Abba filmmaker angered by striking miners portrayal

Kjell-Åke Andersson returned to the former mining village of Oakdale almost 40 years after making his documentary there

- Published

What do one of the best-selling groups of all time - Abba - and Welsh miners have in common?

Both have been captured on film by Swedish director Kjell-Åke Andersson.

Three years after directing one of Abba’s final music videos, The Day Before You Came, he travelled to south Wales to make a documentary about the miners' strike.

The film, Breaking Point, is a snapshot of life in Oakdale, Caerphilly county, in the winter of 1985 - a month before the strike ended.

Kath and Ray Francis say they got caught up in the politics of the strike and it inspired her to go to university

"For me it was about showing the miners’ solidarity instead of Thatcher’s propaganda," said Andersson.

The 75-year-old filmmaker returned to the south Wales valleys to meet some of the families he’d not seen for almost 40 years.

Ray and Kath Francis, who live in the same house in Ystrad Mynach where their four children grew up, are one of the focal points of the documentary.

Between 1984-85, Ray was among 22,000 other Welsh miners who were on strike.

His wife, Kath, joined the many other women who supported the miners by setting up food collection and distribution groups.

“When I met Kath and Ray again, it was very emotional for me - and in the same house 40 years on – it was so emotional," said Andersson.

The documentary shows Oakdale miners on the picket line in the village discussing the latest developments during the strike

The national miners' strike of the 1980s caught the attention of the world's media.

But Andersson didn't feel the situation of the miners was being portrayed fairly by international media back home in Sweden.

He had already experienced the effect of the miners' strike on families in Bargoed during 1974, where he'd spent many months as a photographer.

"In 1984, I was angry because the newspapers and the TV was describing the strike from Mrs Thatcher’s point of view and I hated that, so I said I need to go there and make a documentary because this is not the right view of the strike," he said.

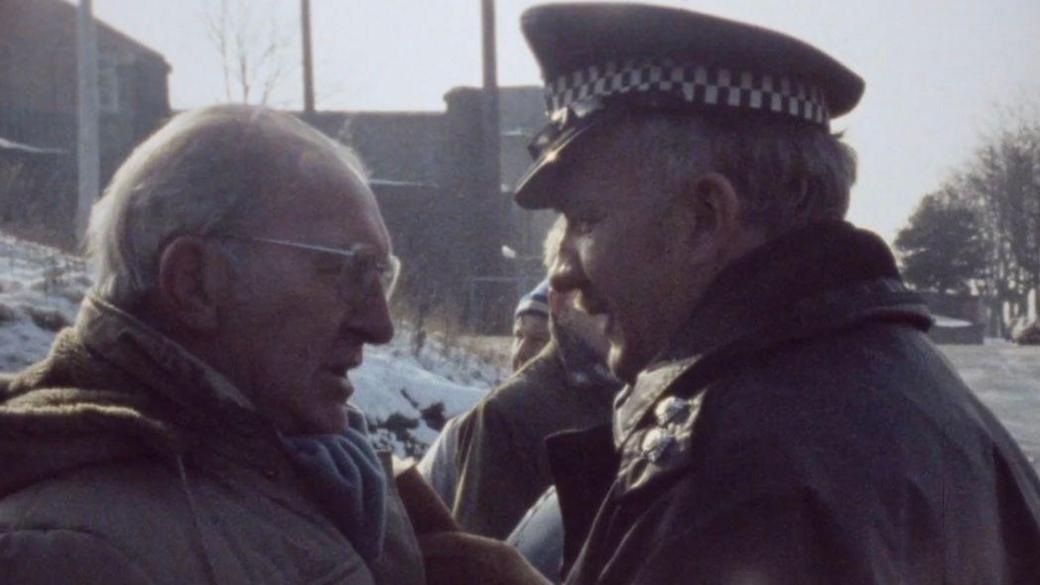

A NUM lodge secretary clashes with a police officer on the picket line outside Oakdale colliery in Breaking Point

Andersson said he wanted to show the solidarity of miners in the south Wales valleys and how the support of the women was a crucial part of their year-long strike.

The experience of the strike transformed many women's lives, including Kath Francis, who went to study for a degree at university and became a social worker.

