The ancient lagoon that keeps us safe on icy roads

Supplies of rock salt from Cheshire keep the UK's roads running during freezing conditions

- Published

While gritters may be a familiar sight across the country over winter, the ancient source of the salt which keeps us safe on the roads is perhaps less well known.

Most of the country's road salt - and all of its rock salt - comes from Cheshire, where rich reserves have been extracted since prehistoric times.

Cheshire's salt mines date back to the Triassic geological period, some 220 million years ago, when the county's weather was very different to what it is today.

The importance of salt to Cheshire is shown in the names of towns like Northwich and Middlewich, where the 'wich' suffix means salt-making town, derived from Old English.

How did Cheshire come to be the UK's home of salt?

Liz Montgomery from West Cheshire Museums service said the county's rich salt reserves dated back to prehistoric times, when the county was hot, dry and arid.

She said: "Cheshire used to be near the equator and there was this big tropical salt water lagoon in the area and water used to flood in and would then evaporate and then reflood, laying down layers of salt."

Ms Montgomery said this valuable commodity had been prized by Iron Age settlers as well as Romans.

"If a town has got 'wich' at the end of its name, such as Northwich and Nantwich, then this used to be 'wic', which developed into 'wich', and which means 'salt town'," she said.

Ms Montgomery said that during the Iron Age water from the lagoon which bubbled up in brine springs would be collected and boiled in order to harvest salt.

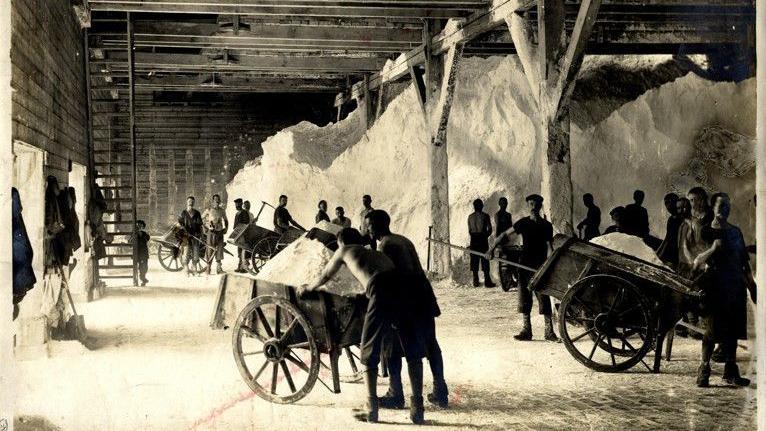

The techniques used to pan for salt has evolved over centuries.

"Roman and Medieval salt pans were made of lead but by the time we get to the 18th and 19th century and into the 20th century there were big iron salt pans," Ms Montgomery said.

'Thirsty work'

The Roman lead salt pans looked like big lead trays, some of which are on display at Lion Salt Works museum in Northwich.

Salt pans only changed in appearance around the 19th century, with salt still being sourced at the Lion Salt Works up until the 1960s.

Salt was extracted from water pumped from underground rather than via mining work at the Lion Salt Works.

Some historians believe the importance of the salt industry to Cheshire over the years could be behind the siting of ancient castles and hill forts such as Beeston Castle, Ms Montgomery said.

These castles designed by the Iron Age elite to help ward off invaders so they could keep the prized salt as a commodity important for trading, she said.

Salt mining played a big role in the growth of towns like Winsford, Cheshire

Archaeologists believe Cheshire's salt led to some Iron Age tribes being just as wealthy as those who hoarded coins in the south of the country.

Ms Montgomery said "salt production was really thirsty work" and so the owners of Lion Salt Works, the Thompson family, even built a pub known as The Red Lion Inn on site.

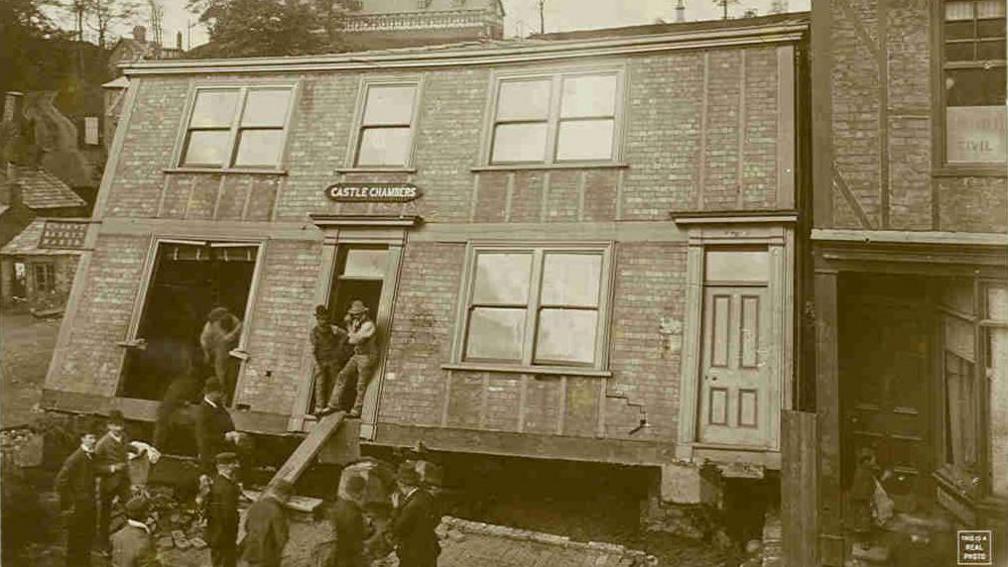

She said there was a wide-ranging impact of salt mining on the communities of Cheshire, including a problem with subsidence caused by Victorian mining practices.

