On a terraced street in Middlesbrough, a teenager in a mask takes out a long kitchen knife from his trousers and says he’s prepared to use it. “It’s brutal round here, you have to be prepared, if you don’t stab them, they will stab you.”

He is part of a group of young drug dealers, and I have no reason to doubt him. One of them says he was 14 when he started. Why? Money - they talk openly about how much they can make from selling heroin and crack cocaine.

As if to emphasise the point, another in the group holds up small bags of white rocks, which he says are crack cocaine. They charge £10 a bag and say they can sell hundreds of bags every week.

“No-one is going to change it, the bobbies can’t change it,” one of the dealers says.

Watch: Teenage drug dealers and local residents tell Ed Thomas what crime means for their daily life

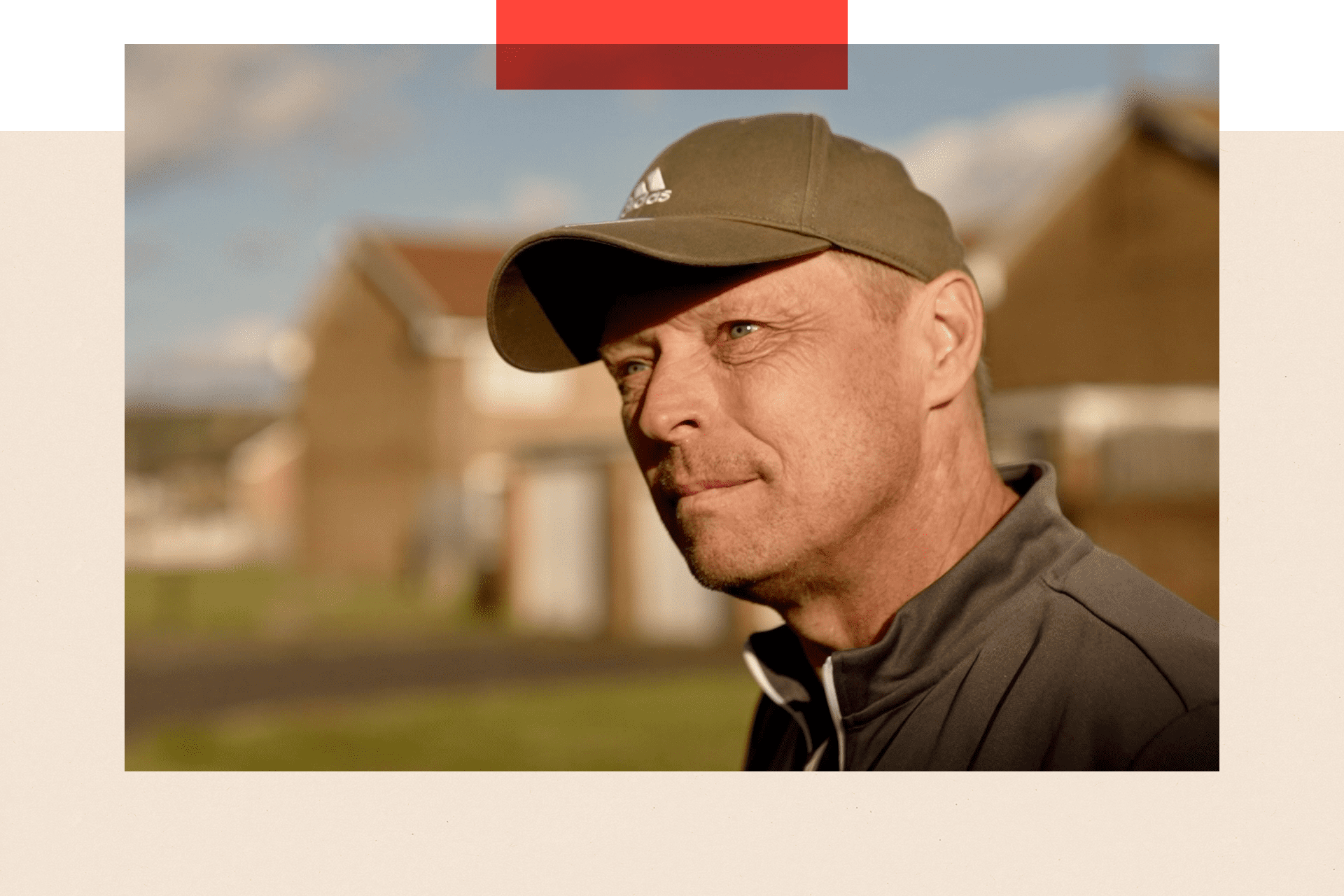

Wherever we went in Middlesbrough, people wanted to talk about the impact of drugs. On the Netherfields estate, we met Tony, proud to be from the town.

“I’ll show you something, we call it the penthouse,” he says excitedly. He shows me a small block of flats where nearly every window has been smashed out or boarded up.

And it’s not just the one - many more homes here have been vandalised and smashed. Tony is incandescent: “It’s degrading, we feel like a waste of space, like we’re non-existent.”

The demand for drugs is high. In 2022, the government estimated that there were more than 300,000 people dependent on heroin and crack cocaine in England. And between them, they were responsible for nearly half of all burglaries, robberies, and other acquisitive crime, like shoplifting.

The statistics show that both the number of crimes recorded and the rate of crime has increased since before the pandemic, even if police say recorded crime (excluding fraud) fell by 1% in 2023 in England and Wales compared with the year before. Separately, the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggests that excluding fraud and computer misuse, crime has been steadily dropping since 2010.

Tony says it feels like people where he lives don't matter

It's a complex picture, but contributions to the BBC’s Your Voice, Your Vote project told us that for many people, crime is a major issue that they want the politicians to fix. So we came to Middlesbrough to hear people’s experience of it here.

To many people who live in Middlesbrough, it certainly doesn’t feel like crime is falling. Last year, Cleveland police recorded the highest overall crime rate out of all forces in England and Wales, affecting 137 out of every 1,000 people.

I spent three days here, and found that crime numbers don’t tell the full story of what’s happening in communities like North Ormesby, who are desperate for help.

