What is austerity and where could 'eye-watering' cuts fall now?

- Published

Billions of pounds worth of cuts to public spending are expected to be announced by the Conservative government on 17 November in what will be seen as a new period of austerity.

What is austerity?

In 2010, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government embarked on a programme of deep spending cuts and tax increases.

It was aimed at reducing the country's massive deficit - where it was spending much more money than it was raising in taxes - after it bailed out banks during the 2008 financial crisis.

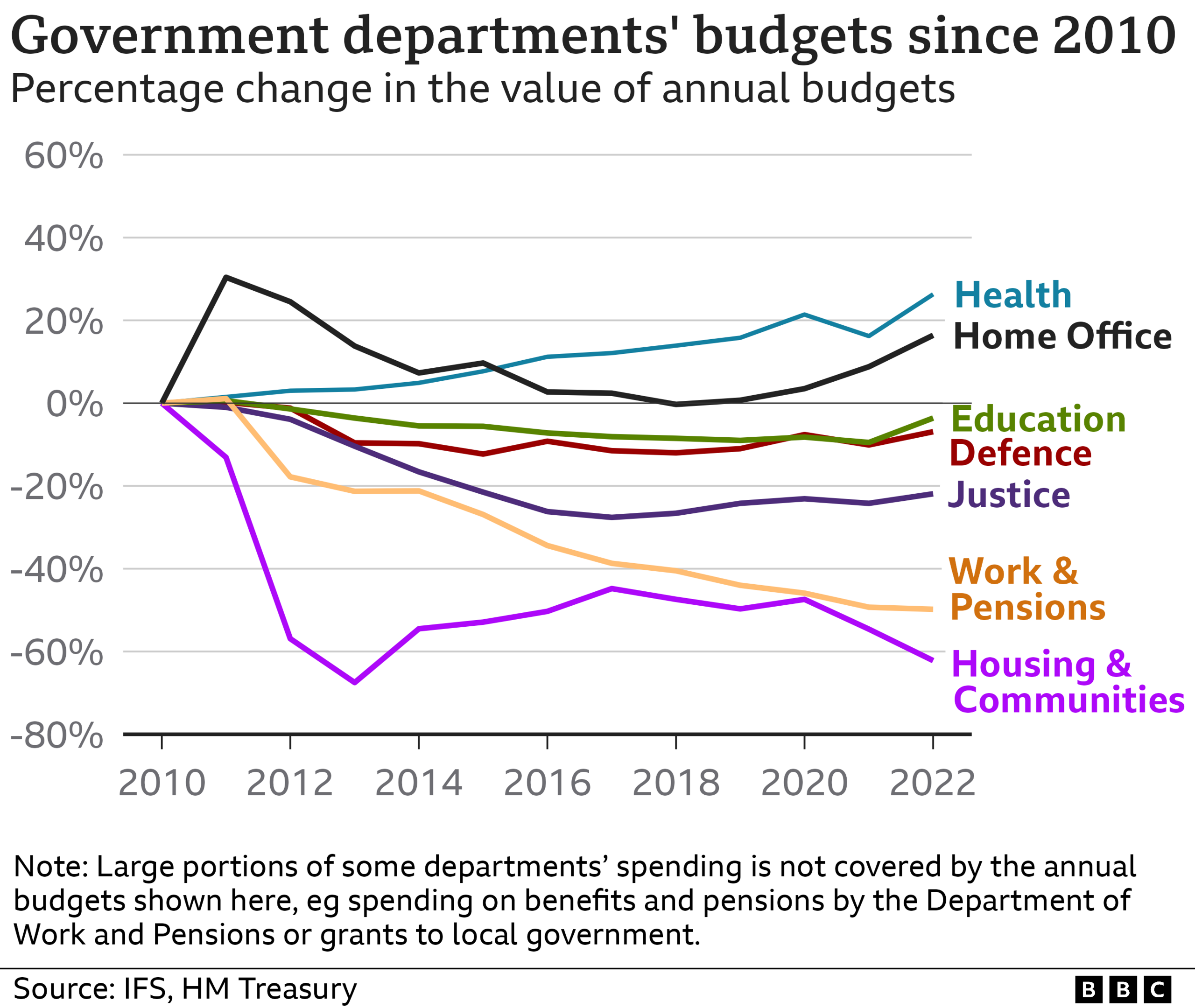

As a result, many departments still have less spending power now than they had before 2010.

