Covid: What do we know about global youth unemployment?

- Published

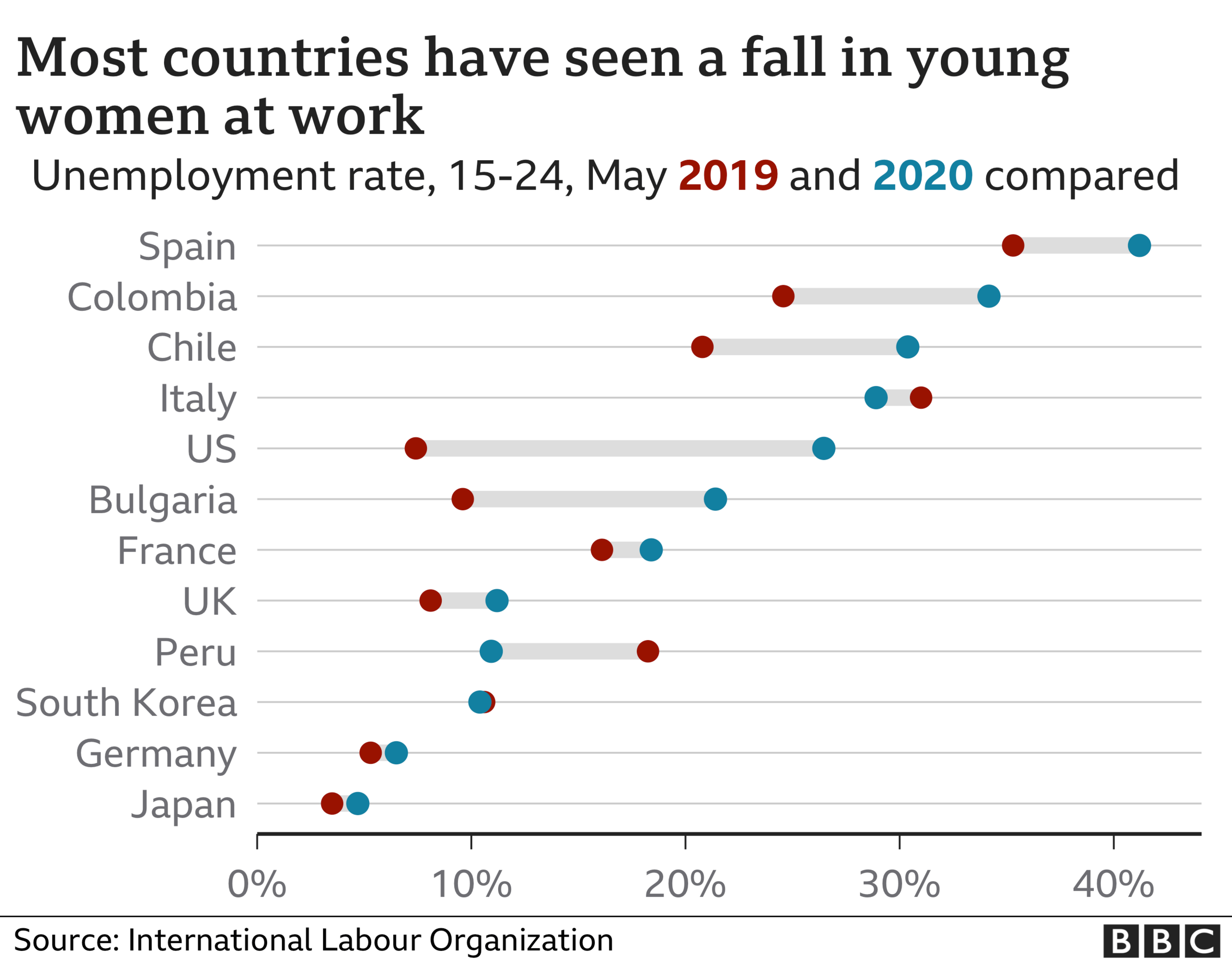

Young women have been most affected by the economic consequences of Covid

How has the pandemic altered the landscape for young people entering the job market? For the last 18 months, Covid-19 has led to unprecedented disruption across the world. While older people have been the most at risk from the virus itself, the young have disproportionately suffered from its economic fallout.

"The young jobless have been stuck in a Covid-19 limbo-land," according to Sher Verick, from the International Labour Organization (ILO).

"This crisis has...not only led to the closure of businesses and job losses, but the lockdown measures have also severely constrained young people's ability to search for a job."

The unemployment rate among young people was 14.6% in 2020, according to the ILO.

