The coal mine that felt like a second home

Littleton Colliery heading team stand by the cutting machine

- Published

Littleton Colliery closed for the final time 30 years ago with the loss of more than 500 jobs. It was the last pit to shut in Cannock Chase, bringing an end to hundreds of years of mining heritage in the area. The BBC spoke to some of the people who worked there.

There are very few signs Littleton Colliery ever existed in the small village of Huntington, on the outskirts of Cannock.

It has been replaced by a housing estate, school, park and pharmacy.

The coal mine may have all but disappeared but it is still etched in Peter Timlin's mind.

"When I come down the A34, the pit's there still in front of me", he said.

The former electrician worked there for 33 years, called out to repair machines and involved in the mechanisation of the colliery.

He said: “You either hated it or it became a second home, it was like being in another dimension.”

Littleton Colliery closed on 10 December 1993 with the loss of more than 500 jobs

The 83-year-old started working nights there when he was 21 and covered an area of up to eight miles (13km).

"I had the free run of the pit and I really, thoroughly enjoyed it. I walked absolutely miles," he said.

He was doing triathlons at the time so found it to be good training.

But Mr Timlin admitted some of the conditions down the mine were "absolutely atrocious".

Peter Timlin at the entrance to the underground locomotive garage

He added: "Quite a lot of people would think you must be insane. It's hard to believe that I actually liked it."

His mother was among those who could not understand why he wanted to work there and "cried her eyes out" when she found out.

Peter explained his uncle Bill, his mother's brother, had died there "in a well-known accident in 1938, where they got gassed".

But he said he never felt afraid.

"If you were frightened of the pit it was no place for you," he added.