The chart above shows the money controlled by departments in their annual budgets. For some, like the Department of Health and Social Care, that's the majority of the money they spend. For others, like the Department of Work and Pensions, it's only a small proportion and covers staffing costs and running services like job centres but not the bulk of their spending: direct payments on pensions and benefits.

The government's priorities have meant that health, pensions and, until recently, overseas aid have had more money, while spending on defence, education and public order fell.

Government spending as a whole is below the level it was in 2009-10 as a proportion of the size of the economy.

So, is there room for further cuts?

Health

By Nick Triggle, health correspondent

An ageing population and rising demand mean health is one of the biggest recipients of government spending. In England, the annual budget is nearly £168bn or more than 40p in every £1 the government spends running public services.

It was one of the few areas to escape cuts during the austerity years. Before 2010, the NHS budget rose by about 4% a year once inflation is taken into account. Under austerity, rises were limited to 1.6%.

Performance deteriorated as savings were made, with waiting times growing - a problem worsened by Covid.

Nearly half of the NHS budget goes on salaries - but there are significant staff shortages, with one in 10 posts vacant.

NHS bureaucracy could be a target, but research by the King's Fund suggests there is not much left to trim.

Some believe the solution may lie in rethinking what the NHS is for - questioning whether, for example, so much should be spent on treating seriously ill patients who are close to death.

Rationing care though is politically very difficult.

Social care

By Alison Holt, social affairs editor

Councils, which fund the majority of support for people in their own homes and in care homes, were particularly hard-hit during austerity.

According to the King's Fund think tank, real terms spending, external on care per head of the adult population fell from £593 a year in 2010-11 to £585 in 2020/21.

An ageing population and more people living with complex health issues mean demand for support is increasing.

However, low pay and zero-hours contracts make it hard to recruit staff. Add in post-pandemic burn-out and the cost-of-living crisis and you have a sector on its knees. More than half a million people are waiting for council care services and there are 165,000 vacancies for care staff - both new records.

That has a knock-on effect on the NHS, with people needing care being stuck in hospitals.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has previously campaigned for additional care funding, so any decision to cut money now is likely to be greeted with anger and dismay.

One option may be to delay existing plans to introduce an £86,000 cap in England on people's lifetime care costs. The government has allocated £5.4bn to deliver this reform, which is due to start in October 2023.

