'It gave us hope, then shattered our lives'

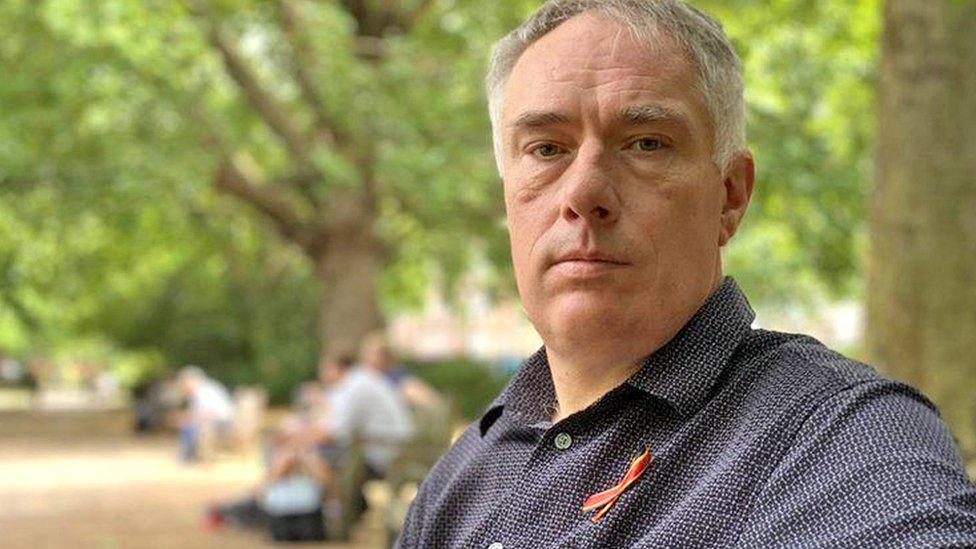

Suresh with his brother Praful

- Published

Thousands of people in the UK were given contaminated blood products during the 1970s and 1980s. Will a public inquiry deliver justice for the victims?

In the late 70s, teenagers Suresh and Praful Vaghela felt they had a bright future ahead of them.

The brothers had just started an exciting new chapter in their lives, enrolling at college.

Both haemophiliacs, they had also been undergoing a revolutionary new treatment which had drastically improved their quality of life.

But this apparent "magic bullet" for their health problems soon unravelled into tragedy, as they found themselves engulfed in one of the UK's biggest health scandals.

Imported blood

Suresh and Praful had been haemophiliacs from birth. The inherited disorder prevents blood clotting properly and can lead to spontaneous bleeding.

The new treatment - known as Factor VIII - came as welcome news.

Factor VIII is a clotting agent which people with haemophilia A have a shortage of, external.

During the 1970s, a process was developed to replace the missing agent, made from donated human blood plasma.

But the UK was struggling to meet demand for blood-clotting treatments, so imported supplies from the US.

"They said we have a magic bullet, it's going to improve your life tremendously and it did, but none of the side effects or possible side effects - or where [the plasma] came from - were shared," says Suresh.

The young brothers pictured with a former teacher

Once the new treatment was available, instead of spending weeks recovering after a "bleed", Suresh and Praful could take Factor VIII at home, and be back on their feet within hours.

It was a huge relief and for a while made an incalculable difference to their lives.

However, in 1980 - while at college - Suresh fell ill.

"I was quarantined in a room, I couldn't leave it, I wouldn't be allowed to talk to anybody, [everything] coming in was washed and sterilised.

At that point, Suresh thought the symptoms were a side effect of his haemophilia, but now realises he had hepatitis C.

He also believes doctors were aware of how he might have been infected, but withheld it from him.

Suresh continued his life as normal. Whenever he became ill, he continued to assume it was due to his haemophilia.

But in 1983, he had a phone call from a doctor, who told him he was HIV positive.

"It was an absolute bombshell because my life just shattered within seconds.

"I asked them what do I need to prepare and they said, just go home, tell your family, you've got three months, just get your papers in order.

"There was no medication, you've got three months to say goodbye."

