BBC hears of horror and hunger in rare visit to Darfur massacre town

- Published

No-one lives in the ghostly outskirts of el-Geneina any more.

But its empty buildings still stand to tell their shocking stories, loudly and clearly.

Charred homes and shops are peppered with bullet holes. Doors are wrecked. Metal shutters are smashed. Rusting Sudanese army tanks dot the streets.

In this rare trip for international journalists into Darfur, we could still smell the fires which blazed here last year.

“It was utterly chilling to drive through these smoked-out ruins and ghost towns,” reflected the UN’s new relief chief Tom Fletcher, whose visit to this hardscrabble capital of West Darfur marked the first time a senior UN official was able to visit this territory since Sudan’s vicious war erupted 19 months ago.

“Darfur has seen the worst of the worst,” is how Mr Fletcher, the Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, described its calamity.

“It’s facing this crisis of protection, including an epidemic of sexual violence, as well as the spectre of famine.”

His short but significant visit only became possible after extensive negotiations with Sudan’s two main rival forces – those headed by Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), who heads the government recognised by the UN, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) of Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, who are now in charge in most of Darfur.

UN officials refer to the RSF as “those in control of the area”.

It was RSF fighters, along with allied Arab militias, who ran amok in el-Geneina last year, mainly targeting residents from the non-Arab Masalit community in what human rights groups, including UN experts, have described as ethnic cleansing and possible war crimes and crimes against humanity. Human Rights Watch concluded it was a possible genocide.

The Sudanese army has also come under sharp criticism. Arab civilians were also reported to have perished in this turmoil, many from shelling by army tanks, or in blistering air raids.

Both the RSF and the SAF deny accusations of war crimes and point accusing fingers at their rivals.

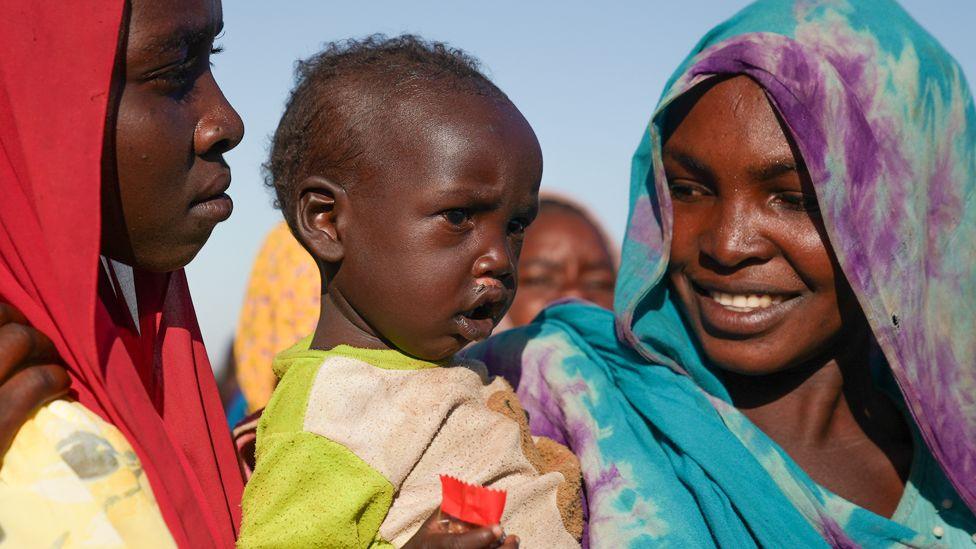

Many Sudanese have fled across the border from el-Geneina to Chad

Few journalists have made it to el-Geneina to see its plight, including the aftermath of what were two massacres over a period of several months last year, which the UN says killed up to 15,000 people.

The frenzy of violence, rape and looting is regarded as one of the worst atrocities in Sudan’s brutal conflagration, which has created the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

We travelled from the Chadian border town of Adre, with the UN delegation, on a journey of less than an hour on a rippling dirt track enveloped in dust, which slices through the desolate semi-desert plateau dotted with half-built or abandoned clay-brick buildings.

A small number of hulking lorries packed with the aid of the UN’s World Food Programme, as well as rickety Sudanese carts driven by horses or donkeys, go back and forth across a border marked by not much more than a few wooden posts and ropes.

But on the other side of the frontier, across the no-man’s land in a dry sloping wadi and along our bleak route, gun-toting RSF fighters in camouflage uniforms patrol this part of Sudan. Some are just young boys who flash cheeky grins.

But, before we left Adre, knowing how hard it may be to gather testimonies inside, we spent time in the sprawling informal camp run by the UN and Chadian authorities close to the border. A throng, mainly women of all ages, some cradling children, fill the vast field. It’s a temporary settlement of startling proportions.

Everyone we spoke with was from el-Geneina. And they all carried their stories with them as they escaped acute hunger and the horrors visited upon their homes.

