Did we see a Christmas coronavirus spike?

- Published

It is almost a month since Christmas was "downsized" across the country. But in many parts of the UK, people were allowed to meet in Christmas "bubbles" - if only for just one day. So what impact did this have? The overall picture shows a sharp increase in cases around this time.

However, a closer look at the numbers suggests this trend was already happening and was probably caused by the new, more infectious variant of the virus rather than increased contact between people.

What happened over Christmas?

Firstly, a quick reminder of the rules.

Initially, the plans for the UK would have allowed up to three households to mix indoors between 23 December and 27 December.

But on 19 December, Prime Minister Boris Johnson scaled back these Christmas bubbles because infections were beginning to rise sharply, driven in part by a new variant of Covid-19, across south-east England.

Gatherings were banned in most of this area, including London, Essex and Kent, (except for people in support bubbles), while in the rest of England, people were allowed to meet only two other households on Christmas Day.

Decisions in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland saw the window for gatherings reduced too, and in Wales only two households were allowed to gather.

Did people celebrate Christmas together?

A survey from the Office for National Statistics suggests, external that roughly half the population in Great Britain who were allowed to hold gatherings did so.

However, this doesn't tell us about where in the country gatherings happened or who they involved.

Research into social contact across the UK, conducted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, external (LSHTM), suggests there was a decline in contact to mid-November levels over the Christmas period, driven by closed schools and workplaces.

This means contacts, which are defined as face-to-face meetings of around five minutes or more, were roughly the same as during the second English lockdown.

It was also a big decline from contacts seen in the three weeks up to Christmas.

Transport use dipped over the Christmas season

This is important when looking for spikes because the virus thrives on close contact between people so less contact means fewer infections.

"I was expecting to see a reduction in contacts because of the closure of schools and workplaces, but potentially an increase in risky contacts," says Prof John Edmunds, from the LSHTM's faculty of epidemiology and public health and a member of the government's scientific advisory body, Sage.

He says the research did not show an increase in contacts with more vulnerable groups, such as elderly people, as expected. This suggests people may have decided not to spend Christmas with those at higher risk from the virus.

So did cases go up?