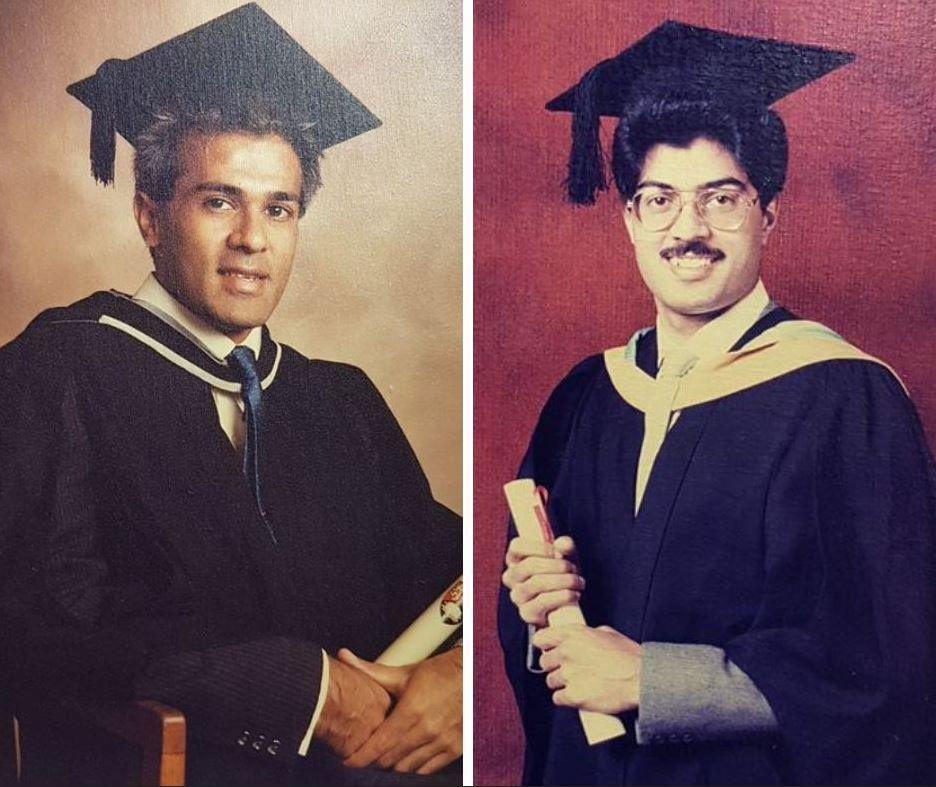

Suresh and Praful at their graduations

Suresh says that at the time, the question of how he contracted HIV wasn't foremost in his mind.

"They said it was from the treatment. I knew it must have been from the treatment as it was the only medicine I was having. They didn’t explain why it had it in or where it came from.

"I can’t remember what I thought. My main thought was 'I have HIV' not about where it came from.

"I guess I thought well the treatment is from hospital, so I don’t know why, but I never questioned it."

He says he was told to carry on taking Factor VIII.

After his diagnosis, Suresh's life had severe limitations.

“I wouldn’t go to any end-of-term balls. I didn’t go to parties, I didn’t go to functions. I didn’t out of fear I would be spreading it. You constantly lived in fear.”

When three months had passed, Suresh thought he wouldn't wake up the next day, but he did.

He attended doctors' appointments every few weeks, but as he remained healthy, the visits became less frequent.

He says the doctors told him they weren't sure how he was still alive.

