How a plan to redraw the Irish border fell apart

Three men - Joseph Fisher, Richard Feetham and Eoin MacNeill - were appointed to the Boundary Commission to decide if the position of the border should change

- Published

Border polls, Brexit and political bunfights – the line drawn on the island of Ireland 104 years ago has not stopped making headlines ever since.

But imagine what it would have been like a century ago, when the ink on that line had yet to dry and the exact path of the 310-mile border was still being decided.

You could have been one of those people who opened a newspaper, 100 years ago this week, to find your house was to be pushed from one jurisdiction into the other.

That was the situation many people faced when details of a plan to redraw the border were leaked and published in a English newspaper on 7 November 1925.

The proposals, drawn up by the Irish Boundary Commission, suggested small sections of Northern Ireland should be given to the Irish Free State, and vice versa.

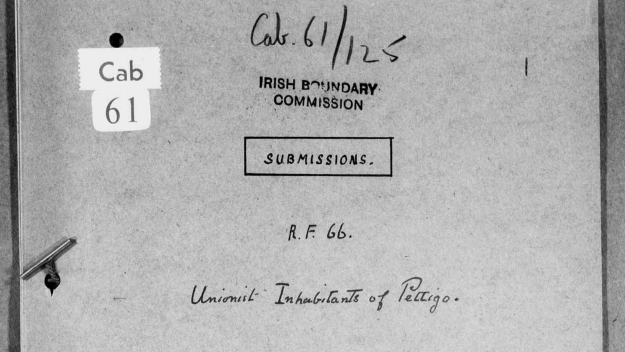

In the end, no changes happened and the border stayed as it was – but the three-man commission, appointed by the British and Irish governments, had spent months gathering views from unionists and nationalists who lived close to the border.

Reading the words of those who spoke to the commissioners gives a sense of how everyday lives were affected during the very early years of partition.

Patrick Cunningham, a farmer and merchant from the County Armagh village of Cullaville, was among northern nationalists who gave personal testimony.

In 1921, the border had cut through his 240-acre farm, leaving most of his land in the neighbouring Free State and cutting him off from local markets and services.

He told the commissioners that Cullaville railway station was "600 yards from my house" but he could no longer use it as it was over the border in County Monaghan.

"My nearest railway station now is Newry, 18 miles away," he complained.

Travelling by road into Free State towns was no easier – customs rules meant people were only permitted to cross the border via certain "approved roads".

"When I start in my motor car from my business premises in Culloville to go to Castleblaney (only 6 miles distance) I am obliged to make a journey of 31 miles to the town of Castleblaney and 31 miles back again," Mr Cunningham said.

Northern Ireland police, including members of the Ulster Special Constabulary, guarding a rural road near the border in the early 1920s

What were the Irish border problems 100 years ago?

Unionists who became reluctant Free State residents faced similar detours, but also complained they had to pay higher taxes and prices than their northern neighbours.

They included County Donegal merchant Thomas Lyttle who had been running his business from the border village of Pettigo for 15 years.

He told the commissioners that Pettigo had been "badly hit" by the loss of northern trade, with customers scared off by customs inspections and fees.

"The inhabitants round about could not come into the town" he said.

"Their baskets were searched and people get excited and would not go in at all. They are buying all at little country shops."

Mr Lyttle also owned a nearby property in Northern Ireland and complained that "every load of hay I want to get across, I have to get a customs form."

The border still runs through the village of Pettigo, with a bridge over Termon River providing access from the Republic of Ireland into Northern Ireland

Customs checks caused problems for people of all social backgrounds, including Major Robert Lyon Moore, president of the County Donegal Protestant Registration Association.

"I cannot get anything through by parcel post from Londonderry under 12 days," he told the commission.

The border ran along the exterior wall of his sprawling estate outside Belleek and it was now affecting his diet.

"If anyone sends me game, I never get it in a fit condition to eat," he fumed.

He also complained about how some packages were taking a circuitous, and expensive, tour through County Donegal before arriving at his door.

"I ordered a pair of boots to be soled in Londonderry the other day.

"They were sent to me to Belleek. From Belleek they had to go to Lifford, which is within 10 miles of Londonderry, to be examined.

"From Lifford they were sent to Ballyshannon and they eventually arrived to me with a charge of three shillings extra, which I refused to pay."

Hundreds of people gave evidence to the Boundary Commission in 1925 and their transcripts are freely available on the UK National Archives website

In Northern Ireland, many nationalist-owned businesses were also suffering as a consequence of punitive fees levied by the Free State.

Newry's oldest bakery firm, Arthur McCann Ltd, told the commission its output had "considerably reduced" since customs charges were introduced on sugary goods.

Its nationalist director, Matthew McCann, said a "protective duty of three pence and three-fifths per pound weight has been imposed on confectionary in the Free State, with the result that my firm cannot possibly compete with the Free State bakeries".

The commissioners also heard concerns from border residents who felt culturally alienated in their new jurisditions.

"I have three children at school, and when they come home I do not understand what they are saying in Irish," said Pettigo merchant Mr Lyttle.

"They are hammering away at Irish today, they are taking their attention away from what they should be learning."

Listening to him was Boundary Commissioner Eoin MacNeill, a revered Irish language scholar and the then Irish minister of education.

What did the Boundary Commission decide?

Eoin MacNeill, from from Glenarm in County Antrim, founded the Irish Volunteers, Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) and countermanded the 1916 Easter Rising

The County Antrim native was the Dublin government's only voice on the commission.

He worked alongside its British-born chairman Richard Feetham and Ulster unionist Joseph Fisher, whom the UK appointed to represent Northern Ireland's interests.

However, MacNeill ended up resigning shortly after the commission's land swap proposals were reported.

According to historian Cormac Moore, Irish negotiators who agreed to a boundary review in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty never envisaged they could lose any territory.

"They firmly believed it was going to see large areas of Northern Ireland go to the Free State - counties Tyrone; Fermanagh; Derry city; Newry," he told BBC News NI.

In reality, the commission recommended transferring about 282 sq m of Northern Ireland land to the Free State, but crucially, they also proposed shifting 78 sq m from south to north.

"Parts of east Donegal and parts of Monaghan were going to go into Northern Ireland from the Free State," Moore explains.

"But also parts of Tyrone, Fermanagh and a big area of south Armagh, including Crossmaglen, were going to go into the Free State from Northern Ireland."

Irish leader William Thomas Cosgrave was blindsided by the Boundary Commission's proposals and quickly moved to cut a fresh deal with the UK

When the Morning Post published the commission's leaked proposals on 7 November, Irish minsters panicked.

Irish leader WT Cosgrave rushed to London in a bid to bury the Boundary Commission's report and stem the political damage.

In exchange for accepting an unchanged border, he negotiated a deal which waived the Free State's obligation to pay about £150m towards Britain's imperial debt.

Moore says it was Irish government's decision to prioritise "financial gain" which "disgusted northern nationalists more than anything".

"Most of them had to accept, whether they liked it or not, that they were going to be in Northern Ireland for a very long time to come and they couldn't rely on the Free State anymore.

"I think that kind of bitterness between northern nationalists and southern governments has remained, you could say, for the last 100 years."

- Published3 May 2021