Schools

By Kate McGough, education reporter

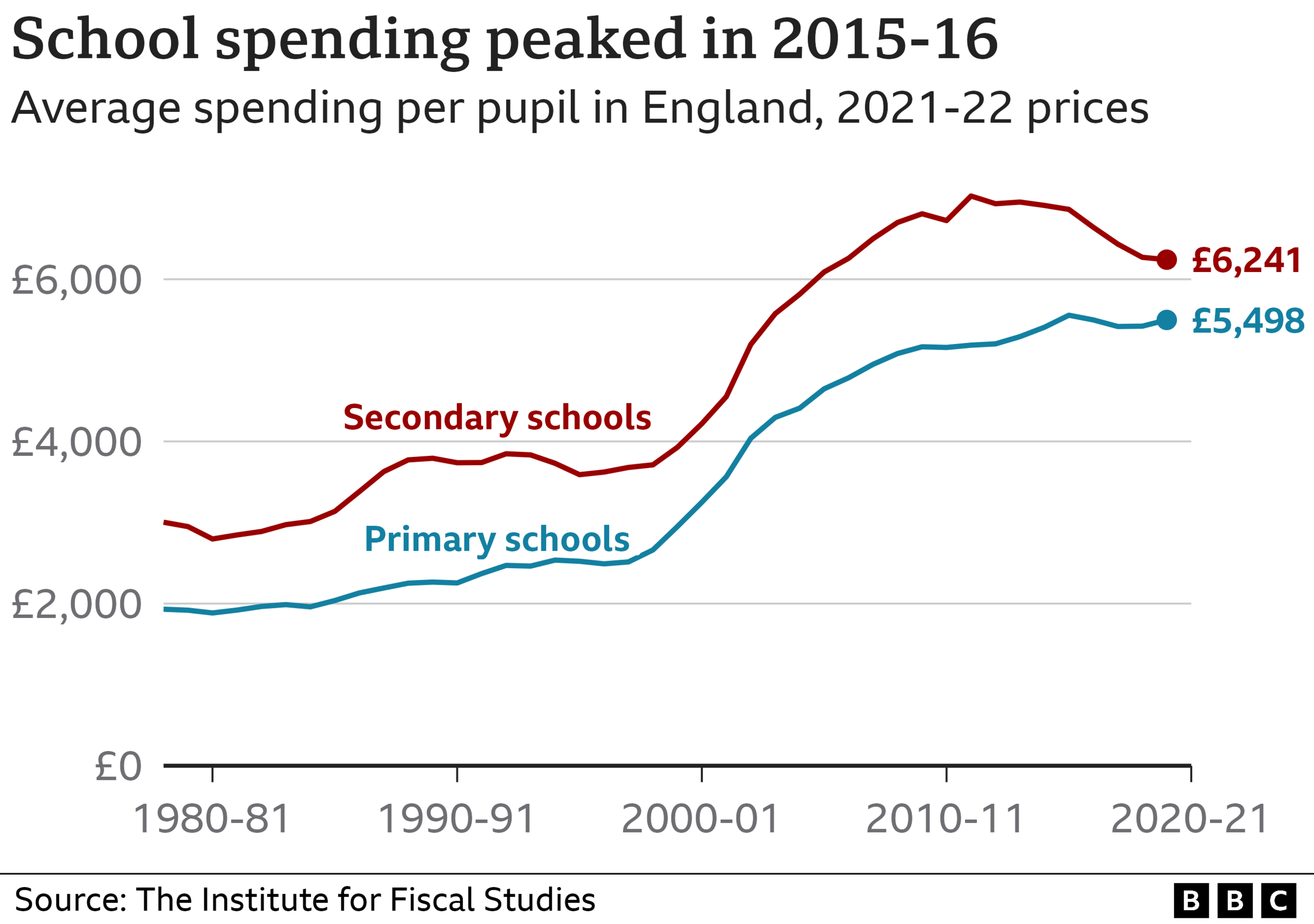

After a decade of spending cuts in schools, ministers had promised to restore per pupil funding levels to what they were in 2010 by the end of the current Parliament.

But the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) think tank said recently, external that spending per pupil in England is still expected to be 3% lower than 2010 levels by 2024-25.

During the austerity years, teachers' pay was subject to freezes and caps. In response to the cost-of-living crisis, the government has promised a 5% pay rise for experienced teachers. But, even factoring this in, the IFS estimates that the value of their pay - after adjusting for rising prices - will have fallen by 14%, external between 2010 and 2023.

The 5% rise will also be funded from existing school budgets, which one union has said are already "at breaking point".

Staff shortages mean that schools are spending more on supply teachers. And they are also having to cope with higher energy costs, with government help only assured until April 2023.

Parents and pupils will feel the knock-on impact of the pressures schools are facing, with school trips and music lessons among the things heads are considering axing in order to avoid cutting staff.

Defence

By James Landale, diplomatic correspondent

The UK spends about £48bn a year on defence. That is about 2% of the size of the economy, which meets the target of defence spending required by the Nato military alliance.

Ex-Prime Minister Liz Truss promised to increase defence spending to 2.5% by 2026 and 3% by 2030. We do not know whether Rishi Sunak will commit to this.

