Damilola Taylor: The fight to protect young lives

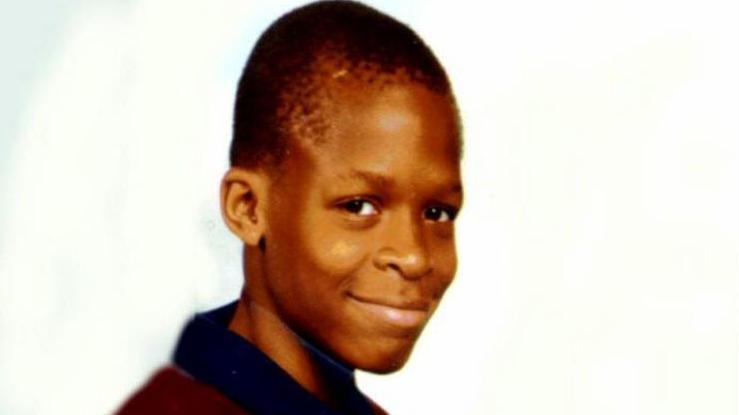

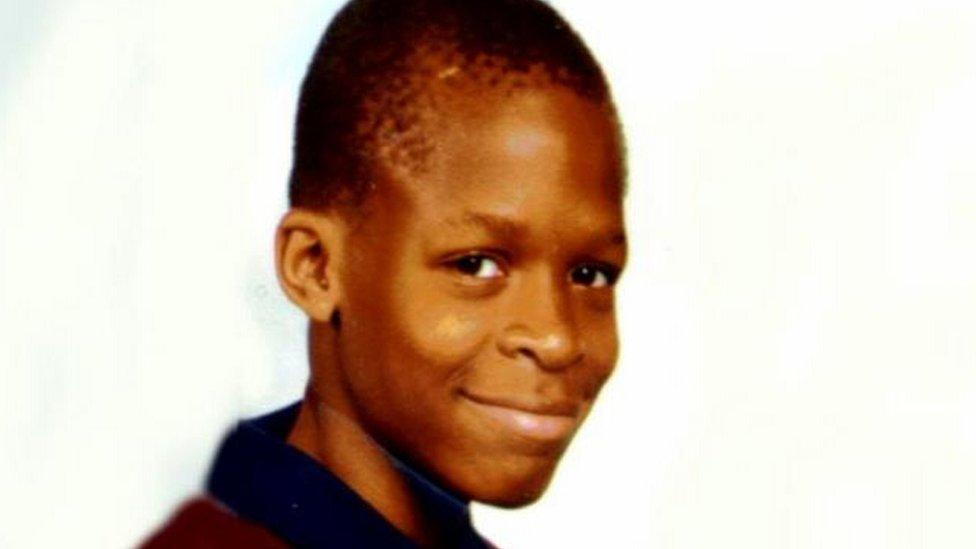

Damilola Taylor had dreamed of becoming a doctor to "save the world"

- Published

A quarter of a century after 10-year-old Damilola Taylor was killed, his family, friends, campaigners and community leaders will gather in central London to honour his memory and confront the continuing impact of youth violence.

Those attending include London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan and Met Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley, who will join the Taylor family to mark a life cut short and reflect on the legacy of Damilola's death.

Twenty-five years ago, on 27 November 2000, Damilola was walking home from Peckham Library after a day at school. Moments later, he was stabbed in the leg with a broken bottle. He staggered to a stairwell on the North Peckham Estate, where he collapsed and died.

His death gripped the country. Damilola's bright smile and his dream of becoming a doctor to "save the world" became symbolic of the lost potential of so many young victims of violence.

Then-prime minister Tony Blair described the killing as "utterly heart-breaking", while TV bulletins led for days with scenes from Peckham.

The killing of Damilola was headline news for days

Millions followed the case as police investigated, and as the Taylor family, who had moved from Nigeria to London seeking better opportunities for their children, faced unimaginable grief.

Damilola's parents, Richard and Gloria, were thrust into the public eye. But instead of withdrawing, they chose to turn their pain into purpose.

