Can we trust economic forecasts?

- Published

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced more than £50bn of tax rises and spending cuts on Thursday.

Mr Hunt's Autumn Statement was accompanied by an assessment of his measures by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) - the independent spending watchdog which makes forecasts about the UK economy.

The chancellor cited the OBR 10 times during his speech, but some Conservative MPs have criticised it. On 14 November, former minister Jacob Rees-Mogg tweeted: "Mystic Meg's predictions are more accurate."

How much faith should we put in its forecasts?

What do we use forecasts for?

Forecasts give a guide to what is most likely to happen in the future.

They are used by businesses to help plan where to invest, and by the Bank of England to guide its decisions on interest rates.

The OBR makes forecasts to check whether the government's spending plans are more likely than not to meet certain targets.

Those targets, set by the government rather than the OBR, are about how spending will look in three or five years' time.

How good are the OBR's forecasts?

The OBR was set up in 2010 by then-Chancellor George Osborne to take the job of marking the government's Budget-day homework out of the Treasury, a government department.

On Thursday, it forecast that the economy would grow by 2.5% over the next three years: a year of recession, a year of recovery and then a year of additional growth.

This is very close to the average predictions of a panel of forecasters who give projections to the Treasury each month.

So how accurate have the OBR's predictions been in the past?

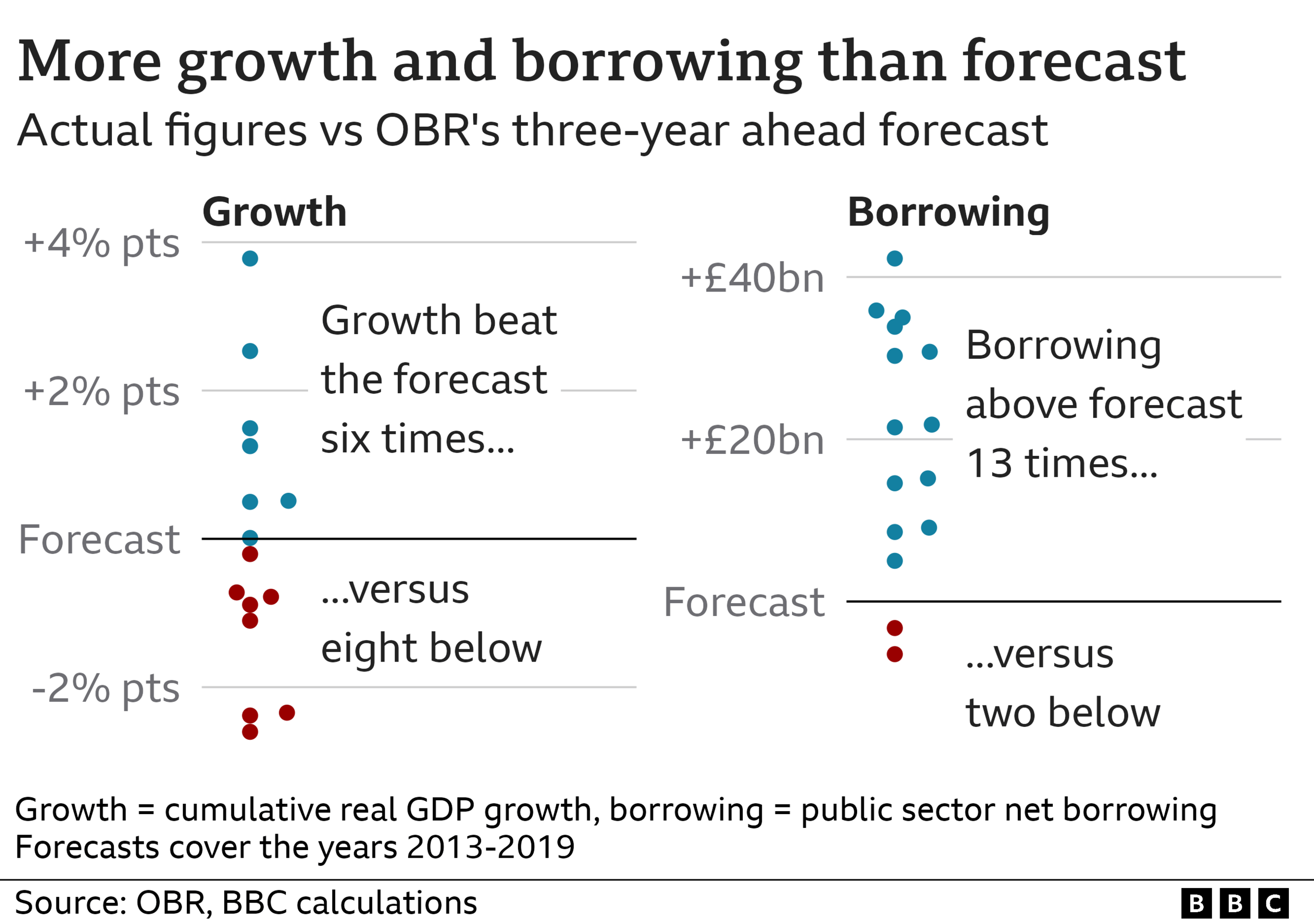

Ten of its 15 pre-pandemic forecasts for growth (shown on the left of the chart below) have been within two percentage points of the economy's eventual growth.

That is slightly better than the margin of error the OBR provides with its forecasts, but two percentage points is still tens of billions of pounds for an economy the size of the UK's.

The chart also shows that actual growth figures have been pretty evenly split between beating OBR expectations (the blue dots) and undershooting them (the red dots).

This is a mixture of short-term pessimism (underestimating the growth in the economy's near future) balanced by longer-term optimism.

The OBR's forecasts for longer-term growth have often turned out to be too positive, largely because the OBR assumed that we would keep getting more productive in the same way we had before the financial crash of 2008. That has not happened.

When it comes to its main job - checking whether the government will live within its means - the OBR has often been optimistic.

The right-hand panel of the chart shows that government borrowing has, more often than not, been higher than forecast by the OBR.

