Extreme drought areas treble in size since 80s - study

Nyakuma and her husband Sunday struggle to find food in South Sudan, which has been hit by drought and floods

- Published

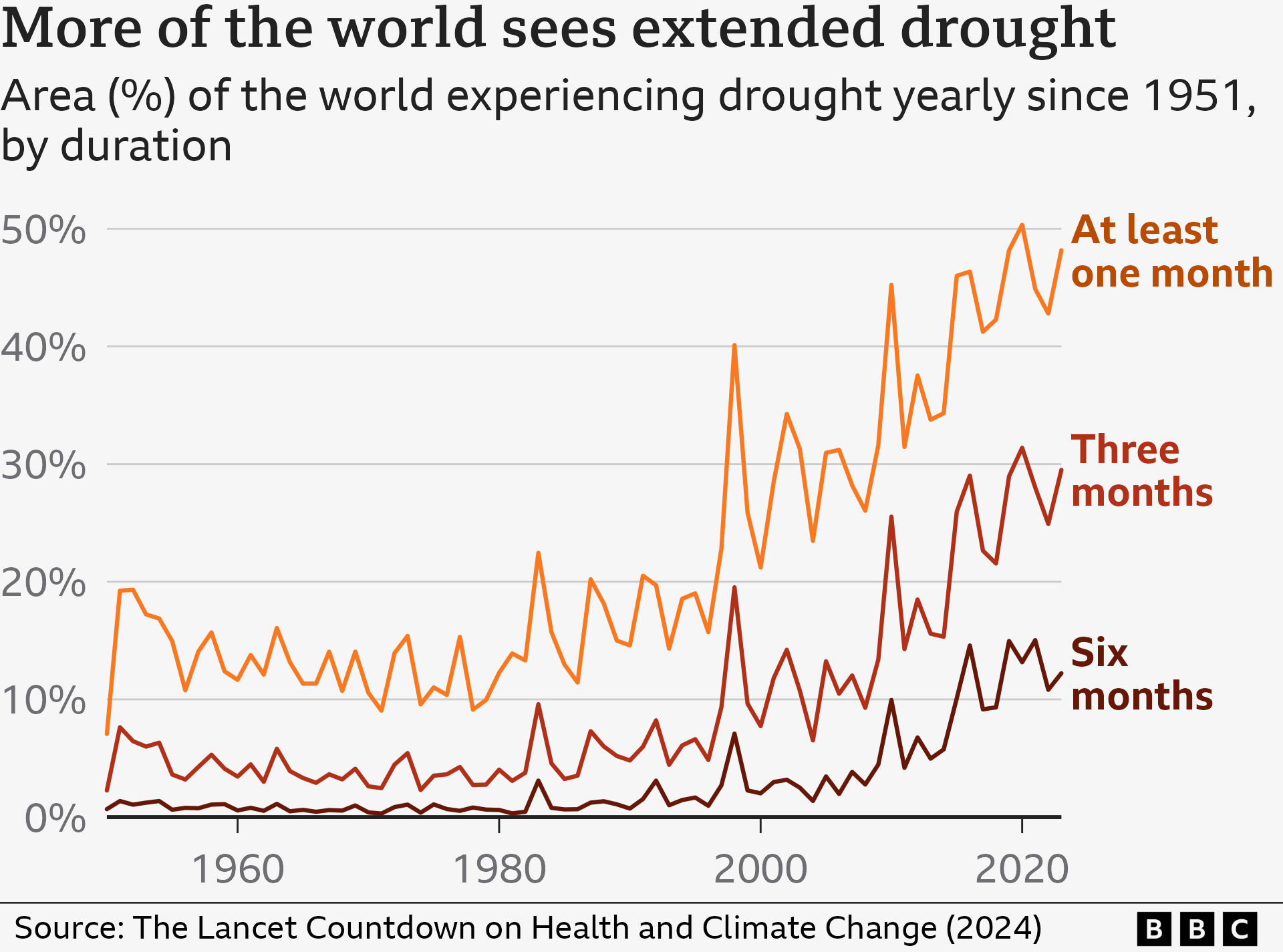

The area of land surface affected by extreme drought has trebled since the 1980s, a new report into the effects of climate change has revealed.

Forty-eight per cent of the Earth’s land surface had at least one month of extreme drought last year, according to analysis by the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change - up from an average of 15% during the 1980s.

Almost a third of the world - 30% - experienced extreme drought for three months or longer in 2023. In the 1980s, the average was 5%.