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has said extra money is needed to increase the size of the army, invest in artillery batteries, electronic warfare and anti-drone capabilities, as well as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

Any cuts would mean less money for those areas. Even if defence spending does increase, the money will go less far because the pound is currently weak and so much military kit is priced in dollars.

There is also Ukraine. Whatever the result of the current war, the UK will probably have to use its defence budget in the future to help give Ukraine the military support it needs to deter future threats from Russia.

Welfare

By Michael Buchanan, social affairs correspondent

The welfare budget has seen huge changes and major cuts since 2010.

It is still substantial - about £88bn for working-age benefits. That is approximately twice what the country spends on defence, but half of health spending.

Much of that bill is spent addressing long-standing problems - topping up low-paid workers, helping families cope with soaring housing costs, or supporting people who are ill or disabled.

Working age benefits are now 7.5% lower - after adjusting for rising prices - than in 2009. They have failed to keep pace with prices in nine of the past 12 years.

Welfare changes and cuts have been the biggest contributory factor to the explosion in food banks over the past decade, according to the Trussell Trust.

One area of benefit spending that has grown massively in recent years is fraud. More than £5.5bn, or 13% of total spending on universal credit, was paid fraudulently last year.

Cutting that is already a government focus, and the Treasury is understood to be looking at making further inroads. But realising those savings cannot be guaranteed.

Housing

By Mark Easton, home editor

The big money in this sector goes on housing benefit - more than £20bn a year - which subsidises rents for both private and social housing tenants on low incomes.

The government is already looking to cut the housing benefit bill, by changing entitlement criteria and capping increases in social rents.

The former would hit some of the poorest households and the latter would hit the income of housing associations and councils.

It warns this will mean less money for maintenance, repairs and new homes. Some fear it would also undermine investment in energy efficiency and safety measures.

There are also big capital programmes, £11.5bn over five years for desperately needed affordable housing in England, and £1.4bn a year for social housing decarbonisation, a key part of the government's Net Zero strategy.

However, it is likely the chancellor will be looking for immediate savings from daily expenditure, and it is difficult to see many opportunities that will not impact on the most vulnerable households or on the housebuilding programme.

Police, courts and prisons

By Dominic Casciani, home and legal correspondent

In 2010, the Conservative-led government slashed spending across the criminal justice system.

That year, police strength in England and Wales was a record 143,000. By 2019, 20,000 officers had been cut and numbers were lower than for 30 years.

There are plans to recruit 20,000 new officers and - to date - about 15,300 have been appointed.

Extra officers should mean more criminals in court.

But since 2010, the government has closed 244 courts - 171 of which dealt with crime. A cap on the number of judges working left courtrooms locked. And the backlog worsened when Covid closed courts completely.

There is now a record of about 61,000 outstanding cases - with victims, witnesses and defendants waiting two years or more for trials to begin. Many lawyers quit criminal work because of low pay for publicly funded defence work.

The challenges in prisons have also worsened, with the number of offenders awaiting trial at a 14-year high. They are unable to restart their lives, or begin rehabilitation after sentencing

Judges could be forced by law to release some suspects into the community, if trial waiting times do not rapidly improve.

About 16% of prison officers are quitting annually and sickness rates are at a high - the main reason being mental ill health.