"These things are incredibly uncertain," says Torsten Bell, who worked on economic forecasts in the Treasury before the OBR came into being, but argues "this system is definitely better" than the one it replaced.

How does the OBR compare with other forecasters in the UK?

The OBR has one big constraint that affects no other forecaster. By law, it has to believe everything the government says.

If the government says "we'll raise fuel duty next year" or "furlough will end in October", other forecasters can take account of the possibility those plans might change. The OBR cannot.

Despite this, the accuracy of the OBR's forecasts for the size of the economy this year or next look slightly better than average, when compared with others in the Treasury's monthly collection of forecasts. They are also pretty close to that of the consensus.

And the OBR has advantages over others when forecasting government finances - privileged access to data from government departments.

That makes its forecasts a "benchmark" for others looking at the impact of policy on the UK's finances, says Sonali Punhani, an economic forecaster at investment bank Credit Suisse.

How do the UK's forecasts compare?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) says that the forecasts it makes for growth the following year in most advanced economies like the UK's have, more often than not, been within about 1.5 percentage points of what actually happens.

The OBR's forecast confidence and performance is within that range.

But spotting recessions and rebounds in advance, just like spotting pandemics, is much harder.

The IMF's forecasts picked up fewer than 10% of recessions a year ahead of time (and just over half early in the year of the recession itself), according to an analysis it conducted of recessions around the world between 1992 and 2014.

What is the best way to read a forecast?

All this uncertainty makes league tables of forecast growth years in the future hard to believe.

You might feel comfortable saying "Manchester City will still be competing for the title in two years", but still stop short of predicting where exactly they will finish.

The professionals "obsess less about the exact figures than the story they help to tell", says Ms Punhani, "running different forecasts to see how things might change under different circumstances".

The OBR's report identifies the war in Ukraine, international gas prices and the cost of government debt as the biggest sources of uncertainty in its forecast.

Moves in any of those could make the world look very different to forecasts today.

You can also compare different forecasters, working out why they are different and what that says about the economy.

For example, the OBR's projections are more optimistic for the UK's economy than the Bank of England's, as the OBR assumes that people will dip further into their savings in the next year or two.

But neither suggest that the next few years will be easy.

Related topics

- Published17 November 2022