“When we fled, our young brothers were killed,” piped up a self-assured 14-year-old Sudanese girl in a rose pink headscarf, who spoke calmly and quietly about terrifying times.

“Some of them were still breastfeeding, too young to walk. Our elders escaping with us were killed too.”

I asked her how she managed to survive.

“We had to hide by day and resume our journey in the middle of the night. If you move during the day, they will kill you. But even moving at night is still so dangerous.”

Her family finally made the hard choice to leave their homeland. Her mother was with her but she didn’t know where her father was.

“Kids were separated from their fathers and husbands,” shouted an elderly woman whose dark eyes blazed with anger.

“They indiscriminately killed everyone – women, boys, babies, everyone.”

“We used to get food from our farms," chimed in another woman as their stories tumbled over each other.

“But when the war began, we couldn’t farm and the animals ate our crops, so we were left with nothing. “

Civilians in el-Geneina got a rare chance to tell the UN of their desperate plight

In el-Geneina, our first stop is a modest health centre in the al-Riyadh displacement camp, where Sudanese women in brightly coloured veils sit in chairs along the wall, or huddle on bamboo mats on the floor.

A delegation of mainly elderly men, some with crutches, sit closer to the front under the shade of the corrugated metal roof and wide-boughed trees which frame an open wall.

It feels like a different el-Geneina. There's no visible presence of armed RSF men in a leafy neighbourhood lined with humble mud houses. Young boys turn cartwheels, women in vivid head-to-toe veils walk purposively past, and donkey carts ferrying water drums trot along dusty dirt roads.

“We have suffered a lot,” underlines a community elder, a white-turbaned teacher who is the first to address the visiting UN team in their signature blue vests. He speaks precisely and carefully.

“It’s true that when the war started some people supported SAF, and some supported RSF. But as displaced people we are neutral and in need of every kind of assistance.”

Sudan's 'invisible crisis' - where more children are fleeing war than anywhere else

- Published27 November 2024

'Our future is over': Forced to flee by a year of war

- Published6 September 2024

This camp was first established in 2003, a reminder that Darfur's agony erupted two decades ago when the infamous Arab militia known as the Janjaweed sowed terror among non-Arab communities and was also accused of multiple war crimes. It gave rise to the RSF.

The teacher listed a catalogue of basic needs – from food for malnourished women and children, to schools and clean water. He also explained that most women are now in charge of their families.

Some of the young women, only their eyes visible, film the meeting on their phones, perhaps wanting some record of this rare event.

Mr Fletcher addressed them directly.

“You must often feel that no-one is listening and that no-one understands what you have endured, more than anyone else in the population, and maybe more than anyone else in the world.” They respond with vigorous clapping.

The UN's next stop, behind closed doors, is even more forthright when Mr Fletcher and his colleagues sit in front of a gathering of Sudanese and international NGOs based in Darfur who are struggling to respond to this enormous catastrophe.

Unlike the UN, they haven’t waited for permissions from Gen Burhan’s government to operate here; approval for the UN’s international staff to be based here was recently revoked.

Twenty NGOs, working without reliable internet or electricity or even phones, and struggling to obtain more Sudanese visas for staff, say they’re trying to help the 99.9% of the population in need. Their message was clear – the UN system was failing them.

The WFP has struggled to get much-needed aid into Sudan

“More needs to be done,” Tariq Riebl, who heads the Sudan operations of the Norwegian Refugee Council, tells us after the meeting. But he says his worst fear “is that no-one cares, that they’re only paying attention to other crises such as Ukraine and Gaza”.

“This is one of the worst conflicts we've seen in recent memory, in terms of the violence that's been committed, and people fleeing,” he emphasises.

“And there are also very few actual famines anymore, but this one is one.”

So far, the global Famine Review Committee (FRC) has declared it in one part of the Zamzam displacement camp housing about half a million people in North Darfur; more than a dozen other areas are said to be on the brink.

“The UN can't just charge across the border anywhere we would like to,” insists Mr Fletcher.

“But this week we’ve got more flights coming in to regional airports, more hubs opening inside Sudan, and we're getting more people on the ground as well.”

During his week-long visit to Sudan and its neighbours, he met representatives of both the SAF and the RSF to push for more access across lines and across borders.

He started his new job vowing “to end impunity and indifference”.

“It would be rash to say I can end impunity alone,” he remarks diplomatically about a conflict in which rival regional powers have been arming and assisting the warring parties.

The United Arab Emirates is accused of backing the RSF, although it denies this. While countries including Egypt, Iran, and Russia are known to be supporting the SAF. Others are also weighing in, including Saudi Arabia and regional organisations including the Arab Union, with all sides saying they’re working for peace, not war.

When it comes to indifference, after Mr Fletcher's first visit many more Sudanese and aid workers will be watching closely, hoping he can make a difference in this "toughest crisis in the world".

More BBC stories on the Sudan crisis:

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external