Climate

By Justin Rowlatt, climate editor

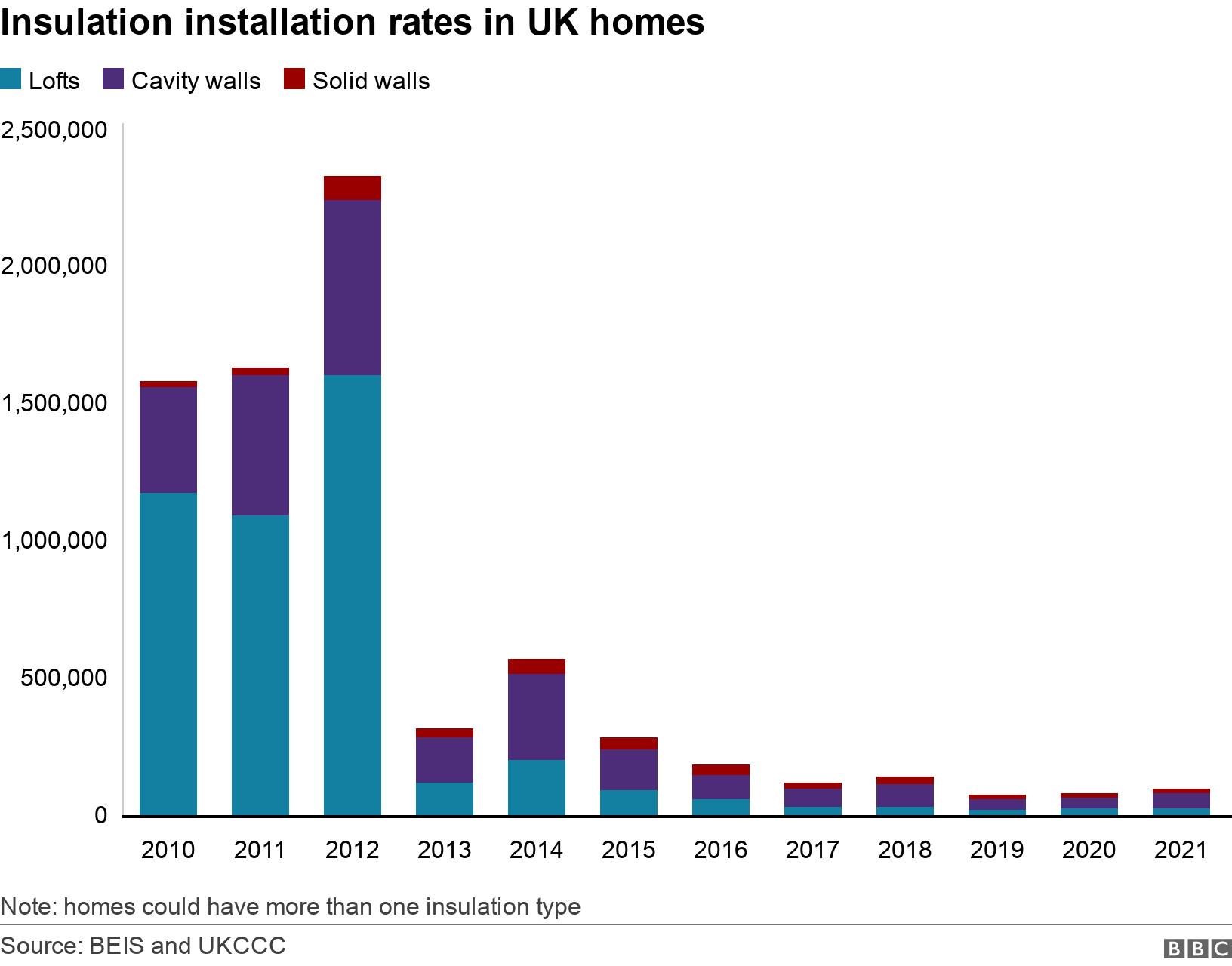

There are a few potential savings that could be made by reducing the already relatively paltry subsidies the government offers for home insulation, external and other energy efficiency measures.

The dilemma the government faces is that many of these schemes will actually reduce energy costs in the future. Cutting them would also add to the risk of the government failing to meet its legally-binding climate targets.

One easy opportunity to save money is launching a public information campaign to encourage us all to save energy. The EU has a target of cutting gas consumption by 15% and electricity use by 10%.

If a UK campaign achieved that it could reduce the government funding needed for the energy price cap.

Correction 17 November: In an earlier version of this article, a chart showing government spending in terms of departments' annual budgets was incorrectly labelled. This has been amended.

Are you affected by issues covered in this story? Please email: haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Or fill out the form below

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.