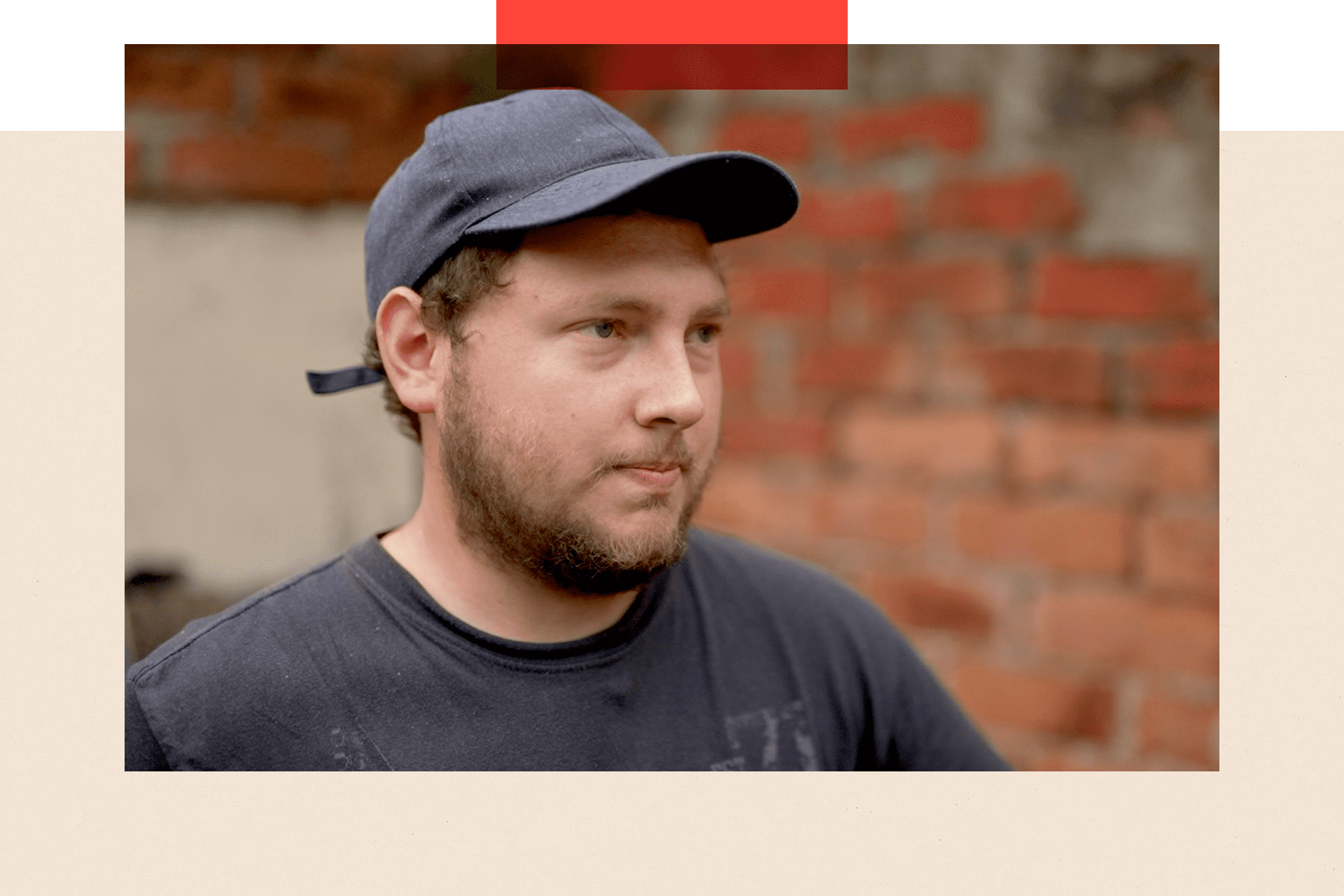

Aidan is in his 20s and has a young family to support. He works hard in a restaurant, grabbing every hour offered and he’s also set up his own business as a handyman. He says he sometimes works over 70 hours a week.

As we walk and talk, someone shouts “welcome to Beirut!“ Aidan says he’s desperate to succeed but admits to being scared in the place he calls home. He takes us to one street with about 50 homes, and we walk past smashed windows, boarded up windows, and homes with obscenities sprayed on the walls in red paint. He reckons that on this one street, about 20 homes have been burgled over the past four years.

Officially, fewer people are being burgled. The Crime Survey for England and Wales suggests that there are less than a fifth of the number of burglaries that there were back in 1995. But in 2023, Cleveland police recorded the second highest rate of theft and the second highest rate of violence against a person.

Aidan says he feels he pays more in taxes but is getting less back

What Aidan says next explains a lot of the despair that people feel. “We’ve been burgled, the police never came out, all I got was a crime reference number.

“I’m paying more council tax, energy bills and rent than ever before but the services I’m getting back have decreased.”

The most recent annual Home Office data says that in the year to March 2023, fewer than 4% of burglary offences in England and Wales resulted in a charge, albeit this was up on the previous year. In North Ormesby, the part of Middlesbrough where Aidan lives, around 95 in every 100 crimes last year went unsolved.

Cleveland police say they’ve taken a proactive approach in Netherfields, imposing five dispersal orders and have arrested children as young as 12. CCTV now covers the estate and people here say the anti-social behaviour issues with teenagers is calming down. In North Ormesby and across the region, police say they are working closely with people in the community and working with multiple local agencies.

But in late 2022, the UK’s then lead for neighbourhood policing said officers were spending too much time taking care of social problems, and not enough on tackling crime. Chief Constable Olivia Pinkney, now retired, said officers could spend half their shifts working on behalf of other services.

She said it meant that victims were being failed and the criminal justice system was in crisis.

Boarded-up windows are common in these parts of Middlesbrough

In North Ormesby we came across a classic example - a police van attending what we thought was an emergency call, only to realise it was a welfare check for a vulnerable woman called Kimberley.

