Revamped Burrell named Scotland's best building

Judges described the transformation as the "rejuvenation of an old friend"

- Published

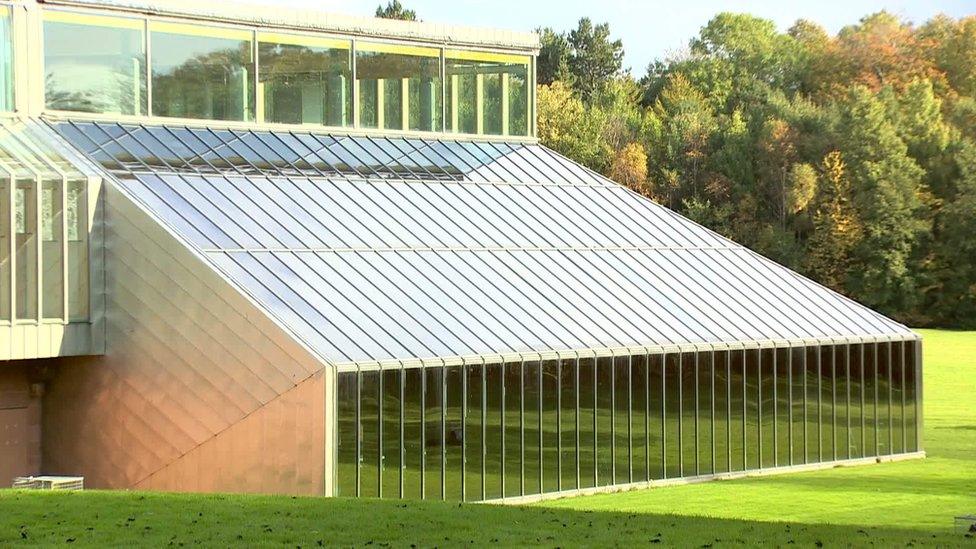

Glasgow’s Burrell Collection has been named winner of the Andrew Doolan Best Building in Scotland award.

The award, given annually by the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS), was collected by John McAslan + Partners who carried out the £68.25m Burrell Renaissance project.

Judges said the project was “an outstanding example of problem solving and future proofing that has rejuvenated an old friend”.

It is more than a decade since Mr McAslan and his London-based practice was first asked to consider a revamp of the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

The Burrell Collection reopened after a five-year refurbishment

The A-listed building houses the collection of shipping magnate Sir William Burrell. Gifted to the city of Glasgow in 1944, it took almost 40 years to find the right location, thanks to the industrialist’s stipulation that it should be far from the city centre and the pollution which might damage priceless artworks.

Opened in 1983, it turned out to be natural elements which caused most harm, with rain leaking through the flat roof onto the galleries below.

The challenge was to make repairs and revive interest in the collection without compromising the integrity of the original design, not least because the original team of John Meunier, Brit Andresen and Barry Gasson were still around.

They too had taken more than a decade to reach their goal, having won a competition to design the museum in 1971.

- Image source, Hufton and crow

Image caption, The Burrell at dusk makes a striking figure

1 of 7

“The first challenge was to understand the original building,” John McAslan said.

“What was important to the new original architects and what was critical to save, like the walk in the woods, that magnificent gallery on the north side of the building.”

“We had to understand how it was made and respect that. At the same time, we had to consider simple practical things like the leaks, and making it air tight.

"And then we were able to create some modest interventions to enhance the building while respecting what was here.”

One of those interventions is the central staircase which links the new basement space to the upper galleries.

“This replaced a lecture theatre where no one visited,” said Mr McAslan.

“It’s essentially a set of steps, linking the café with the galleries but as it’s being used today it’s now a place for people to convene and talk.”

'Modern comprehensive school'

Another challenge was the timing, which meant the museum was due to open in 2020, just as the pandemic struck.

“It was hard, especially for the contractors who worked through the pandemic as much as they could. The building was finished on time, and pretty much on budget but we had to wait.”

It is not unusual for larger projects – like King's Cross Station – to take many years to complete, but Mr McAslan said the delays meant a number of their supporters were not there at the end, including former Glasgow Life CEO Bridget McConnell, who has retired, and Sir Angus Grossart who died in 2022.

“This has been a collective project so the award is for everyone involved, 15,000 people in the local community, there are a lot of people involved,” Mr McAslan said.

John McAslan accepted the award on behalf of his firm John McAslan + Partners who carried out the £68.25m Burrell Renaissance project

John Meunier, who was part of the original architecture team, was not impressed by the changes. He described the space as “the sort you might see in a modern comprehensive school”.

He also disliked plans to add another entrance beyond the original 16th century stone archway embedded in modern brick.

But an increased number of visitors to the Burrell Collection suggests the public disagrees.

John McAslan spent the first few days after the museum opened just observing people.

“I think it’s been mostly favourable. The most successful projects are those where visitors are aware something has changed but it’s pretty much the same and that was the reaction.

"People found it familiar but it was easier to navigate and the collections were more engaging, especially for kids," he said.

King Charles opened the reworked building in October 2022

The Andrew Doolan Best Building in Scotland award was first set up in 2004 in memory of an Edinburgh-based architect and developer.

But 20 years on, his family are unable to continue providing a cash prize. RIAS, which administers the award, hopes to find a new sponsor.

In the meantime, John McAslan is proud to accept the honour of the Burrell being named Best Building of the Year.

“The cash isn’t really relevant,” he said.

“It’s the title of building of the year that’s important and if it stimulates debate especially about repurposing buildings, that’s important. And not just cultural spaces, what about tower blocks and other buildings? Why demolish, when you could give them a new life.”

Another smaller example of his passion for repurposing buildings is Dunoon Burgh Hall.

He, his wife and the community raised the funds needed to restore the derelict 19th century space into a community arts centre, which opened officially in 2017.

“That took ten years and I have been looking for another Dunoon Burgh Hall since then," he said.

“I want to find a building which with a little bit of money and community backing can be brought back to life.”

Related topics

- Published12 July 2023

- Published1 June 2017

- Published29 March 2022