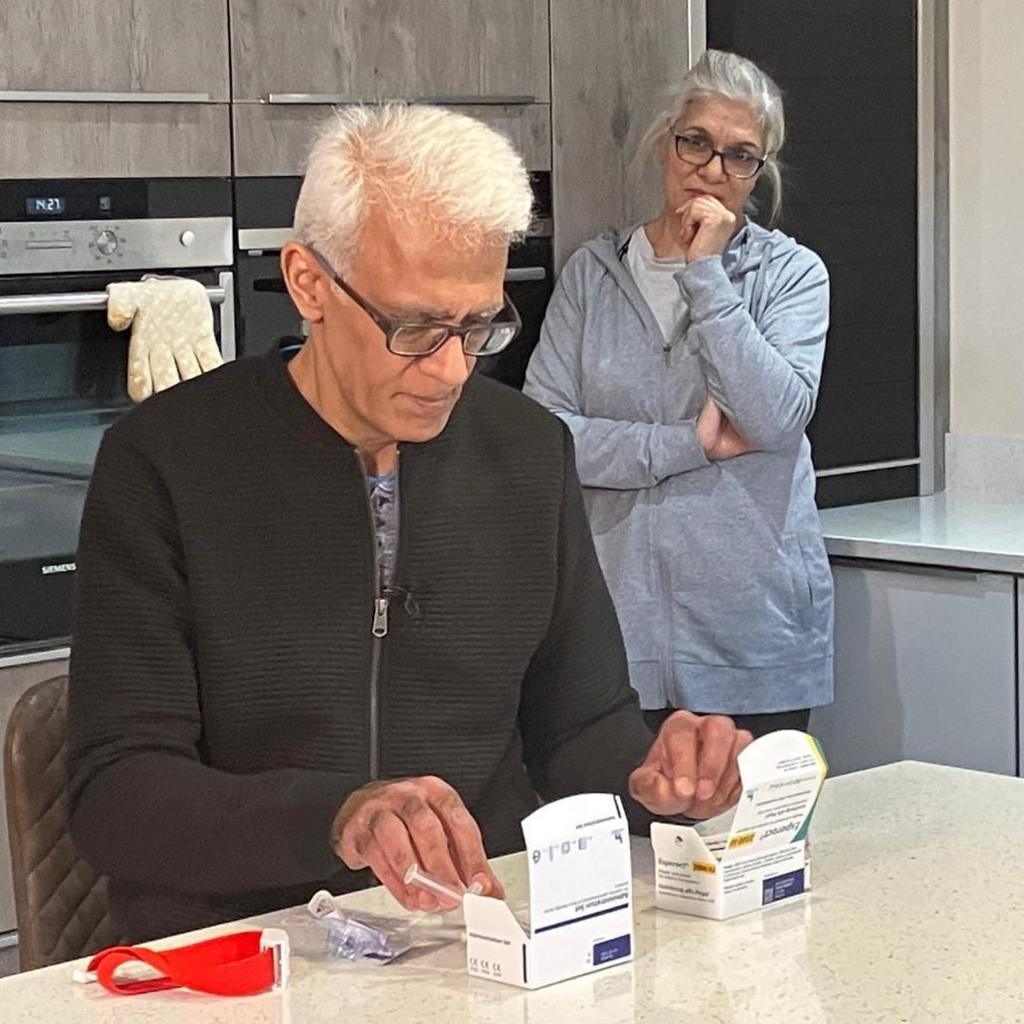

Suresh and his wife Rekha

In 1988, Suresh met Rekha.

They are now happily married and living in Leicester, but because of Suresh's health problems did not have children.

He has continued to suffer from the effects of HIV and hepatitis, and has undergone many different treatments, including, in 1991, interferon injections for managing his symptoms.

The therapy had a severe impact on his health, leading to massive weight loss and memory problems.

In July 1995, Suresh's brother Praful died from Aids - he was only 33.

He too had contracted HIV from contaminated Factor VIII.

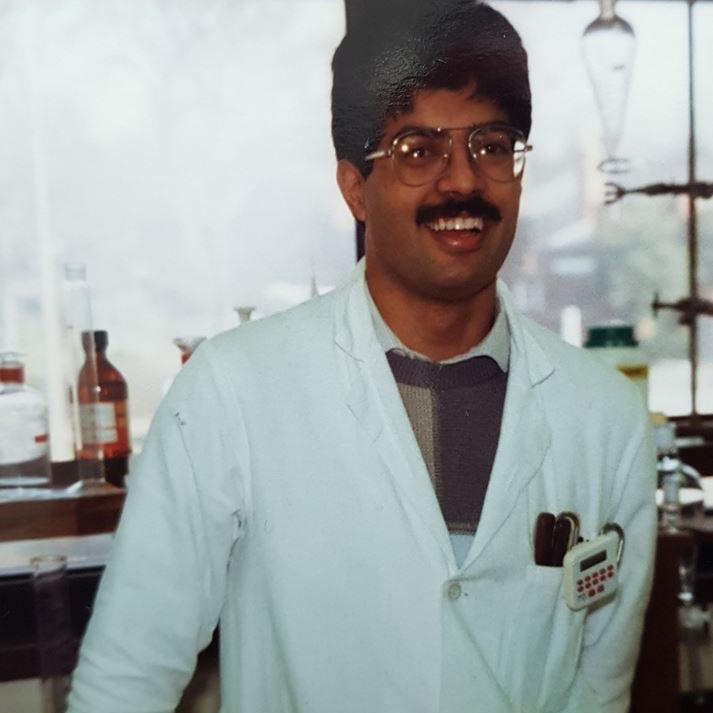

Praful, like many other haemophiliacs given infected blood, died of Aids

"It was one of the worst times of one's life because he was my brother, he was my mentor, my support, and you learn from your older brother. And just at the point where we would be sharing a life together, he was taken away."

"He died a terrible death in the sense that he was at the hospital and he was going through the worst of infections. And we just had to watch him deteriorate day by day - he just couldn't get out of his bed, sit up, stand up," says Suresh.

Prafel died in Sussex - at the only Aids hospice available to him at the time - far away from his family in Preston.

"By the time they got hold of us and we got there, he had already passed away."

Suresh has to take 12 tablets per day to manage his health conditions, including HIV

Sadly, many of Suresh's friends in the haemophiliac community also died of the disease over the years.

"The loss that we've all gone through is phenomenal and my personal loss has been great because we're all part of a family and you feel that you're going to be next," he says.

"When you've been to 70 funerals in a year it just drains you, you just haven't got the energy, you haven't got what it takes just to survive."

In June 2005, Suresh was also told he was one of the recipients of a batch of Factor VIII which was infected with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).

The infected blood scandal

The scandal sparked protests, with campaigners demanding answers for those affected

The Factor VIII treatment was manufactured by pooling plasma from tens of thousands of people.

Much of the blood bought from the US was from high-risk donors such as prison inmates and drug users.

If just one was carrying a virus, the entire batch could be contaminated.

More than 30,000 people in the UK were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood products during the 1970s and 1980s.

A public inquiry into what has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history will announce its findings in May.

Suresh and the hundreds of other families affected say they want answers.

"These past 40 years the whole of my life has revolved around hepatitis C, HIV and the ones who died, they have been everything from the start of the day till the end of the day," he says.

"The mission is to get the truth, get the truth which they won't share, get a sense of assurance for the community that this won't happen again.

"I want the government to accept that they've done something wrong."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on X, external, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to eastmidlandsinvestigationsteam@bbc.co.uk, externalor via WhatsApp, external on 0808 100 2210.

Related topics

- Published28 February 2024

- Published9 November 2022

- Published29 July 2022

- Published23 February 2024

- Published8 February 2024

- Published17 January 2024