The Old Bailey trials that followed were among the most scrutinised of their time. I witnessed them first-hand as a young reporter for BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat, covering the hearings that ultimately saw brothers Ricky and Danny Preddie, aged 12 and 13 respectively at the time of the killing, convicted of Damilola's manslaughter on 9 August 2006 — almost six years after his death.

A legacy built from tragedy

Months after Damilola's death, his father Richard Taylor established the Damilola Taylor Trust. The aim was simple but ambitious: to support disadvantaged young people and provide opportunities that might keep them safe and inspired.

Over the past 25 years, the trust has run mentoring schemes for young people in London's most deprived communities, launched the Damilola Taylor Centre in Southwark, hosted annual awards celebrating youth achievement, partnered with schools, charities and youth organisations and campaigned on youth violence, mental health and safety.

For many in the community, the trust symbolises transformation, resilience and hope.

The Taylor family turned their pain into a purpose

"Everything we do, every young person we reach, is part of Damilola's legacy," said Tunde Taylor, Damilola's brother. "Every anniversary is hard for the family, but this one is poignant because we are also celebrating the work the trust has been doing in his name. His legacy of hope."

Gary Trowsdale, CEO of the trust, said they were dedicated to "creating impactful projects that influence real change".

Many of those who came through the charity's programmes are now adults with families and careers of their own. They credited the charity with giving them a sense of direction and belonging.

Sarah Jones, crime and policing minister, said Damilola's death continued to serve as a "stark reminder of the devastating impact of youth violence".

Knife crime and youth violence

As the country marks the anniversary of Damilola's death, it also confronts the reality of youth violence today.

In the year ending March 2025, police recorded about 53,000 offences involving knives or sharp instruments in England and Wales, according to ONS data, external.

This was 1.2% lower than in 2023-24 and 3.8% lower than in 2019-20.

The Metropolitan Police said in the 12 months to August 2025 there were 1,154 fewer knife crime offences in London than the previous 12 months — a drop of 7%.

Young people remain disproportionately represented as both victims and perpetrators. London consistently records the highest knife-enabled offending rates in the country.

While some short-term trends show slight improvements, including a small decline in knife crime over the past year, the long-term picture remains troubling.

The Met Police recorded 1,154 fewer knife crime offences than the previous 12 months

Youth workers say cuts to early-intervention services, the closure of youth centres and an increase in school exclusions have all contributed to the rise in violence among young people.

Police point to county lines gangs exploiting teenagers. Mental health specialists highlight the impact of trauma, poverty and social media disputes on platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat.

They also say no single factor explains it. But all agree it is complex, entrenched, and still costing young lives.

Analysts, police officers, teachers and youth workers have identified a series of interconnected pressures.

Deprivation and inequality: Many of the areas hardest hit by knife violence also face the highest levels of poverty, unemployment, and overcrowded housing

Cuts to youth services: Hundreds of youth clubs have closed since 2010. The loss of these safe spaces has left young people with fewer alternatives to the streets

School exclusions: Research shows children excluded from school are more vulnerable to grooming by gangs and criminal networks

Social media escalation: Arguments that once ended in the playground now escalate online, spreading rapidly and sometimes ending in street violence

County lines exploitation: Teenagers are groomed to transport drugs across the UK — often under threat

Trauma and mental health: Childhood violence, instability, poverty and stress can lead to impulsive behaviour, anger, and vulnerability

Community leaders say tackling knife crime requires more than policing — it demands investment, compassion, and prevention.

As part of the 25th anniversary on Thursday, community leaders, educators and parents will call for a renewed national strategy to prevent youth violence.

Many have echoed the same message: invest in early intervention, rebuild youth services, improve mental health access, strengthen collaboration between schools, police and families and give young people opportunities to thrive.

Twenty-five years on, Damilola is remembered not only for the tragic way his life ended, but for the hope and determination he continues to inspire.

His father, Richard Taylor, once said he wanted his son's name "to be a symbol of greatness, not sorrow."

Looking at some of the young people supported by The Damilola Taylor Trust over more than two decades — determined, ambitious and hopeful — it is clear that this wish is being fulfilled.

Damilola's legacy lives on, and the fight to protect young people continues.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published29 March 2024

- Published27 November 2020

- Published27 November 2010

- Published8 September 2010