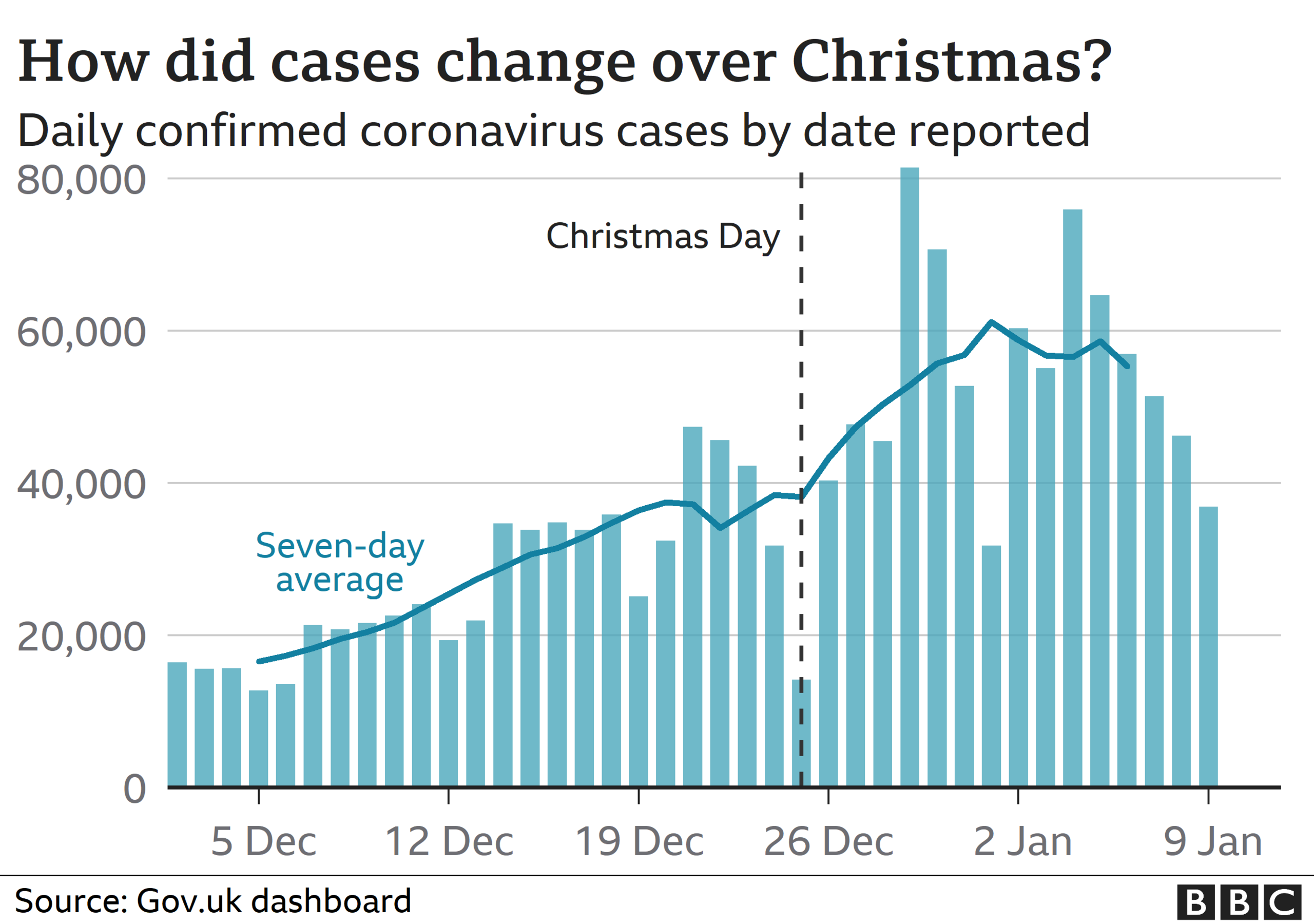

Across the UK, cases continued to rise over and after the Christmas period.

However, whether this was influenced at all by the Christmas bubbles is very difficult to say.

Looking at the data, we might expect to start seeing the impact of a Christmas spike in the first week of the New Year. This is because the typical incubation period - the time for symptoms of the virus to appear - is, on average, about five days.

That means the sharp increases seen between the 20 and 30 December cannot be attributed to the holiday.

In the first few days of 2021, cases continued to rise at the same pace as before Christmas and, in early January, appear to have peaked, although it is too early to tell if the decrease will be sustained.

"I actually can't see any convincing evidence that Christmas actually did anything to make things worse at all, but trying to prove it definitely, one way or another, is not necessarily that easy," says Paul Hunter, a professor at the University of East Anglia's medical school.

His mathematical modelling suggests cases have increased in line with trends that were happening before households starting mixing over Christmas.

And clear analysis on case rates around Christmas is affected by a number of things, including:

The spread of the new, more infectious variant across the country which would result in spikes regardless of Christmas bubbles

Different lockdown rules in different parts of the UK, which could see cases rise more quickly in some parts than others

