Hepatitis C diagnosis 'like a death sentence'

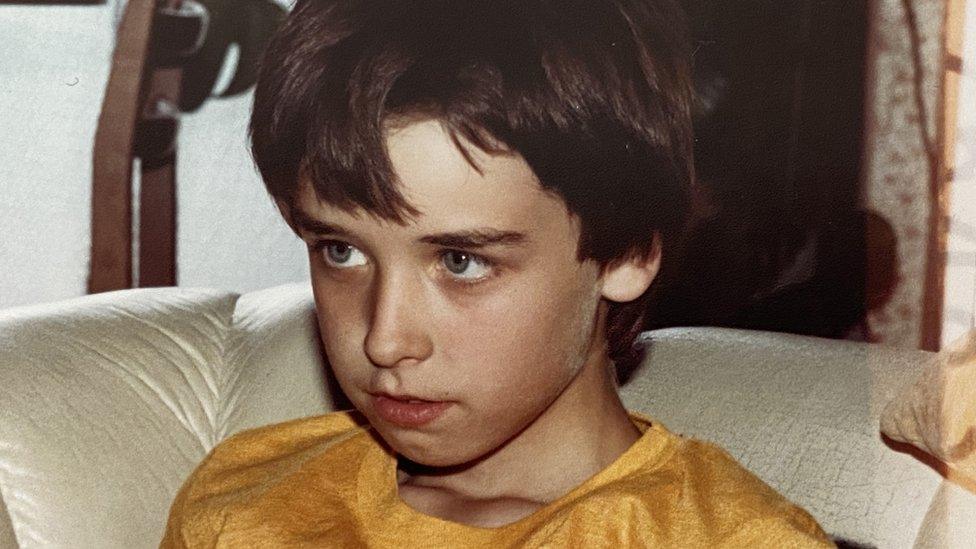

Ms Busby says those affected by the infected blood scandal deserve justice

- Published

A woman who contracted hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood during a transfusion more than 50 years ago says she feels like her life "has been stolen".

Hazel Busby, 73, says the ordeal continues to affect her daily life because she has to deal with the painful after-effects of medication she was prescribed to treat the illness.

More than 30,000 people were infected with HIV and hepatitis C during the infected blood scandal scandal, when NHS patients were given contaminated products between 1970 and 1991.

Two main groups were affected – haemophiliacs and those with similar disorders, and those who had transfusions after childbirth, surgery and other treatments.

'A nightmare'

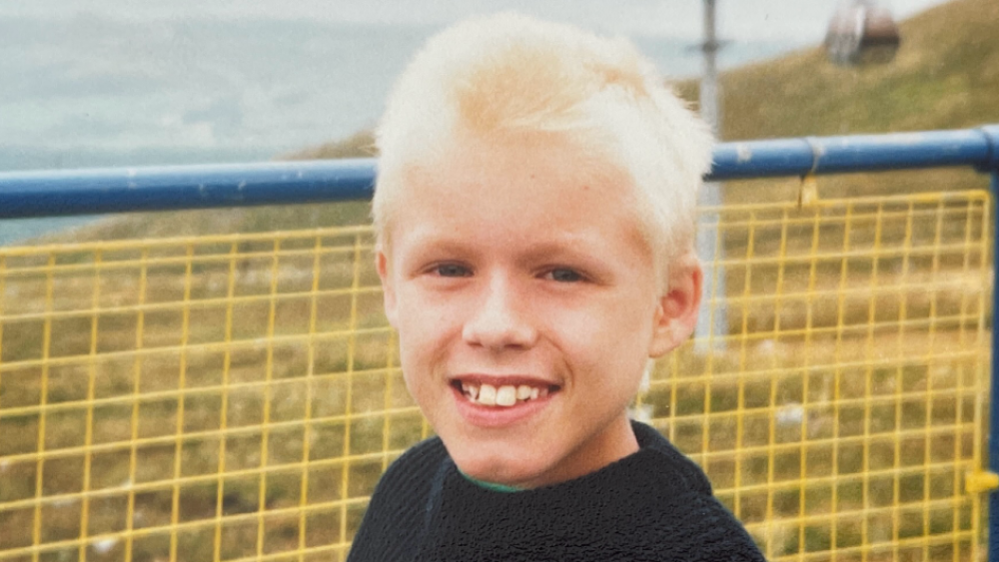

In 1971, Ms Busby, from Street, Somerset, was just 20 when she underwent a blood transfusion following preventable complications during the birth of her son.

"The whole thing was a nightmare because I was left on my own," she said.

"I ended up delivering my own son, as his head was coming out.

"I was overjoyed, I'd got this little boy, I was so happy dancing around, and then I passed clean out. They discovered I needed two pints of blood."

It was not until 2006 that Ms Busby learned the terrifying truth of what had happened to her.

After noticing some unusual symptoms she visited her doctor who carried out blood tests. She was later diagnosed with hepatitis C.

"It was like a death sentence," she said.

Ms Busby was successfully treated for hepatitis C with interferon treatment, but it has led to her developing type 2 diabetes and severe mobility problems.

Hazel Busby says she is "still suffering" from the after effects of the scandal

In total, it is thought about 2,900 people have died as a result of the scandal.

The findings of a public inquiry, external into what has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history are due to be published next month.

Victims are campaigning for compensation but the government has said it would be inappropriate to comment until the inquiry's full findings have been published.

Ms Busby's overall health continues to decline.

"I have never felt so ill on a daily basis, ever. I can't even walk around anymore, only for a few yards," she said.

"Sometimes you're very low, but there are other times when you feel really angry.

"I'm angry that my life's been stolen and I can never get it back.

"This should never have happened," she said.

Ms Busby says her infection also caused estrangement from some family members due to the stigma.

"If anybody hears you mention hepatitis C they jump back," she continued.

"You're looked at like you're dirty, or accused of being a drug addict.

"I'll go to my death feeling that stigma, of being unclean somehow, or not right."

Hazel Busby contracted hepatitis C after receiving a blood transfusion in 1971

'We want justice'

Ms Busby is just one of tens of thousands of people campaigning for compensation, having been "spurned and shunned" for much of her adult entire life.

"I just feel angry in general at the whole thing, you can't pin it on anybody," she said.

"But it does need people that are in charge now to compensate us properly and do the right thing. We're all suffering so much.

"I would like them to pay up. We want justice, for it to be put in every newspaper and on the TV, for the truth to be spoken about," Ms Busby continued.

"A giant, enormous apology for everything they've done to us, and everything they've tried to back away from and pretend it never happened."

Those infected have received annual financial support from the government, but a final compensation deal has not yet been agreed.

The government said it would be "inappropriate" to consider final compensation payments ahead of the inquiry's full report.

A government spokesperson said: "This was an appalling tragedy, and our thoughts remain with all those impacted."

They added the government had consistently accepted the moral case for compensation.

"We will continue to listen carefully to those infected and affected about how we address this dreadful scandal."

- Published22 April 2024

- Published3 February 2023

- Published21 June 2021

- Published6 October 2022