'We fought pit closures till the end'

An MP said people would not want to work in the mines nowadays

- Published

Exactly 40 years ago today, coal miners in Kent marched back to work.

They were among the last to hold out during an industrial dispute between the National Union of Mineworkers and Margaret Thatcher's government.

The 1984-1985 strike - one of the biggest and bitterest in UK history - ended in defeat for the miners.

Kent's mines - Tilmanstone, Snowdown and Betteshanger - were closed in 1986, 1987 and 1989 respectively, but the consequences of what happened are still debated.

So what is the legacy of the strikes?

'Stronger together'

Billy Powell, from Ramsgate, was in his late 20s and working as a "face worker" when the strike was called to resist colliery closures across the country, announced by the National Coal Board.

"We knew it would be our turn next," he said.

Though Mr Powell said they would have gladly returned to their mining jobs that were better paid than others in the area, he said the walkout lasted far longer than the miners expected, leaving them without pay for a year.

"It was a long time," the 64-year-old said.

Mr Powell said he never thought of breaking the strike

Still, he said there was "no chance" of him breaking the strike.

"It just didn't seem like the right thing to do," Mr Powell told the BBC.

"When you worked at the pit, you soon learned that you're stronger together than you are as an individual.

"I have never had another job like that again."

'Dangerous and dirty work'

Even if the strikers won, Lord Mackinlay of Richborough, Craig Mackinlay, the former Conservative MP for South Thanet, said he doubted whether people today would want to work down the mines, or if they would still be open due to net zero climate targets.

"We have no concept of what a tough life that was," he said.

"I take my hat off to the miners. It was dangerous and dirty work.

"But there are times when you just have to move on."

Lord Mackinlay added the coal being extracted in Kent was comparatively more expensive than that produced in other countries, though some dispute this claim, arguing that other factors were at play.

"It wasn't nasty. It was pure economics. If the economics stacked up, we would still have coal," he said.

Being a miner in Kent could be a dangerous occupation

Lidia Letkiewicz-Rush, curator at the Kent Mining Museum, told the BBC that some miners' families had bad memories of the strikes due to financial hardship and the absence of a father out picketing.

The children of strikers would argue at school or be treated differently, she added.

"It probably builds a lot of confusion and resentment for the difficulty [of the situation], especially if they were younger children who just couldn't understand exactly what was happening," she said.

While "devastating" for some, Colin Varrall - whose father and grandfather worked at Tilmanstone - told the BBC: "Some people considered themselves better off when the strikes ended and the Kent pits closed."

Some were employed on the Channel Tunnel, he said.

But Mr Varrall added many miners were blacklisted due to their strike activities.

Others did not have skills or qualifications and struggled to pick up work, he said.

The strikes took a toll on some mining familes, one expert said

Jim Davies, who described himself as one of the last miners, worked down the mine since leaving school and was an overman before the strike began.

Though the community was slowly fading as people passed away, he said the strikes brought people together, detailing that other local unions supported the miners, who themselves set up community organisations that last today.

Mr Davies, who lives in Deal, said the miners - often facing prejudice from the wider public during the time - felt proud about the strike, despite its failure.

"It's better to fight and lose than not fight at all," the now 83-year-old said.

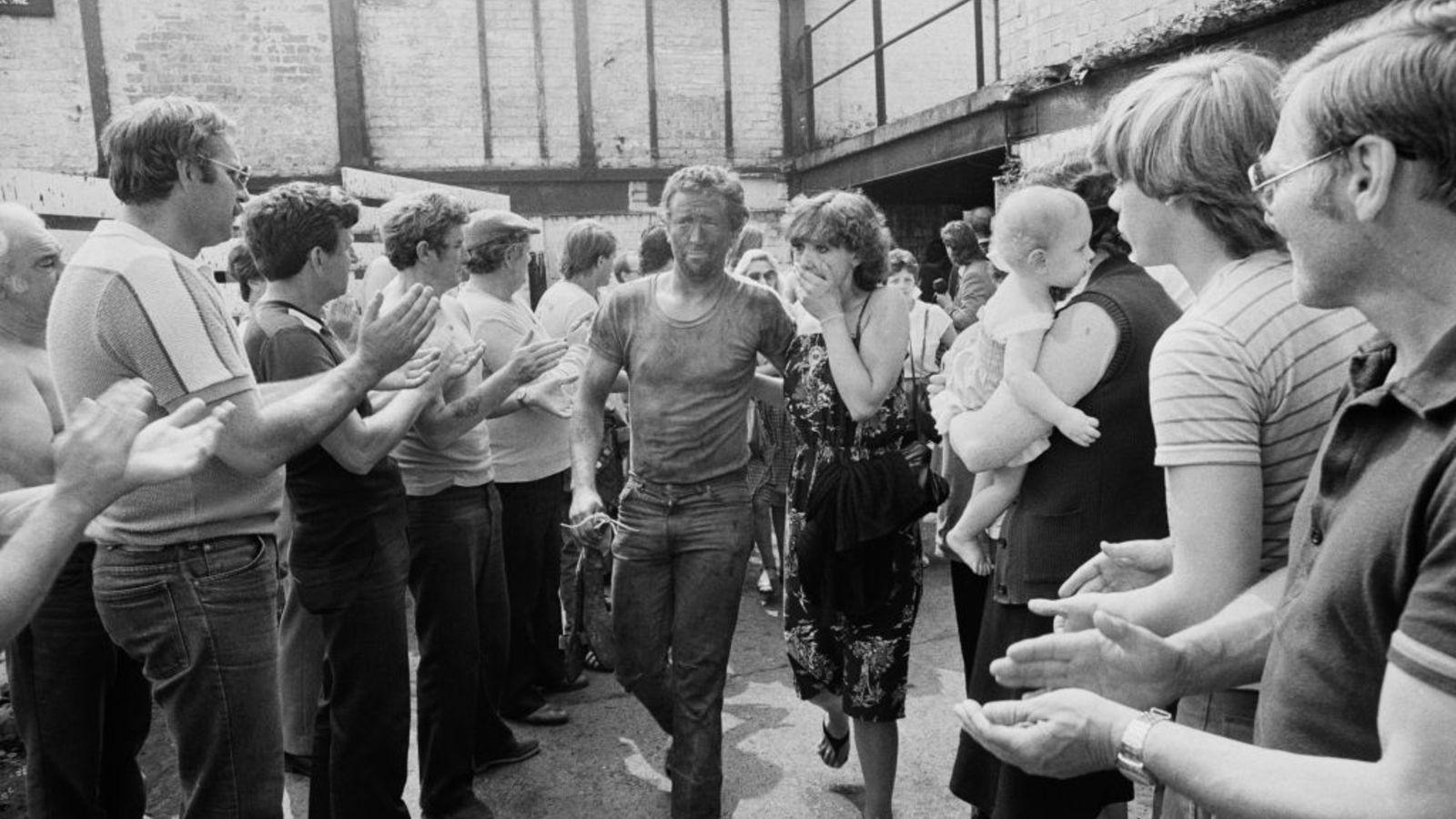

Support for the miners came from across the UK and beyond

Ms Letkiewicz-Rush from the Mining Museum added that the legacy of the strikes and mining in Kent will always be important.

"You need to know where you've come from. We need to know why society is the way it is. We are the way we are because of those before us in every way, shape, and form.

"If it wasn't for coal mining in this area at this specific time, Kent wouldn't be what it is now."

Follow BBC Kent on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to southeasttoday@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 08081 002250.

See also

- Published18 August 2014

- Published14 November 2012

- Published30 October 2014