Her husband Ray said the experience of joining miners on picket lines and organising food collections for the miners made her more confident.

"It was wonderful. We got really caught up in the strike," he said.

Miners' strike rage fuelled Manics success - Wire

- Published31 August 2024

How did the miners' strike affect Wales?

- Published18 February 2024

No 10 behind Orgreave violence - government lawyer

- Published12 July 2024

"I would take the children to school. I would learn how to cook. We would share out the chores.

"I will say this much and a lot of people will say the same, if it wasn’t for the women, we wouldn’t have lasted that long."

Andersson said he quickly came to realise how women's roles were changing.

"I think the strike had a good effect on the women who got a chance to act, not just as a woman or a wife, but in some ways, they were at the same level as the men. Their position was in the front and not in the background," he said.

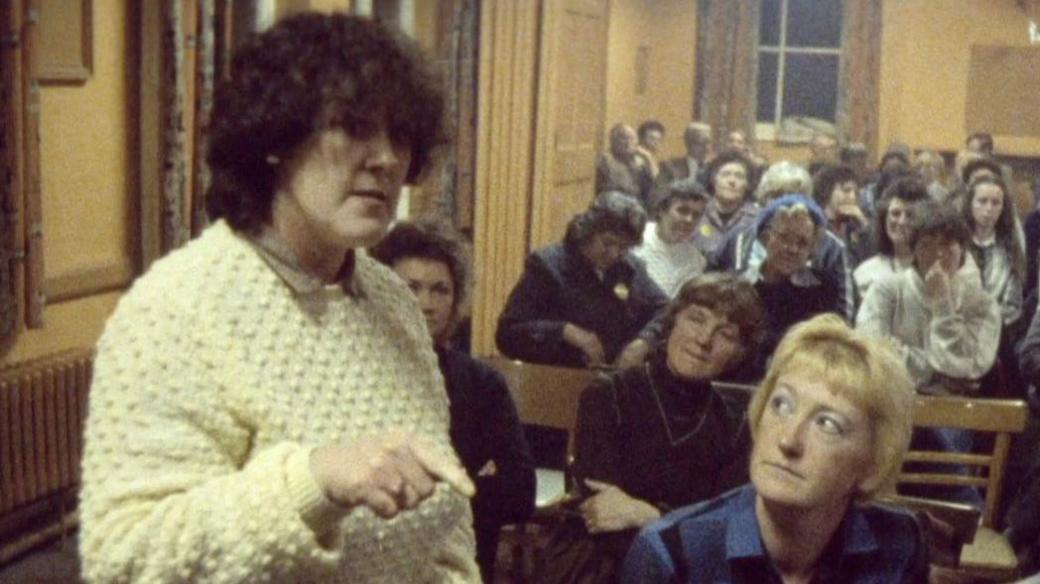

Margaret Matthews in Breaking Point, making a point during a heated exchange at the local food committee meeting

Kath and a few other women are seen knocking on doors in their local area asking for donations of money or food for the miners.

There’s also a heated exchange in a meeting between the miners’ wives and the secretary of the food committee.

Margaret Matthews tells him: "One [miner] told me, I’m not going out in this, it’s raining. We go out in it and it’s their bloody fight..."

Four decades later and her recollection of the incident is vague, but Margaret said she still remembers feeling angry about the situation.

"The lodge secretary rang my husband and asked him if he’d shut me up – to come and have a word [with] me because he said I was upsetting the men.

"I was quiet. I still am, but that just got me. We were fighting for our lives," she said.

Oakdale Miners' Institute, which is now located at St Fagans National Museum of History, features throughout the film as miners gathered to discuss the strike

Poverty and despair had increased during the course of the strike, which led to many miners across Britain returning to the pits.

On 3 March 1985, miners returned to work on the instruction of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Breaking Point highlighted the solidarity of many mining communities in south Wales during what was to become the final few weeks of the strike.

Andersson said he did not sense the strike would end soon while he was filming the documentary.

"I didn’t feel a breaking point," he said.

Shortly after he returned to Sweden to edit the film he learned that it had ended.

"I had a short time to make the film and we just concentrated on one family and some other people and the union meetings," he added.

"Maybe if I had done more interviews with other people maybe I’d have seen that, but this was my experience of it."