“They’re not just here to help, they’re helping with the mental health. I’m ADHD, bipolar and emotional stability disorder,” she told us. “They’re really nice and they’ll sit with you and make you feel good.”

Less than half a mile away, on Kings Road, there is a parade of shops where locals told us there were thefts most days. It’s got so bad that the Candy Corner shop at the end of the road has started naming and shaming those accused of shoplifting, hanging a large canvas poster with their faces on it outside the shop. Under the faces it reads: “Steal from the shop and you will be our advert outside the shop for six months like these idiots.”

While we were on Kings Road, a group of five men stormed the supermarket, some with their faces covered. They were in and out in seconds and what did they steal? Chocolate bars.

Facing them behind the till was Ellie. “It was scary them coming in. I thought they were gonna take money,” she said. “It’s just the usual, every day,” she adds.

Ellie said the police usually only turn up if it happens a few times in a day. Speaking to her, it’s hard to believe anyone can be so accustomed to crime.

Shoplifting is up, especially in deprived areas. Offences recorded by police in England and Wales have risen to their highest level in 20 years.

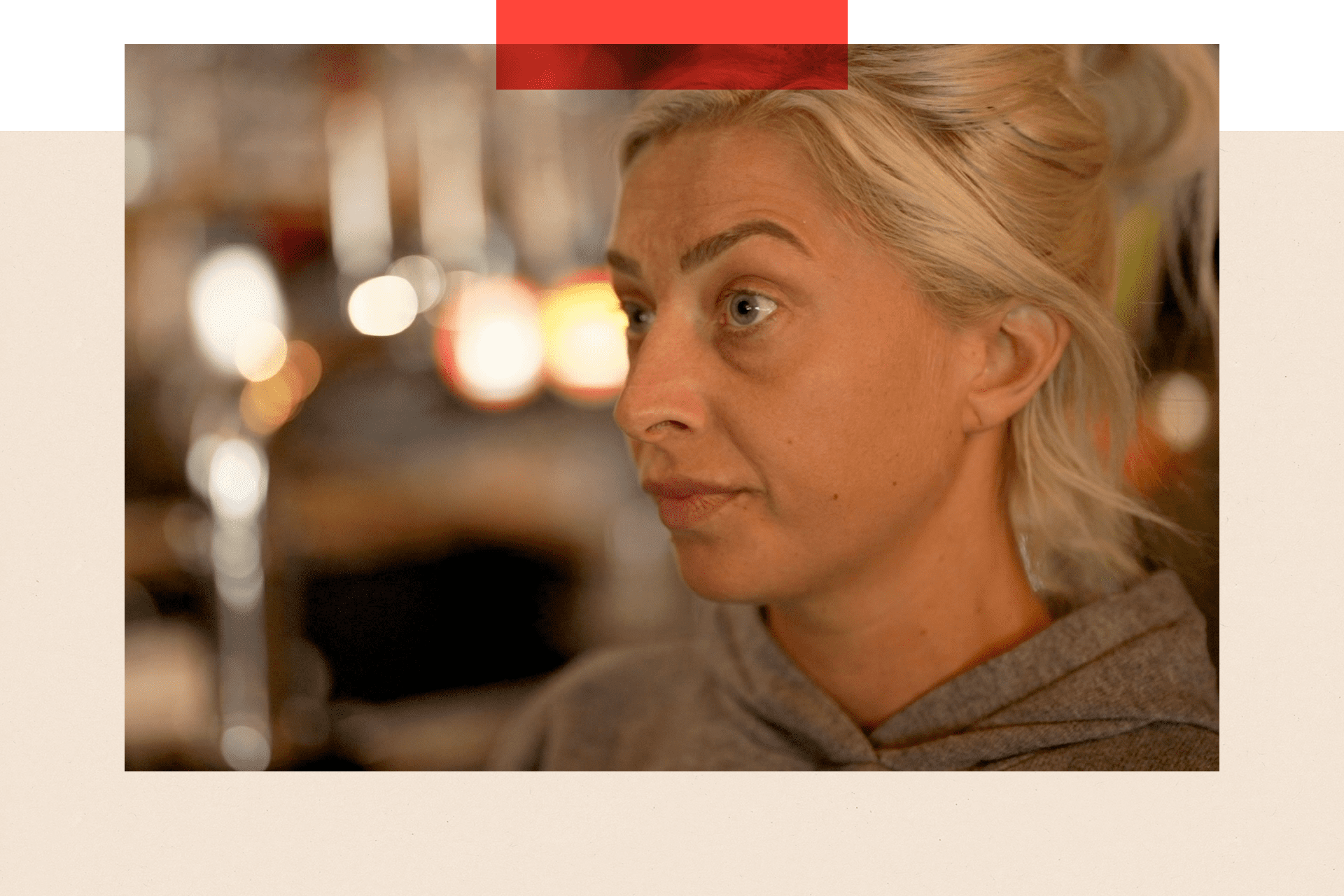

Sarah has seen her bar repeatedly targeted by burglars

More than 430,000 offences were recorded last year - up by more than a third compared with the previous 12 months to December 2022, according to the police figures.

Nearby we met a business owner who said they had started slapping thieves who tried to steal from their shop. They wanted to remain anonymous, but showed me CCTV of one incident. They said they feared that they couldn’t rely on police, so preferred to take matters in their own hands. When I asked about the risk of arrest, they said it was a risk worth taking to protect their livelihood.

Others are taking desperate measures too. Sarah, who runs Legends Bar in the town, says the bar has been targeted five times in two years, and shows us CCTV from the last break in. “You can see where they pulled the shutters, they tipped over a fruit machine worth thousands of pounds. They’ve done a lot of damage, it makes you feel sick.”

More from InDepth

What's the real distance between Sunak and Starmer on climate?

- Published11 June 2024

Who owns the Moon? A new space race means it could be up for grabs

- Published9 June 2024

Will coalition turn domineering Modi into a humbler leader?

