Miners' strike divisions 'have never gone away'

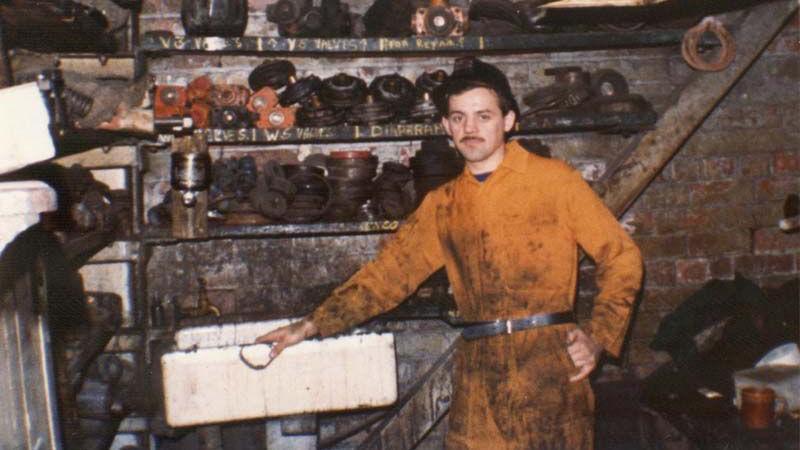

Rab Wilson at Barony Colliery near Auchinleck in 1983

- Published

Memories of throwing stones at "scabs", soup kitchens, and Arthur Scargill rallies during the miners' strike remain, for many, as fresh as ever 40 years on.

For mine workers at the heart of the industrial action in 1984-85 across south-west Scotland it was a life-defining time, as thousands across the region downed tools for a year.

They risked not being able to put food on the table amid fears that Margaret Thatcher's government, backed by the National Coal Board (NCB), wanted to destroy the industry.

But the government said the industry was running at a loss and change was inevitable.

Rab Wilson kept a diary during the miners' strike

Widely regarded as one of the most bitter industrial disputes in Britain, and the largest since the 1926 general strike, it had a massive impact for many.

Communities across Ayrshire and Dumfries and Galloway were dominated for generations by coal mining.

And New Cumnock, Sanquhar, Kirkconnel and many others have lived in the shadow of the upheaval and loss of industry ever since.

Rab Wilson gave up mining due to the "pain and damage" of seeing the Thatcher government "break the back of the unions".

He fervently believes history proved Arthur Scargill and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) were right in believing ministers had secret plans to close more than 70 pits.

It was 'divide and conquer'

The ex-mine engineer, from New Cumnock, kept a daily diary throughout the strikes, and said: "There was a great deal of divide and conquer by the government, where they encouraged struggling miners back to work.

"It caused a great deal of animosity here and in surrounding villages - Cumnock, Auchinleck, Muirkirk, Dalmellington. They were all severely affected, suffering dreadful economic hardship.

"I remember individuals being targeted, their house windows being smashed and almost riot-type behaviour going on across the district."

It was a life-changing time for the 63-year-old, who then gave up the pits after seven years and trained as a psychiatric nurse in Dumfries.