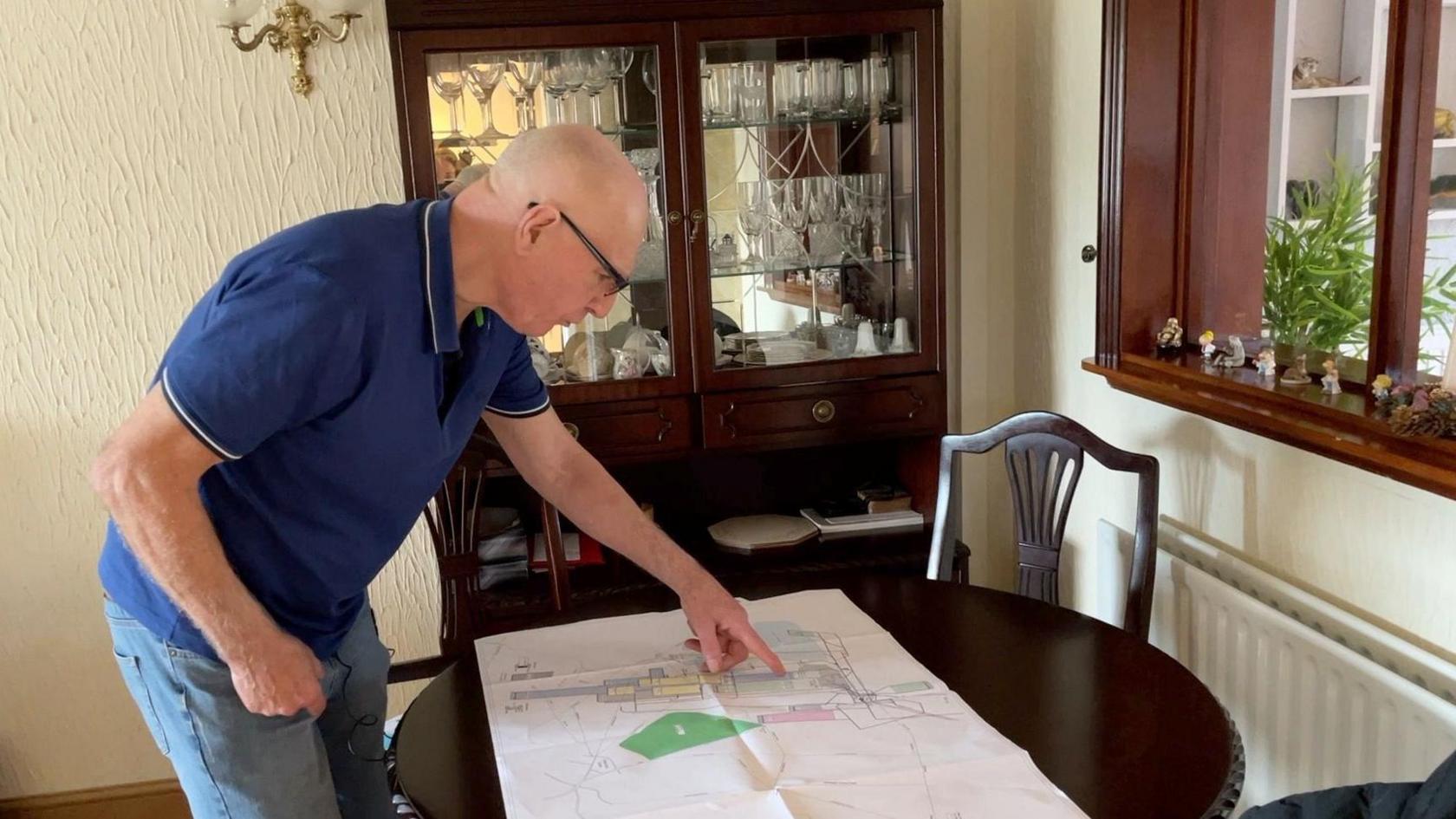

Always interested in the workings of the coal mine, Peter created a map of the south side and eventually plans to draw up the north side.

Mr Timlin has designed a map of the colliery

Littleton Colliery was one of 48 pits on the Cannock Chase coalfields, an area defined by the coal industry.

It became one of the biggest pits in the Midlands, covering an area below ground of about 13 sq miles (34 sq km).

At its height, it employed 1,900 miners.

It was the last remaining colliery to close in Cannock Chase on 10 December 1993.

Former miner Ron Kenyon believed the pits were closed down "too soon, and too fast".

The 80-year-old great-grandfather said they were not thinking about the future security of the country.

"Look at the mess we’re in now”, he said, referring to the recent energy crisis.

He also believed the closures were politically motivated "because the government didn't like the industry".

At the time, British Coal described it as an economic necessity as it competed with cheap imports of coal.

Ex-miners Ray Griffiths and Ron Kenyon still go for drinks every Friday

Mr Kenyon was born 300 yards (274m) from the gates of Littleton Colliery and worked there for 29 years.

He walked out for the whole year of the miners strike of 1984-5, industrial action which divided families and communities.

"There was a lot of bitterness and hard times, but it's gone," said Mr Kenyon, who was a branch committee member of the National Union of Mineworkers.

A few years after the strike he took redundancy.

But he made long-lasting friendships and still meets former colleagues every Friday and Sunday night at the local social club.

Among them was former miner, Ray Griffiths, 81, who worked at the colliery for 30 years.

They served on Huntingdon Parish Council together and helped shape the regeneration of the village after the pit closed.

On 17 June 1971, Mr Griffiths had a nasty accident and was "buried in the pit".

He had to be pulled out and it affected him in later life, with back problems and surgery for hip replacements.

Both men still agreed if they had their time again, they would go back down the pit.