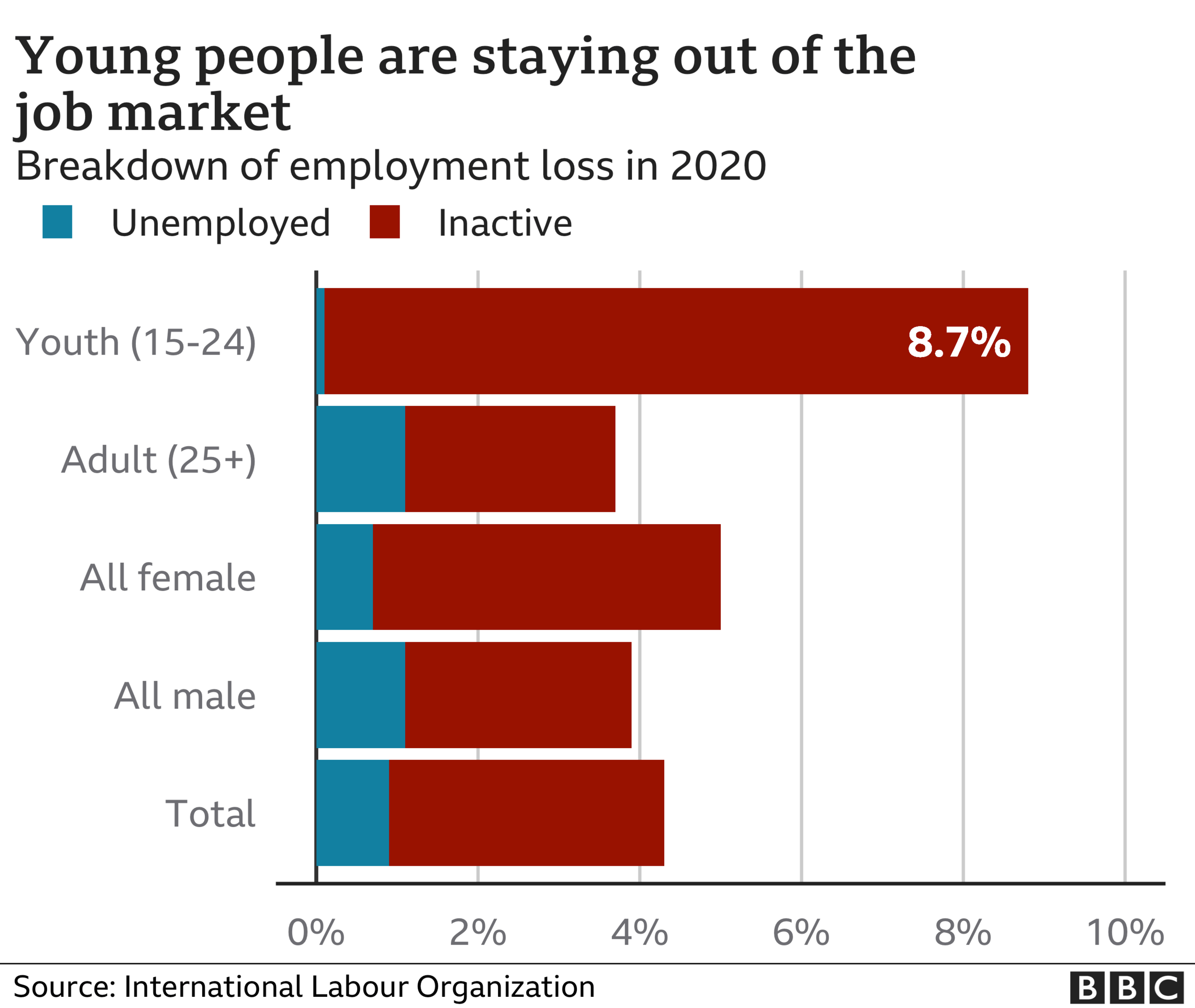

Economists distinguish between people who are unemployed and people who are "economically inactive".

Those who are out of work but are looking for a job are considered unemployed. People who are not actively looking for a job (this includes those who may have given up searching for employment), or are in the process of starting their own business, are considered "economically inactive".