The new study offers some of the most up-to-date global data on drought, marking just how fast it is accelerating.

The threshold for extreme drought is reached after six months of very low rainfall or very high levels of evaporation from plants and soil - or both.

It poses an immediate risk to water and sanitation, food security and public health, and can affect energy supplies, transportation networks and the economy.

The causes of individual droughts are complicated, because there are lots of different factors that affect the availability of water, from natural weather events to the way humans use land.

But climate change is shifting global rainfall patterns, making some regions more prone to drought.

The increase in drought has been particularly severe in South America, the Middle East and the Horn of Africa.

In South America's Amazon, drought is threatening to change weather patterns.

It kills trees that have a role to play in stimulating rainclouds to form, which disrupts delicately balanced rainfall cycles - creating a feedback loop leading to further drought.

Yet, at the same time as large sections of the land mass have been drying out, extreme rainfall has also increased.

In the past 10 years, 61% of the world saw an increase in extreme rainfall, when compared with a baseline average from 1961-1990.

The link between droughts, floods and global warming is complex. Hot weather increases the evaporation of water from soil which makes periods when there is no rain even drier.

But climate change is also changing rainfall patterns. As the oceans warm, more water evaporates into the air. The air is warming too, which means it can hold more moisture. When that moisture moves over land or converges into a storm, it leads to more intense rain.

The Lancet Countdown report found the health impacts of climate change were reaching record-breaking levels.

Drought exposed 151 million more people to food insecurity last year, compared with the 1990s, which has contributed to malnutrition. Heat-related deaths for over 65s also increased by 167% compared to the 1990s.

Meanwhile, rising temperatures and more rain are causing an increase in mosquito-related viruses. Cases of dengue fever are at an all-time high and dengue, malaria and West Nile virus have spread to places they were never found before.

An increase in dust storms has left millions more people exposed to dangerous air pollution.

“The climate is changing fast," says Marina Romanello, executive director of the Lancet Countdown.

"It is changing to conditions that we are not used to and that we did not design our systems to work around."

For the series Life at 50 degrees, BBC World Service visited some of the hottest parts of the world, where demand for water was already high. We found that extreme drought and rainfall had further squeezed access to water.

Since 2020, an extreme and exceptional agricultural drought has gripped northeast Syria and parts of Iraq.

What remains of a tributary of the Khabor river in Hasakah, Syria

In the past few years, Hasakah, a city of one million people, has run out of clean water.

“Twenty years ago, water used to flow into the Khabor River but this river has been dried for many years because there is no rain,” says Osman Gaddo, the Head of Water Testing, Hasakah City Water Board. “People have no access to fresh water.”

When they can’t get water, people make their own wells by digging into the ground but the groundwater can be polluted, making people ill.

The drinking water in Hasakah comes from a system of wells 25 kilometres away, but these are also drying and the fuel needed to extract water is in short supply.

Clothes go unwashed and families can’t bathe their children properly, meaning skin diseases and diarrhoea are widespread.

“People are ready to kill their neighbour for water,” one resident tells the BBC. “People are going thirsty every day.”

In South Sudan, 77% of the country had at least one month of drought last year and half the country was in extreme drought for at least six months. At the same time, more than 700,000 people have been affected by flooding.

“Things are deteriorating,” says village elder, Nyakuma. “When we go in the water, we get sick. And the food we eat isn’t nutritious enough”.

Nyakuma has caught malaria twice in a matter of months.

Her family lost their entire cattle herd after flooding last year and now survive on government aid along with anything they can forage.

“Eating this is like eating mud,” says Sunday, Nyakuma’s husband, as he searches floodwater for the roots of waterlillies.

During a drought, rivers and lakes dry up and the soil gets scorched, meaning it hardens and loses plant cover. If heavy rain follows, water cannot soak into the ground and instead runs off, causing flash flooding.

“Plants can adapt to extreme drought, to an extent anyway, but flooding really disrupts their physiology," adds Romanello. "It is really bad for food security and the agricultural sector."

Unless we can reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and stop the global temperature from rising further, we can expect more drought and more intense rain. 2023 was the hottest year on record.

“At the moment, we are still in a position to just about adapt to the changes in the climate. But it is going to get to a point where we will reach the limit of our capacity. Then we will see a lot of unavoidable impacts,” says Romanello.

"The higher we allow the global temperature to go, the worse things are going to be”.

Zimbabwe declares national disaster over drought

- Published3 April 2024

Deadly Africa heat caused by human-induced warming

- Published18 April 2024

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to get exclusive insight on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC's Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.