The Victorian practice of flooding beneath the ground to collect salt led to some problems with subsidence, Liz Montgomery from Cheshire West Museums said

Water would be pumped underground and then collected, leading to "huge amounts of subsidence", with "whole roads vanishing", Ms Montgomery said.

Some former mines around Northwich also sank and were then filled with water, becoming lakes known as "flashes", she added.

The salt works reopened as a museum 10 years ago.

What is the salt used for?

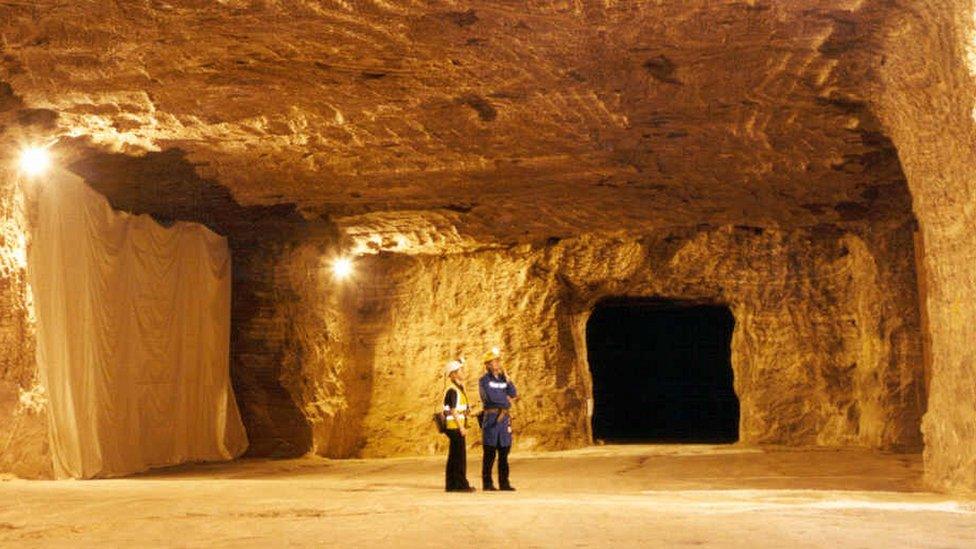

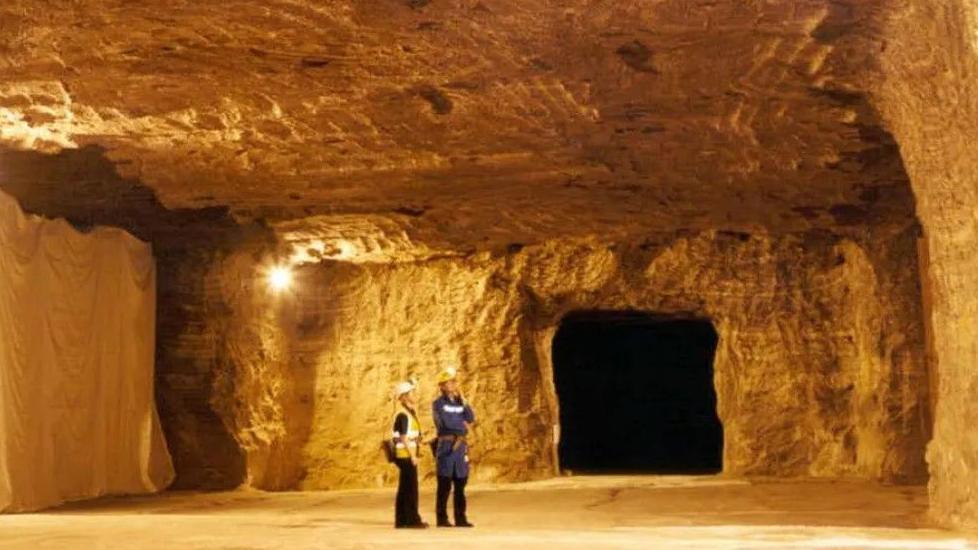

The underground rock salt mine in Winsford, Cheshire, is the country's oldest and biggest working mine.

It opened in 1844 and is now run by Compass Minerals UK, with rock salt being used across the country to keep motorists safe when temperatures fall below zero.

A company spokesperson said that the pillars of rock salt left behind in the mine supported the roof structure.

There are tunnels for access and an estimated 137 miles of space beneath the ground, they added.

Vast caverns like this one in Winsford have been created as salt is mined from beneath the ground

How is the salt mined?

Machines, known as electric-driven continuous miners, claw out walls of salt

This leaves "rooms" or chambers with pillars of rock salt left behind to support the roof

Salt is loaded on to conveyor belts before being crushed and delivered to customers

The vast caverns created by the mineworks have been described by Ms Montgomery as being "a little bit like a weird James Bond-style ghost town", with large machines and buggies used to get around them.

The caverns, said by Compass Minerals UK to be around the size of 700 football pitches, house some of the West Cheshire Museum archives.

Ms Montgomery said she had been told on one visit that the distance she travelled underground to reach them was equivalent to the height of Blackpool Tower.

Compass Minerals UK operates Winsford rock salt mine in Cheshire

Could the salt run out?

The Salt Association, which represents UK salt manufacturers, said that, depending on the severity of the winter, the volume of salt used to grit the roads every year ranged from about three quarters of a million to two million tonnes.

A representative said: "Under normal circumstances this can be met from the three UK mines situated at Winsford, Cleveland and Carrickfergus, although, under extreme conditions, some additional imports may be required.

"There are sufficient reserves of salt under the UK to meet demand for several centuries."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Merseyside on Sounds and follow BBC Merseyside on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external and via Whatsapp to 0808 100 2230.

More like this story

- Published17 February 2016