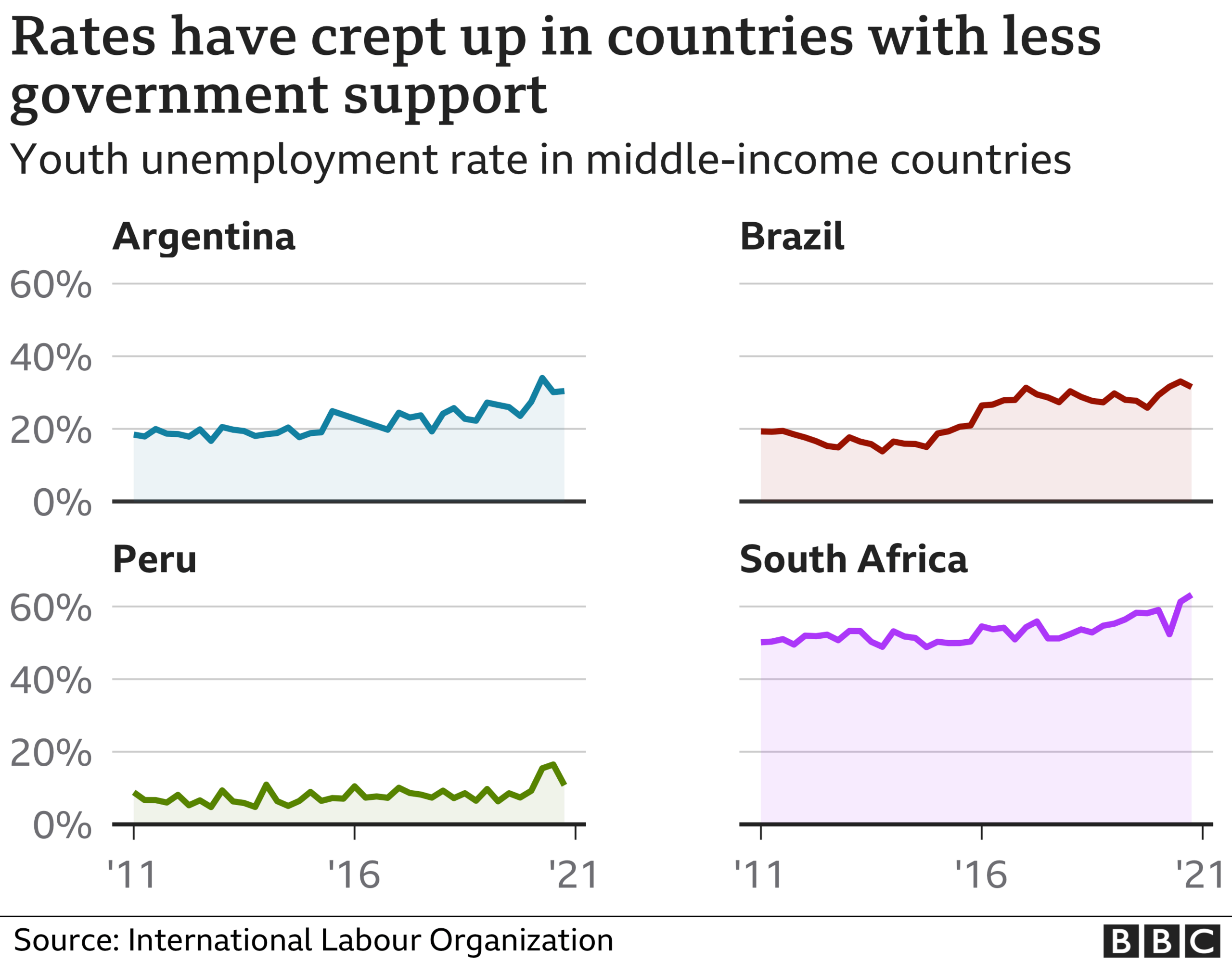

The biggest jumps in youth unemployment have occurred in what economists describe as "middle-income countries" such as Argentina, Brazil, South Africa and Peru.

Middle-income economies were strong enough to have had thriving hospitality industries before the pandemic, for example.

However, they often lacked the economic resilience to go into extended lockdowns or provide generous support packages to businesses and workers.