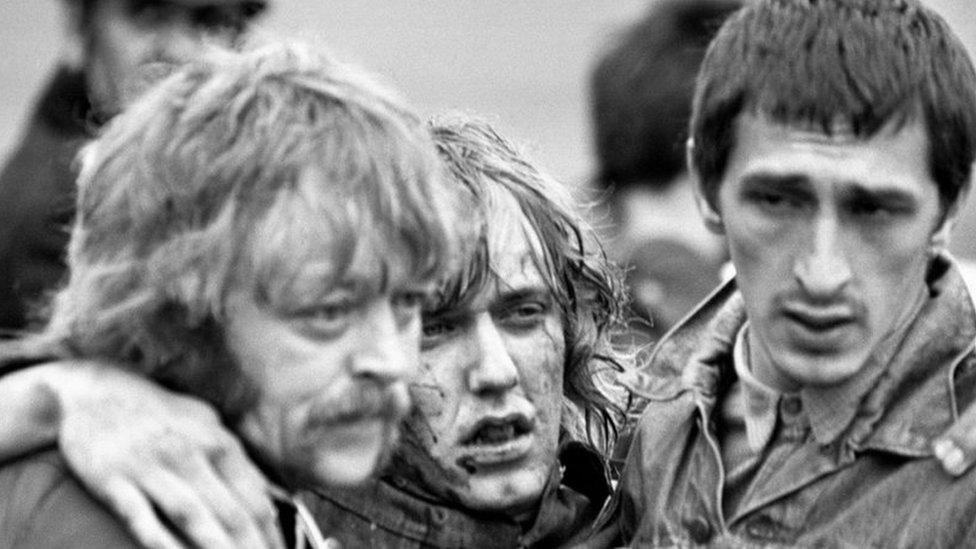

Miners at the Barony Colliery near Auchinleck in 1983

Rab, who was 23 at the time, "doesn't have any regrets" about being on strike for a year.

He added: "We've since found out there was a secret plan by Nicholas Ridley and Thatcher against the mines."

He was in a few silver bands, attended Scargill's rallies and vividly recalls "going around the soup kitchens at Sanquhar, at Kello Rovers, and all the towns to show support".

On the strike's outcome, he adds: "I went back to work a week before the end of the strike, so had to drive through those gates and cage buses, which wasn't fun.

"Within a few years all the collieries closed, and that way of life, that culture, which was a big part of lowland Scotland, was completely eradicated.

Strikers from Barony Colliery near Auchinleck in 1984

"Did it do any good? I look around here in East Ayrshire and it still is an economically-deprived area. Thousands were employed through the pits, that's gone and not replaced."

