The pains of plugging budget holes with renewables windfall

- Published

First Minister John Swinney says he hopes to avoid the £460m raid on a long-term investment fund announced by Finance Secretary Shona Robison to balance the books this year.

He said so as he officially opened the onshore maintenance base in Buckie for one of Scotland's biggest offshore windfarms - Moray West. He wishes to be seen as a champion of the renewable energy industry.

And on a sunny day on the Moray coast, that was how it looked.

But that £460m was to support the transition to greener energy. Yet Shona Robison says she intends to use that money, if the UK government does not fund public sector pay deals, which have been coming in well ahead of the 3% increase she budgeted this year.

Scottish government confirms £500m in cuts

- Published3 September 2024

Scotland's fiscal outlook messy and 'painful'

- Published27 August 2024

Grim spending forecast suggests stormy times ahead

- Published27 August 2024

The budget problem and the raid on a long-term fund for short-term cash are being blamed on the UK government. Mr Swinney accuses it of a return to 'austerity', meaning a squeeze on public spending.

But these are also embarrassing circumstances for the Scottish government.

Even before the programme of cuts to public spending could be announced, the official fiscal watchdog had nailed the problem with budget planning on the door at St Andrew's House: under-estimating the cost of public sector pay, freezing council tax, and expanding relatively generous welfare payments for Scots.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission pointed out that choices were being made at Holyrood before Labour came to power in Downing Street. Those choices, in the budget set out in draft last December, set the course for the mid-year budget crunch we're now seeing.

The scale of Ms Robison's recruitment freeze and spending claw-back remains unclear, at least until Chancellor Rachel Reeves reveals her plans at the UK Treasury. But if the £460m is required, the Scottish government is undermining its own arguments for long-term investment in energy and a 'just transition' from fossil fuels to renewable power.

That plan has been awaited for a long time. It requires some difficult wording on the future path for Scotland's oil and gas industry, which has been on its own transition from the backbone of the economic case for Scottish independence (see the referendum campaign 10 years ago) to something of a political pariah.

But publication now looks imminent. It will have to address the limited economic benefit accruing to Scotland from renewable power. The Moray West wind farm has no more than 70 permanent jobs attached. The manufacturing has been done in the east of England and beyond.

The strategy will require funds to help pay for transition, and that looks a shaky prospect if money earmarked for it is being diverted to avert strikes by bin collectors, teachers and doctors, to freeze council tax and fund welfare payments.

So as it is a vital part of plugging the hole in the Holyrood budget, it's worth a closer look at the ScotWind windfall.

Big prospects

The story began in English waters. Offshore wind looked very expensive, and to create incentives for private sector firms to invest in it, the UK government offered 'Contracts for Difference'. These are promises to fund developers with a minimum price for power per megawatt hour, while also clawing back revenue above that level.

Who will pay? Not the government, but those who pay household and business electricity bills.

A series of auctions, in which the winners offer to supply power into the grid at the lowest price, saw the cost of offshore wind plummet at each time of asking. It was a highly effective way of driving the industry to become more cost-efficient. The more turbines they installed, the more efficient they became.

As a consequence, there are more than 2,000 wind turbines installed in UK waters. It was the country with the biggest such investment until China recently overtook it.

Thousands of wind turbines have sprung up around the UK waters

That auction process worked well until last year, when an auction round was pitched by the government at too low or ambitious a price, and there were no bidders. Last week, a more successful bidding round secured 131 winning bids.

Some 37 projects securing Contracts for Difference were in Scottish waters, including fixed and floating offshore windfarms, as well as onshore wind, tidal and solar arrays.

Scotland, meanwhile, had gone big with onshore wind power, where Contracts for Difference drove down prices so much that some new developments can stand alone on a commercial basis. England effectively blocked new plans for onshore turbines, where they met with local opponents.

Going offshore from Scottish waters offered the prospect of consistent wind at higher speeds, but in deeper water with higher development costs. So Scotland came to offshore wind more recently. It has only a small share of installed capacity, but big prospects.

Bottlenecks

Another auction process, for the right to develop a sea area, produced another astonishing result in English waters. Private sector developers were willing to bid far more than expected.

An auction for areas of Scottish seabed, known as ScotWind, was halted while the agency which owns and leases the seabed, Crown Estate Scotland, recalibrated what it could expect - concluding it could be as much as ten times more than anticipated.

In April 2022, Crown Estate Scotland announced the winning bidders for 17 sea areas around Scotland's coast, including some large ones around Orkney, as well as areas off Lewis and Islay. Later that year, three more sea areas were added off Shetland. Total takings from the auction: £755m.

And that's only for the right to plan and develop these sites. It does not secure planning rights, or consent to plug a windfarm into the national grid, or one of those Contracts for Difference.

The Moray East offshore wind project was granted planning consent in 2014 by the Scottish government

Each winning bid still carries significant technical risks for developing offshore in wild waters. Of the 20 areas, 13 are to use floating wind turbines, which are much less mature in their design.

