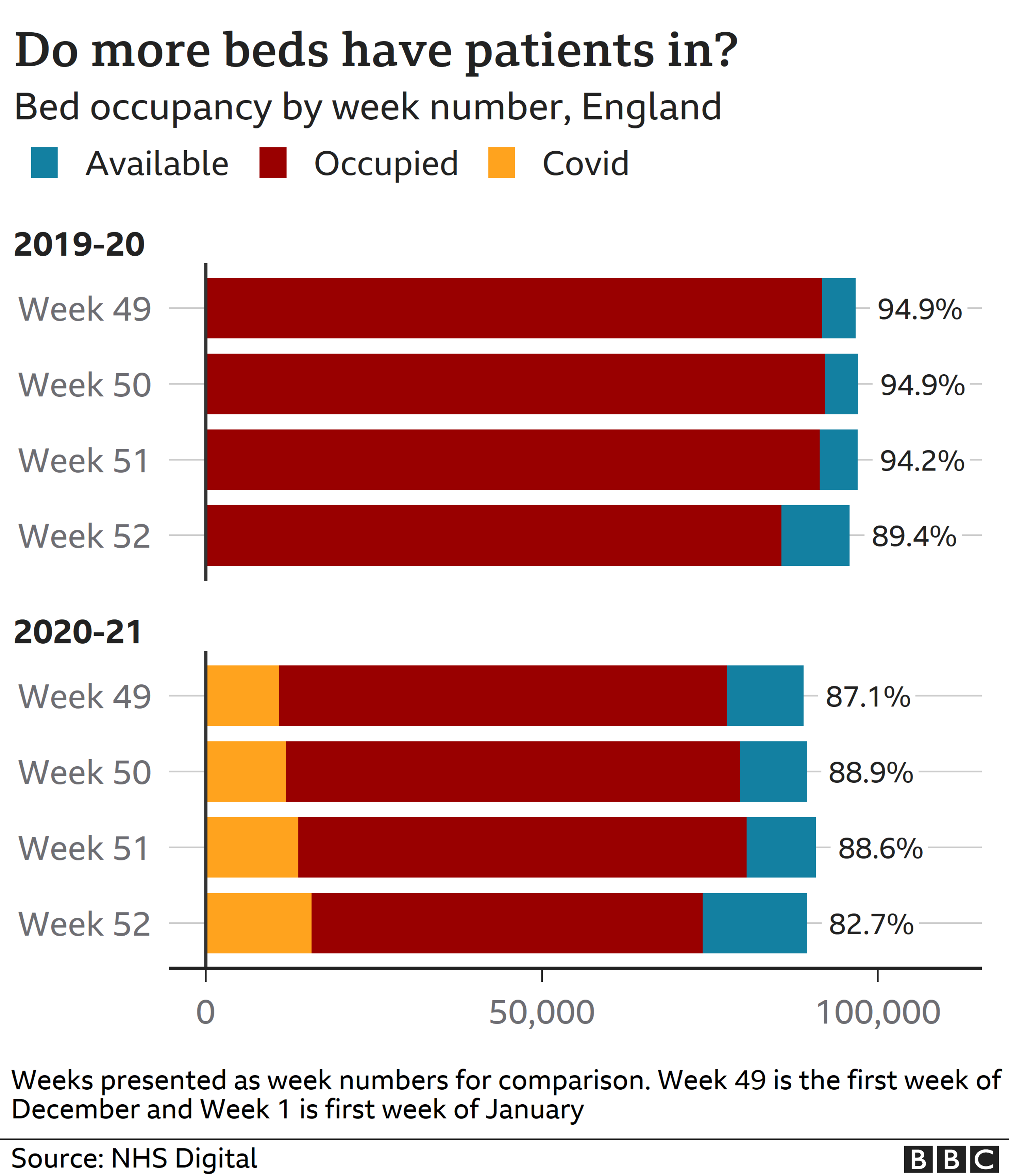

But statistics suggest that the proportion of beds currently occupied by patients is actually lower than usual.

So how can both things be true?

What is different this year?

Winter is normally an incredibly busy time for the NHS, coinciding with the peak of the flu season.

This is why we often see new stories at this time of year about patients facing long waits for care and ambulances struggling to get patients into emergency departments.

But this year, the system is facing the added pressure of preventing coronavirus spreading between patients while anticipating surges in cases.

The changes this year include:

Less space for beds due to the need for larger gaps between them

The division of wards into three zones: those for people with coronavirus, those awaiting test results and those who have tested negative

Increased infection control - including cleaning and putting on personal protective equipment (PPE) - which takes up staff time

Increased critical care beds and patients, which require more intensive staffing

Combined, these factors mean that hospitals have less capacity than usual, meaning fewer beds are available for fewer patients.

In total, NHS hospitals in England have about 7,000 fewer available beds than usual.

What does the data show?

The data shows that hospitals were at about 87% occupancy in December and early January, however this figure increases to just over 90% in London and the South East.

This means that for every 10 hospital beds available across England, roughly nine had a patient in them on any given day.

This occupancy rate is actually noticeably lower than a usual year. In a normal winter, occupancy tends to average between 93% and 95%.

But NHS England warns against using direct comparisons because - as mentioned - you wouldn't exactly be comparing like for like in the way the hospitals are being run.

Effectively, bed occupancy shows how many beds are available should patients need them, but what it doesn't paint a picture of is how much work is needed to tend to these beds.

And this year, with increased infection control and the movement of staff to intensive areas, that workload has increased.

Even in early December, NHS Providers, which represents NHS trusts, said that already the pressures felt as bad as a normal year despite fewer patients and lower bed occupancy.

How much extra room is there?

In theory, there are 12,000 free beds in NHS hospitals in England.

But no hospital ever aims to be close to 100% occupancy.

Guidance actually recommends that an optimum level is about 85% occupancy. This is to reduce the risk of staff becoming overstretched or being unable to deal with any unexpected surges of patients for whatever reason.

The coronavirus has meant that hospital bosses have felt the need to ensure even more wiggle room than usual, because the virus tends to spread quickly.

The number of patients in hospital in England with the virus has increased by 8,000 since the start of December, hitting 22,534 on 1 January, a record high.

And once the virus is prevalent in a community, it affects hospital staffing as some of them need to take time off due to sickness or self-isolation. During the first wave in April, 6.7% of staff were absent from work, compared with 4% in the previous year.

So while hospitals are feeling these increased winter pressures, they need to ensure that they still have that wiggle room.

Outside the NHS, the government can work with private hospitals and also look towards the Nightingale hospitals, but this also might be affected by staffing pressures.

Why are operations being cancelled?

To create that wiggle room, there has been a big decrease in patients coming in for non-urgent operations and outpatient appointments, to ensure that space is there and pressures are not increased.

Even in September 2020, when hospitals were beginning to increase the number of operations carried out, these were still 25% lower than in previous years.

This also helps explain why there are also fewer patients in hospitals this year, as well as fewer beds.

The impact of this is a large backlog and the potential for certain treatments - such as cancer care - being delayed.