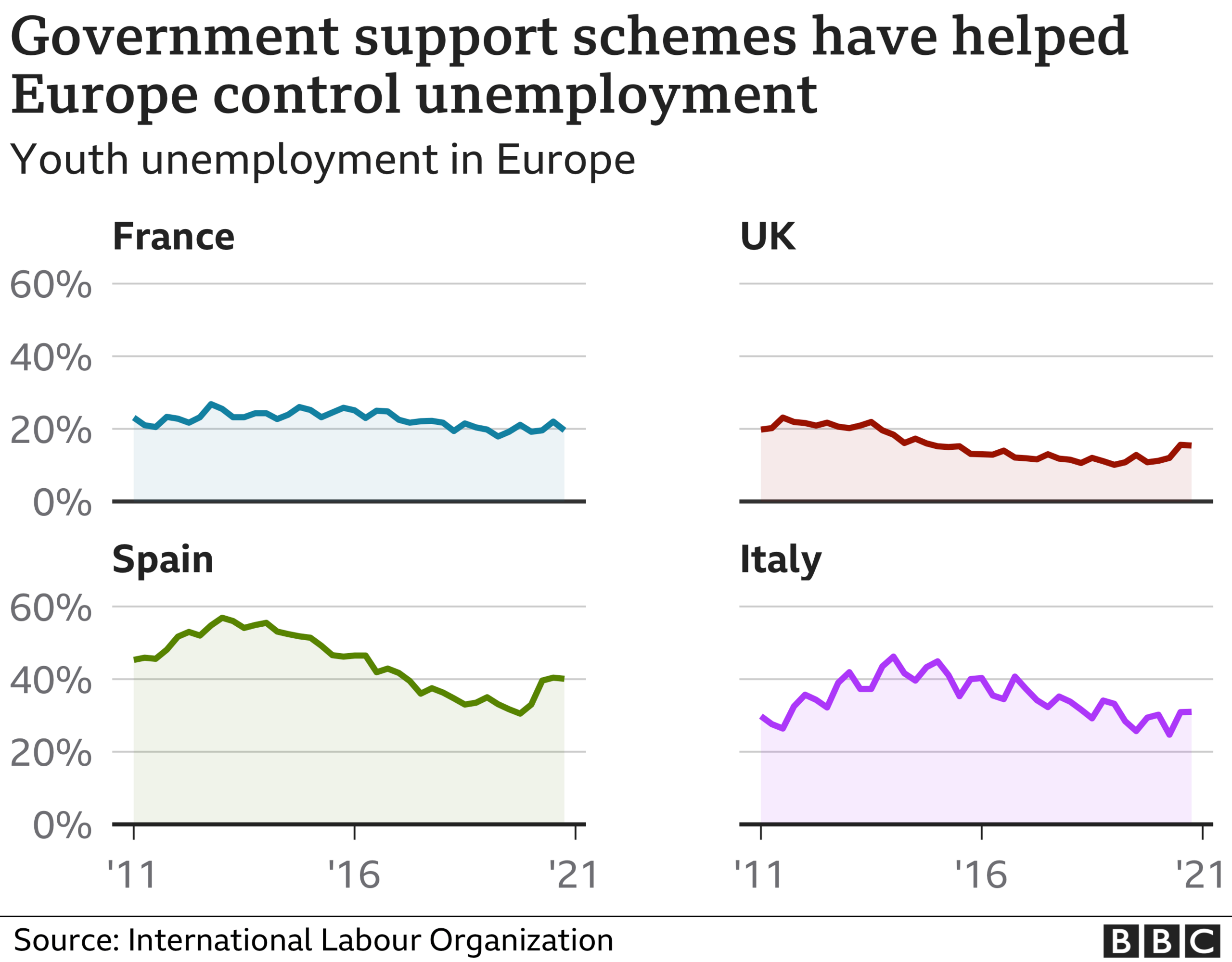

In Europe, the pandemic is also posing an economic threat to younger generations.

Countries such as Spain and Italy were still recovering from the effect of the eurozone crisis when the pandemic struck. In Spain, the recovery went into reverse.

But stronger economies such as France and the UK were able to keep youth unemployment relatively stable. They used expensive government support schemes to make grants, loans and tax breaks available to struggling businesses and help employers pay staff who have been unable to work.