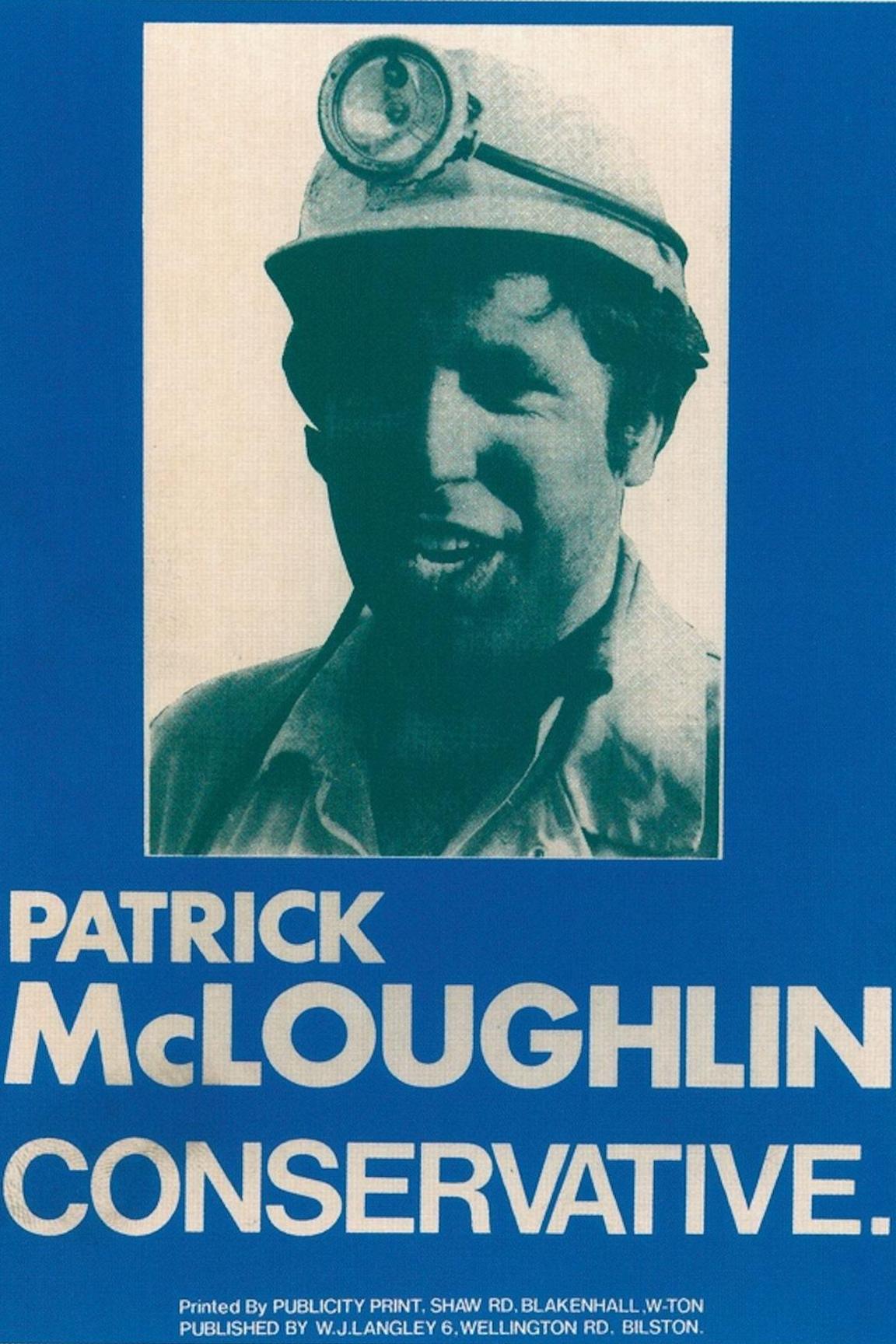

Publicity print for Patrick McLoughlin's political campaign

The lives of other miners took a different turn.

In 2012, Prime Minister David Cameron told the House of Commons: "I've taken a miner, put him in the cabinet and he's running the railways."

Lord Patrick McLoughlin, 66, the son and grandson of coal miners, worked at Littleton Colliery as a miner from 1979.

Around the same time he was elected as a councillor in Cannock Chase and served on Staffordshire County Council.

"There was good banter, I was a known Conservative, there was a lot of leg-pulling. It prepared me well for a life of politics in due course," he said.

But things soured as a result of the industrial action of 1984-5. He was among a small number who initially crossed the picket line, although that number would grow as the strike action continued.

"I didn’t go on strike because we had a ballot at Littleton and the vote was to continue working," he explained.

Work was pretty difficult after that.

"Those who’d been out on strike weren’t very forgiving of those who broke the picket line," he said.

Lord Patrick McLoughlin served as Transport Secretary in David Cameron's government

Not long after the strike, his career as a miner came to an end when he was elected MP for West Derbyshire in 1986.

He went on to become a cabinet minister.

Lord McLoughlin said: "I left school at 16, and I ended up sitting round the cabinet table and I was able to say things to people who’d been to university and sort of occasionally say to them: ‘Have you really thought this through?’."

"I’m very proud of my background."

Reflecting on the closure of Littleton Colliery, he said it was sad but added that it was "a dangerous environment", with men going a thousand feet (305m) below ground to get out coal.

"While I worked there, there were some fatal accidents that had a terrible effect on everyone who worked there," he said.

He was created a life peer in 2020.

This memorial garden, featuring one of the winding wheels, was one of the few signs of Huntingdon's mining past

Without a coal mine, Huntington is now mainly a commuter base for neighbouring towns.

The old site has been completely transformed, with just a few signs of Huntington's mining heritage, including a memorial garden and monuments marking where the shafts once lay.

The Museum of Cannock Chase is putting on a 'Littleton exhibition' to mark 30 years since the pit closed.

It will be on show from 9 January to 24 February 2024.

Related topics

- Published3 December 2023

- Published30 November 2023

- Published25 October 2023