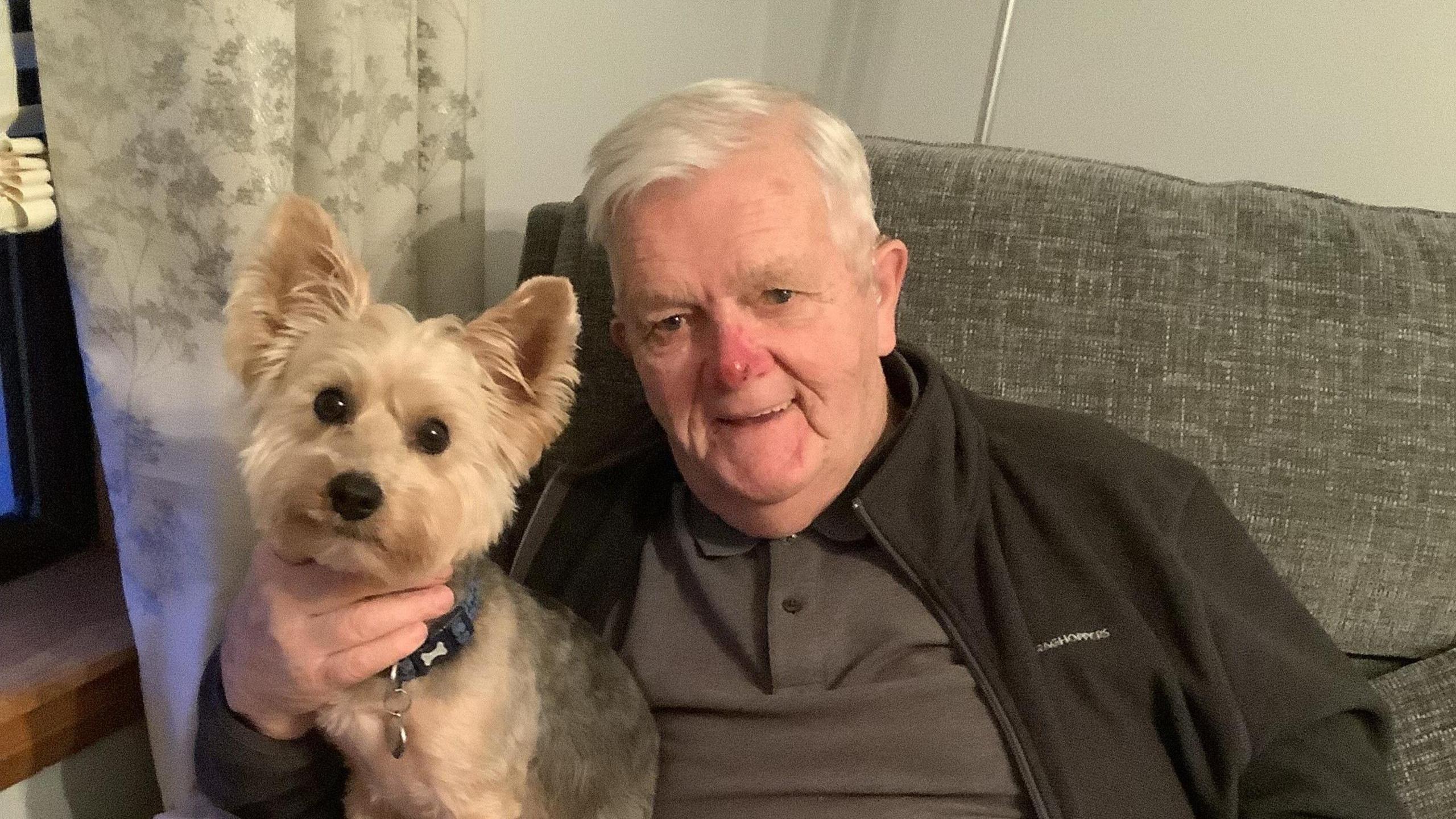

Jim Campbell was 44 when the strike began, and spent a year struggling to make ends meet with his three sons also being on strike.

The 84-year-old from Kirkconnel is a staunch believer that while striking was the right thing to do, Scargill made a fatal error.

"Scargill should have called a vote, that's where he went wrong, but sadly he was too arrogant," he said.

Rab Wilson at Barony Colliery near Auchinleck in 1983

Jim had spent stints at three different mines from 1954, and feels the miners strike was "the toughest time".

He said: "We were all living together, none of my sons were married then. Only my wife was working but we had to pay full rent, so it was hard, very hard.

"This village is surrounded by coal. During the strike my sons went to the banks of Kello Water near here, which is full of coal, and they went and dug out coal from the hillside to make some money.

"It was dangerous, I couldn't because when I was 20-years-old I was trapped by the legs in Fauldhead Colliery for two-and-a-half hours which led to my osteoarthritis."

Jim Campbell was on strike with his three sons

Jim's family were heavily active as the community pulled together during the strike.

His son Ian was at the Battle of Orgreave in South Yorkshire, where strikers clashed with police, and Jim's sisters helped out at the nearby Kello Rovers soup kitchen.

Alastair Monteith remembers the miners strike as "a harrowing time" which led to lifelong divisions between friends and family.

The 70-year-old grew up in a mining family, with his father and brother also working in the pits, and became a joiner after the collieries closed.

Roger Mine in Kirkconnel closed in 1980, before the miners' strike

Alastair said: "I remember there was a particular higher spot overlooking a bridge here in Kirkconnel where strikers stood to throw rocks at the buses ferrying workers in.

"People refused to associate with the local bus companies as well. The divisions ran really deep and they've never gone away.

"It was a horrific time, I remember a lot of people chopping down trees to sell wood just so they could afford to eat."

Alastair recalled a lot of people moved away, leading to some "special reunions" in recent years.

But he said that Kirkconnel "shrunk in only a few years" as derelict buildings were pulled down.

He added: "It was really sad. The damage of losing the mines has lasted".

Follow the BBC for the South of Scotland on X, external.

Listen to news for Dumfries and Galloway on BBC Sounds.

Get in touch

What stories would you like BBC News to cover from the south of Scotland?

- Published2 March 2024