- Published9 June 2024

On that occasion, thieves stole two bottles of vodka and the Christmas tip jar. Sarah doesn't know of anyone being prosecuted for the thefts or damage at her bar, and on some occasions no longer claims on her insurance. She says crime is her number one issue this election.

“One day they came in and nicked my KP Nuts. Nuts! It’s horrendous.” She says she has started sleeping in the bar overnight sometimes, and has turned to Facebook to try to solve the crimes, and even offered rewards with her own money.

“Next time do I even ring the police? Do I just leave it? It can’t keep going on like this.”

Later I meet Meela outside her home, chatting with neighbours in Netherfields.

“As soon as I’m out of this area I’m a different person,” Meela says. “As soon as I get to the roundabout coming in, I get anxiety."

I ask her whether politics can fix this. No, she says. “It’s the drugs, people need to knock down the drugs.”

In just England alone there is a lot to fix. An independent review conducted for the government by Dame Carol Black in 2021 said drug misuse costs society almost £20bn a year, which is close to £350 for every man, woman, and child in England.

That means even if you’ll never visit Middlesbrough in your life, illegal drug dealing does impact on your life. When public spending on services we all need is tight, money spent on drug misuse is cash that is missing from other vital services.

Back in North Ormesby I wondered what this general election means to the teenage drug dealers, who tell me they are old enough to vote. One says they don’t know what it is all about. I also ask, if politicians say they want to crack down on drug dealing, what would you say to them? “Catch me if you can,” one says, and then they all start to laugh.

Is this all they want from life I ask? They are after all just teenagers. One of them takes time to answer. “I don’t want to sell drugs, for the rest of my life, no one does, it’s just how it is," he says.

Nationally, crime is not the biggest election issue. Concerns around the cost of living, the NHS, the economy and immigration all poll higher.

But in places like North Ormesby and Netherfields concerns about crime are very real. People are desperate for help. Before we leave, Tony tells me: “Whoever wins the next election needs to step up to the mark, this cannot continue.”

What really matters to you in this general election? What is the one issue that will influence your vote? Click the button below to submit your idea, and it could be featured on the BBC.