The disinformation tactics used by China

- Published

Facebook and Twitter removed accounts linked to China during unrest in Hong Kong in 2019

The Chinese embassy in London has criticised the BBC following a documentary about Chinese disinformation campaigns.

There have also recently been a series of denials from Beijing over reports into forced imprisonment of its minority Uighur population - these have included baseless accusations against media and human rights organisations.

In the latest attack, an official falsely claimed a Uighur interviewee on a BBC programme was an actress.

So what tactics does China use in the spread of misleading and false information?

Increasing anti-BBC coverage

There have been almost daily anti-BBC articles in Chinese state media since mid-February.

It follows a decision by the UK broadcasting regulator Ofcom to revoke the licence for China's state-run overseas broadcaster, CGTN.

For years, China has broadly criticised Western outlets for reports on affairs in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China, saying they should not intervene in China's "internal affairs".

But these latest attacks on Western media are a clear escalation.

Chinese domestic media outlets have praised their government for banning the BBC's World News channel, although it was only available in some international hotels and residential compounds where foreigners live.

Reports from leading outlets like China's Global Times have criticised the "Cold War" mentality when it comes to China - on topics ranging from Hong Kong, the Uighur population of Xinjiang and the Covid-19 pandemic.

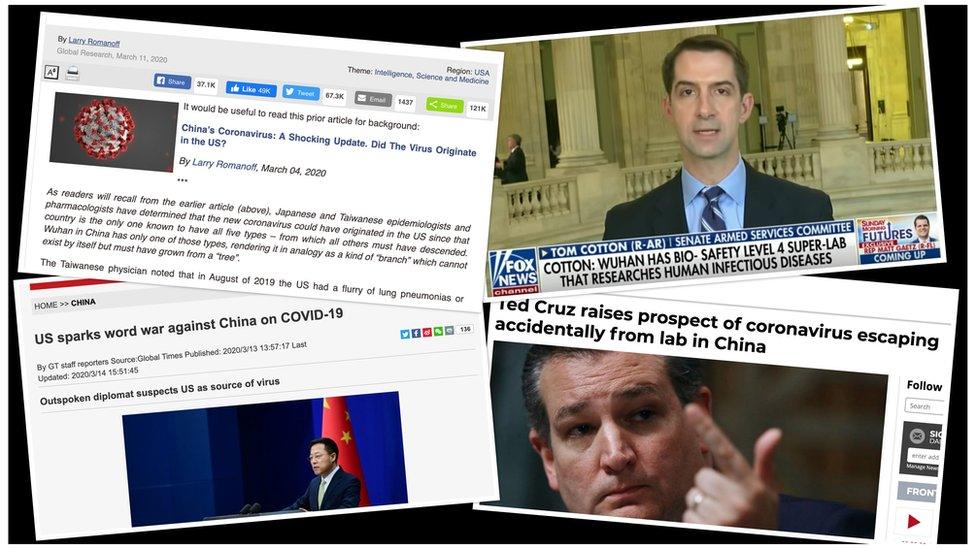

When China was facing a backlash over its handling of early stages of the pandemic last year, and some US officials were floating the theory that the virus could have escaped from a Wuhan lab, CGTN started to push its own conspiracy theory.

Despite a complete lack of evidence, the station suggested the virus originated at a military base in Maryland in the US and was brought to China by American soldiers during an athletics competition.

Find out more

'Wolf warriors' on social media

In recent months, China experts have noticed dozens of new and highly active official social media accounts representing Chinese embassies and leading diplomats.

This has become known as "wolf warrior" diplomacy. The best-known account belongs to Zhao Lijian from the Chinese foreign ministry.

He caused controversy in March after tweeting articles suggesting that coronavirus originated in the United States.

The US and China traded unverified theories about the origins of coronavirus

Those tweets have been shared more than 40,000 times and referenced in 54 different languages, according to research, external from the Digital Forensic Research Lab, part of the Atlantic Council think tank.

Popular hashtags referencing the posts have made waves at home too - they've been viewed by users of Chinese social network Weibo more than 300 million times.

In December, Zhao Lijian was widely criticised for sharing a fake image of an Australian soldier killing an Afghan child, for which China refused to apologise.

'Keyboard army'

China draws on millions of citizens to monitor the internet and influence public opinion on a massive scale online. These recruits are known as the "50 cent army" - so named because of reports that they were paid 0.5 yuan per post.

This "keyboard army" has long been active on Chinese social media platforms. Its aim has been to aggressively defend and protect China's image overseas.

When tweeting in English, the messages are aimed at a Western audience, much like troll farms in Russia that sow discord.

To the unsuspecting reader, they might appear as patriotic citizens acting independently, but frequently they are taking directions from Chinese authorities.

One example is the way in which video footage of violent protests in Hong Kong in 2019 was promoted on social media via this keyboard army using terms such as "terrorism", while coverage of peaceful protests was censored.

In August 2019, Facebook and Twitter announced they had removed accounts linked to a state-backed information campaign.

Facebook said: "Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities, our investigation found links to individuals associated with the Chinese government."

Twitter identified more than 900 accounts from China. But these were only the most active components of the campaign, which the company said involved some 200,000 accounts, external.

Fake social media accounts

A BBC investigation in May 2020 found hundreds of fake or hijacked social media accounts promoting pro-China messages on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Some 1,200 accounts targeted people critical of how Beijing was handling the pandemic.

There was no definitive evidence tying these accounts to the Chinese government, but it did display similar characteristics to the state-backed network removed by Facebook and Twitter in 2019.

It also resembled another network dubbed "Spamouflage Dragon", which pumped out pro-China posts and attacked critics with spam, which was uncovered by the social analytics firm Graphika, external.

Subsequently Twitter said it had removed more than 23,000 accounts linked to China involved in a range of "manipulative and co-ordinated activities".

In response to comments made by Yang Xiaoguang, from the Chinese Embassy in the UK on the BBC Today programme, a BBC spokesman said: "We completely reject these claims and stand by our journalism. BBC News reporting in Xinjiang has been accurate and impartial - we did not use any false images and the interviewee who appeared on the BBC was not an 'actress' as claimed."

Additional reporting by Jack Goodman