There is financial risk. These auction bids were ahead of interest rates going up, inflation applying to supplies and bottlenecks in the development process.

There is, for instance, a shortage of the huge barges required to install turbines which now reach more than 200 metres (656ft) above sea level. They have to be booked well in advance, and competition for them has pushed up prices.

The ScotWind windfall could have been more if conditions had not been applied. Crown Estate Scotland chose bids that looked most credible as well as being lucrative, with a large share of the supply chain close to home, and a clear route to being installed within 10 years, which is when the development rights run out.

Crown Estate Scotland has an interest in seeing these plans progress, because it will eventually be charging windfarm owners an annual rent for the seabed once the power and the cash begin to flow.

It has the same financial interest as the Scottish government. Although its name is derived from the estates owned historically by kings and queens, it is wholly owned by Scottish ministers, and all its profits flow into their coffers.

So that is where the windfall reaches Shona Robison. This is a one-off payment, to be followed, in 10 years or so, by more modest annual leasing profits.

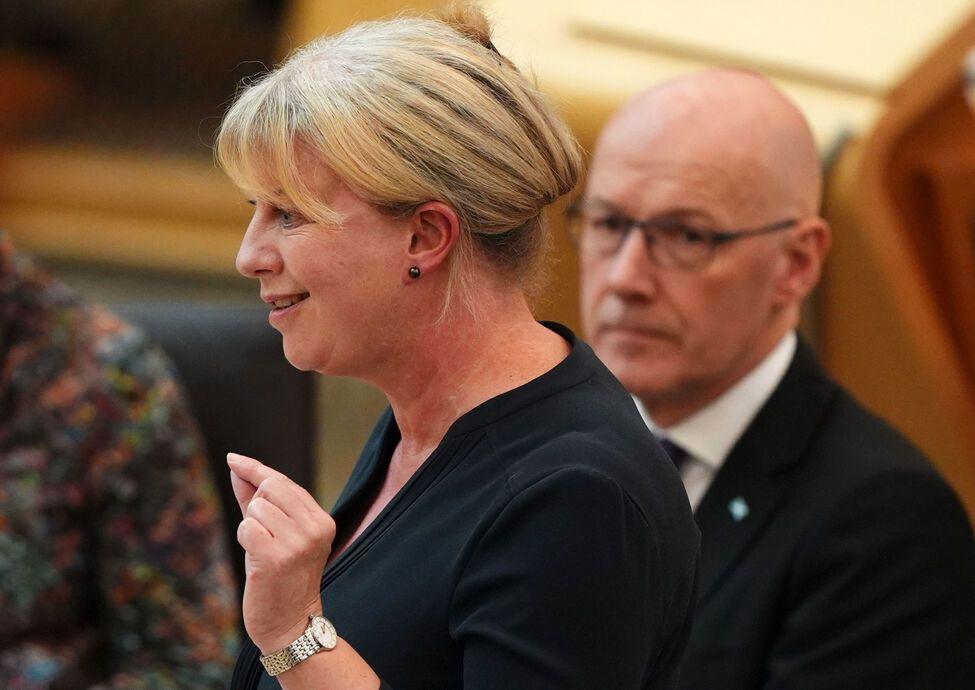

Shona Robison warned that large cuts to public services are on the way

Putting that money into long-term investment in the energy transition is in line with the SNP's long-standing criticism of the UK government for failing to put aside oil and gas revenues. For 50 years, these have been absorbed into the giant bank account at HM Treasury, some of them to pay for capital projects and a lot of them to avoid higher taxes.

By contrast, Norway at first used its North Sea windfall to pay off its government debt, and for the past 33 years, while levying very high personal taxes, it has taken the long-term view and built up a colossal investment fund, by last month worth £1.3 trillion.

Supporters of independence have long argued that Scotland could have done the same. And maybe it could. But to save and invest funds for the long term, a government has to avoid the temptation of plugging gaps in budgets, to protect priorities in the short term.

That is exactly what the Scottish government is now doing. And while public sector pay will have to be funded next year, with pressure from public sector unions for a further rise at least to match higher prices, there will be no ScotWind windfall available.

'Frittered away'

Nor will public sector unions take kindly to being accused of forcing ministers to raid the Scottish government's investment fund.

A letter from the GMB Scottish secretary Louise Gilmour states: "The decision to use £460m of one-off ScotWind income to plug the gap in Scotland’s finances is unsustainable and represents poor financial planning. For our members in energy, it yet again obliterates the claim of a ‘just transition’.

"These funds should have been used to build the renewable supply chains across Scotland. Instead, they have been squandered."

The union leader isn't holding back: "Just as Thatcher raided Scotland’s oil and gas profits preventing the creation of a sovereign wealth fund akin to that of Norway, Scotland’s future in renewables is now being frittered away.

"Failing to invest and plan in the future of our energy network undermines the Scottish government’s own ability to fund future spending in the public sector."

So, not much thanks there to Shona Robison for funding those union pay demands. Plugging that budget hole looks set to become more politically painful before it's over.

- Published26 March 2024

- Published3 September 2024

- Published18 August 2024