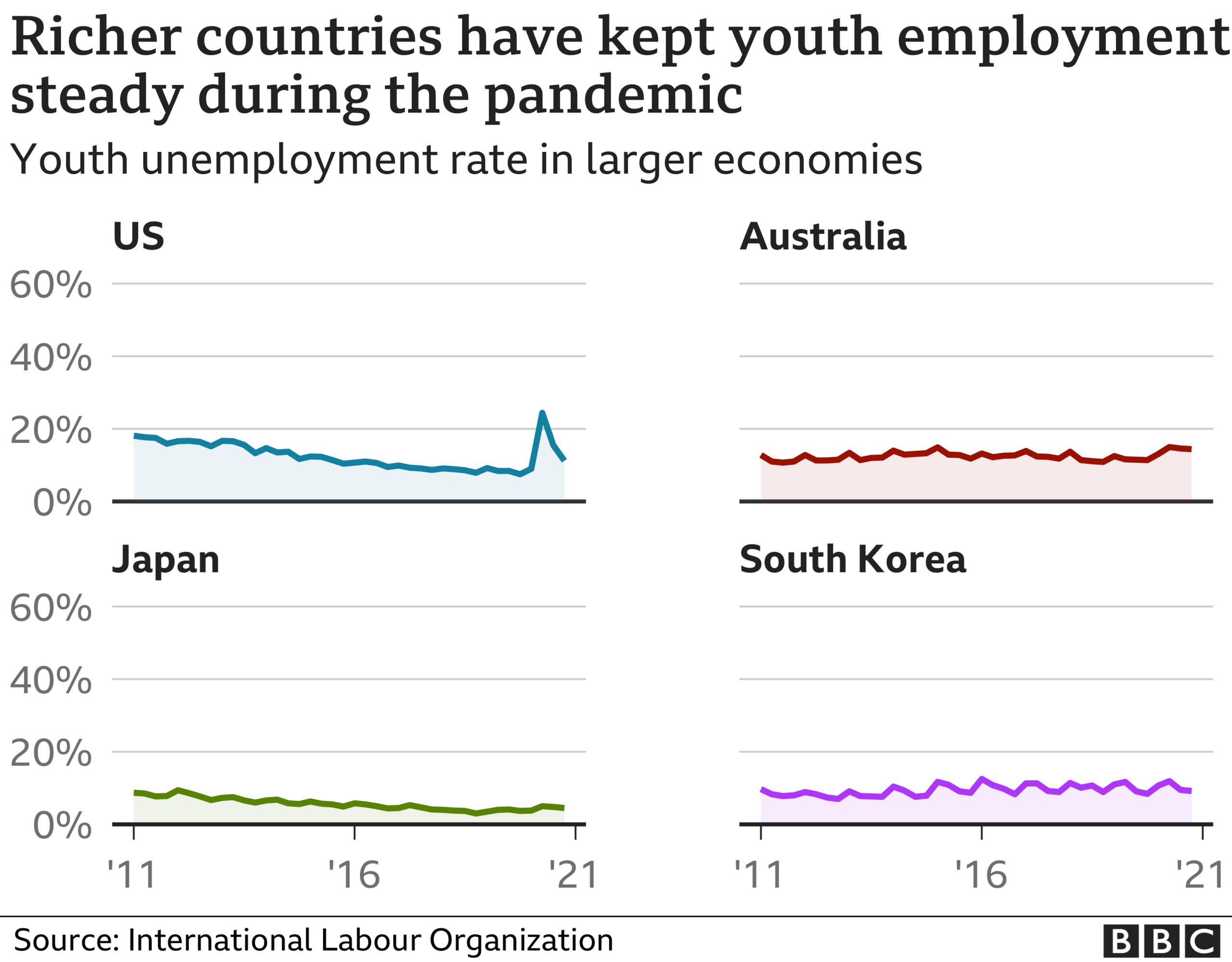

Other big economies saw a spike in youth unemployment in the first part of the pandemic, although government policies have been able to keep this under control.

In Japan and South Korea, rates of youth unemployment have been almost completely unchanged. Meanwhile in the USA, it shot up before the government intervened with heavy stimulus spending by President Trump and President Biden.

Young women have generally suffered more from the economic consequences of Covid than young men.

That is partly because women are more likely than men to work in some of the hardest-hit industries such as hospitality.

The ILO estimated, external that around the world, about 55% of workers in hotel, catering and tourism were women.

Women were also more likely to have to stay at home and look after children when schools closed.

In middle-income countries, the unemployment rate for men is 23.7%, while for women it is 29%.

Before the pandemic struck, youth employment rates were still at a lower level than they had been before the global financial crisis in 2007-2008.

That's because during and after a recession, youth employment tends to recover much more slowly than overall employment.

School leavers and university graduates can miss out on valuable work experience.

Once the economy returns to normal, it becomes harder for them to compete with older and more experienced workers as well as the next generation of school leavers and graduates.

Mr Verick said: "Youth employment recovers slowly following a recession because young people don't have the same work experience and access to networks that older people have, which means it is harder for them to compete for the fewer jobs that are available after a crisis."

Researchers have shown that graduating or leaving school during a recession can have a long financial hangover, because individuals arrive late on the first steps of the career ladder.

According to economists, external at the University of Leicester and the University of Nottingham, each month of unemployment between the ages of 18 and 20 leads to a permanent income loss of 1.2% over the course of a career.

Dr Sara Lemos, an economics lecturer at the University of Leicester, says that when young people spend time out of work: "They lose their skills, confidence and ability to reinsert themselves in the labour market, and lag behind.

"Employers see that inability to get a job as a signal that other employers have been refusing that worker, and assume that worker must not be productive enough to be hired.

"Naturally, the longer a worker stays unemployed, the stronger the stigma gets, and the harder it is to find a good job, and good pay."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

WHAT WE DON'T KNOW How to understand the death toll

TESTING: Can I get tested for coronavirus?

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area