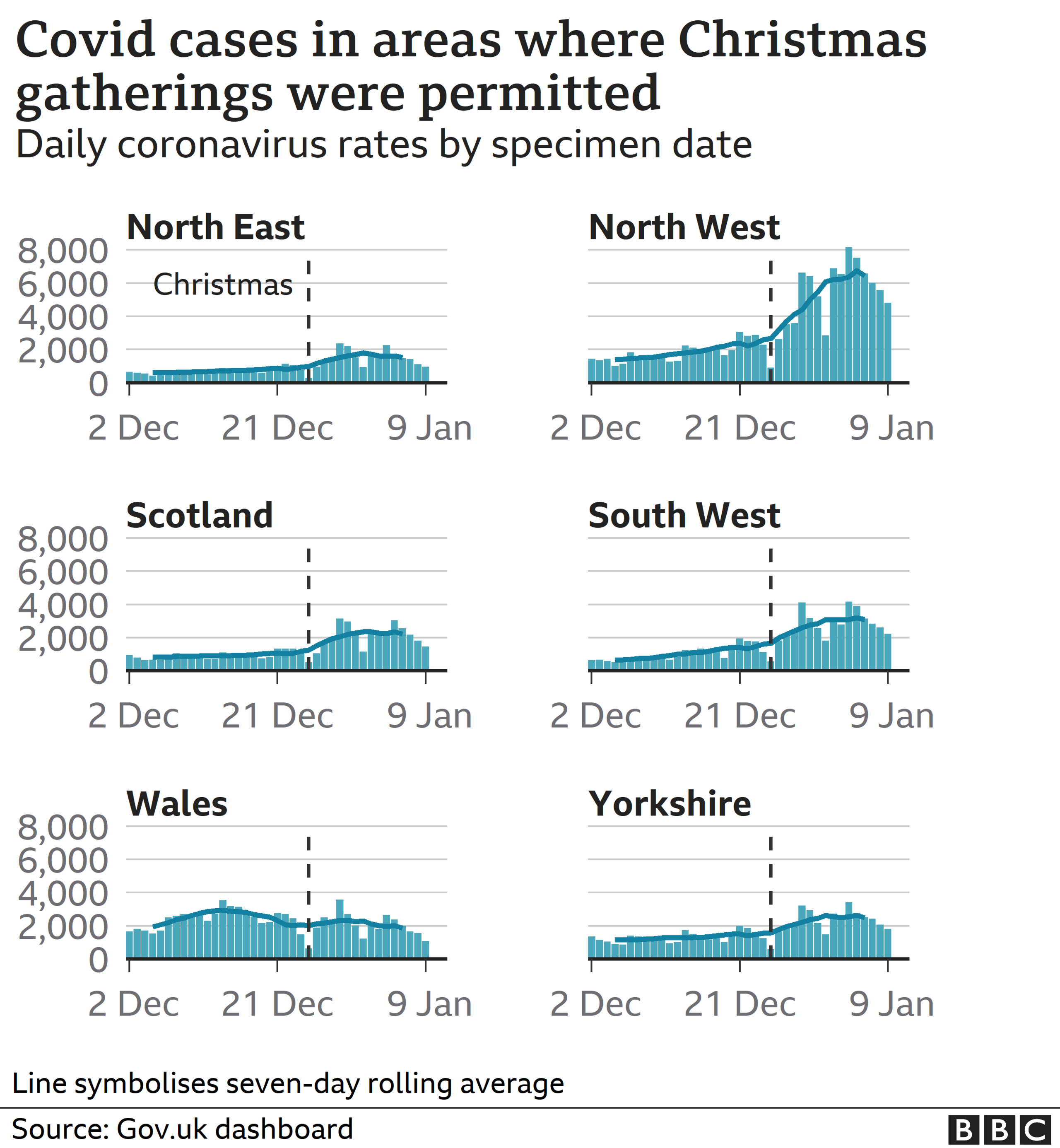

When we look specifically at parts of the country where gatherings were allowed, and the new variant was less prevalent, the trend is fairly similar to the country as a whole, albeit with a time lag of a few days.

In north-east and north-west England, Scotland and Wales, we see cases rising around the holiday.

But those rises start happening before or a couple of days after Christmas Day. This makes it unlikely that the upward trend is sparked by festive bubbles, because there wouldn't have been enough time for people to start exhibiting symptoms if they caught it during the holiday.

Data from the Office for National Statistics infection survey, external highlights that these increases start happening around the same time the new more infectious variant increased in those areas.

So, it could be that the new strain helped steepen an upward trend that was happening before the holiday.

Did anyone catch the virus at gatherings?

The fact that there hasn't been a specific spike after Christmas doesn't mean that people didn't catch the virus at festive gatherings.

"I am sure that there were some additional cases as a result of contact over Christmas," says Prof Edmunds. "That is almost inevitable with the very high levels of infection that we have at the moment.

"However, the major spike that we saw [around Christmas] was most likely due to the new strain not increases in contacts."

There is limited official data on where people actually catch the virus, but the test-and-trace programme , externalin England does ask those who test positive where they have been in the days up to developing symptoms.

In the week ending 3 January, around 20,000 people said they had visited friends or family in the run-up to testing positive. This was roughly double the number on the week before.

This data doesn't mean they caught the virus there but gives an indication of where people had been. It also represents a relatively small proportion of all events people recorded.

For example, in the same week 80,000 people said they had been shopping, before testing positive.