How is the world doing on tackling climate change?

The recent floods in Valencia, Spain, were made worse by climate change

- Published

Scientists, politicians and world leaders are meeting at the annual UN climate summit, COP29, in Azerbaijan during what is set to be the hottest year on record.

What progress have countries already made to tackle change?

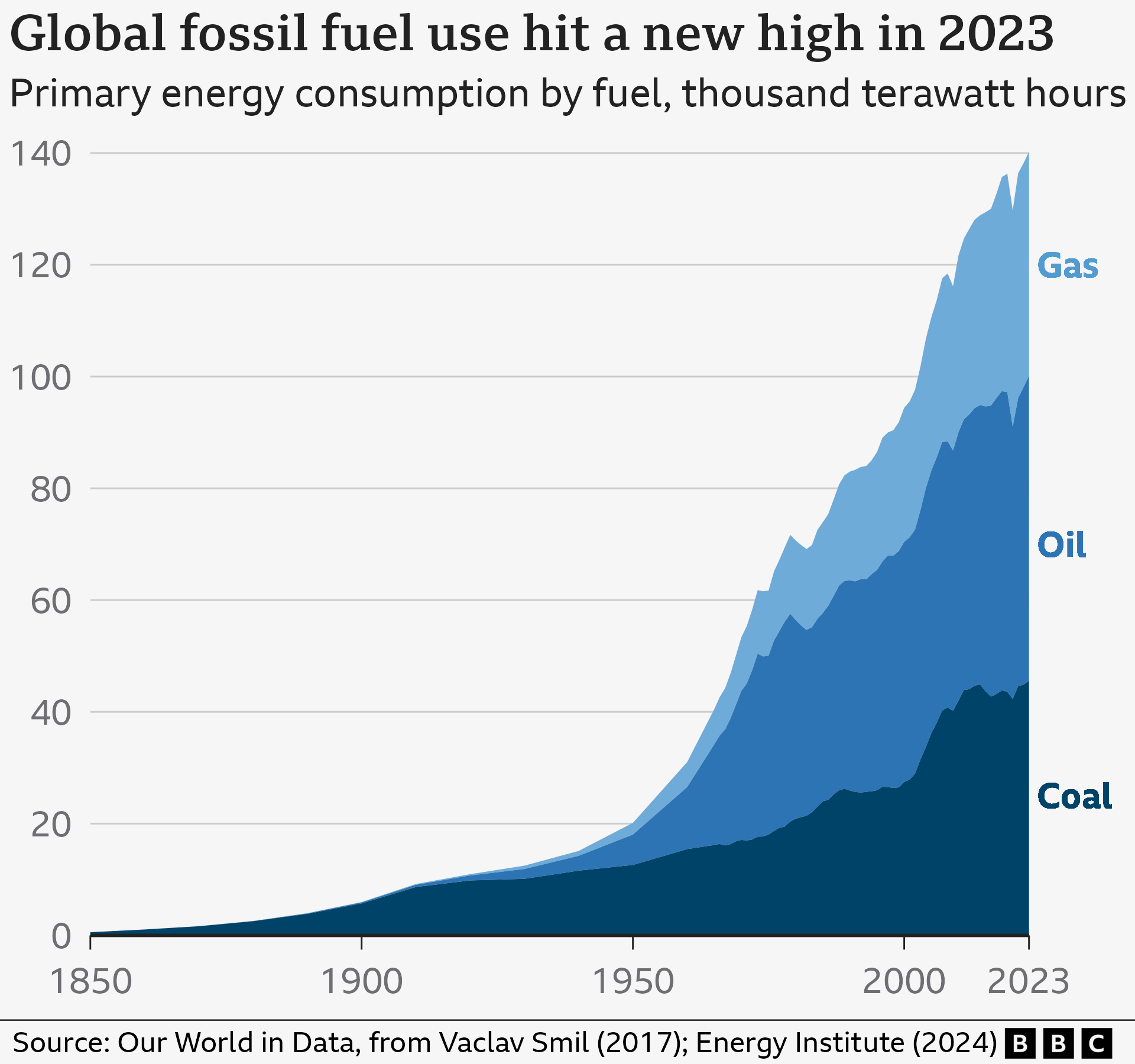

Fossil fuels: Still increasing despite pledges

Fossil fuel use is still rising despite positive steps by some countries including the UK and by the EU to wean themselves off the energy sources that do most to heat up our planet.

At last year’s COP28 meeting in the United Arab Emirates, countries agreed to "transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems".

Perhaps surprisingly, this was the first time that the world had taken direct aim at coal, oil and gas. These are the main drivers of climate change because they release planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) when burned for energy.

But in fact, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels are projected to reach a new high in 2024 at 37.4bn tonnes, up 0.8% from 2023, according to research by the international Global Carbon Project team.

“The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly dramatic, yet we still see no sign that burning of fossil fuels has peaked,” said lead author Prof Pierre Friedlingstein of the University of Exeter.

There have been some signs of progress.

The UK closed its last remaining coal power station in September, proving that electricity in major economies can still flow without the dirtiest fossil fuel.

In the EU, the share of electricity coming from coal, oil and gas reached a new low earlier this year.

But new fossil fuel projects are still being approved in many countries. Of the world's biggest economies, China is a major culprit, but far from the only one.

This is despite warnings from the UN that, if all the coal, oil and gas from existing and under-construction projects were burned, the world would likely warm far beyond the globally agreed target of 1.5C.

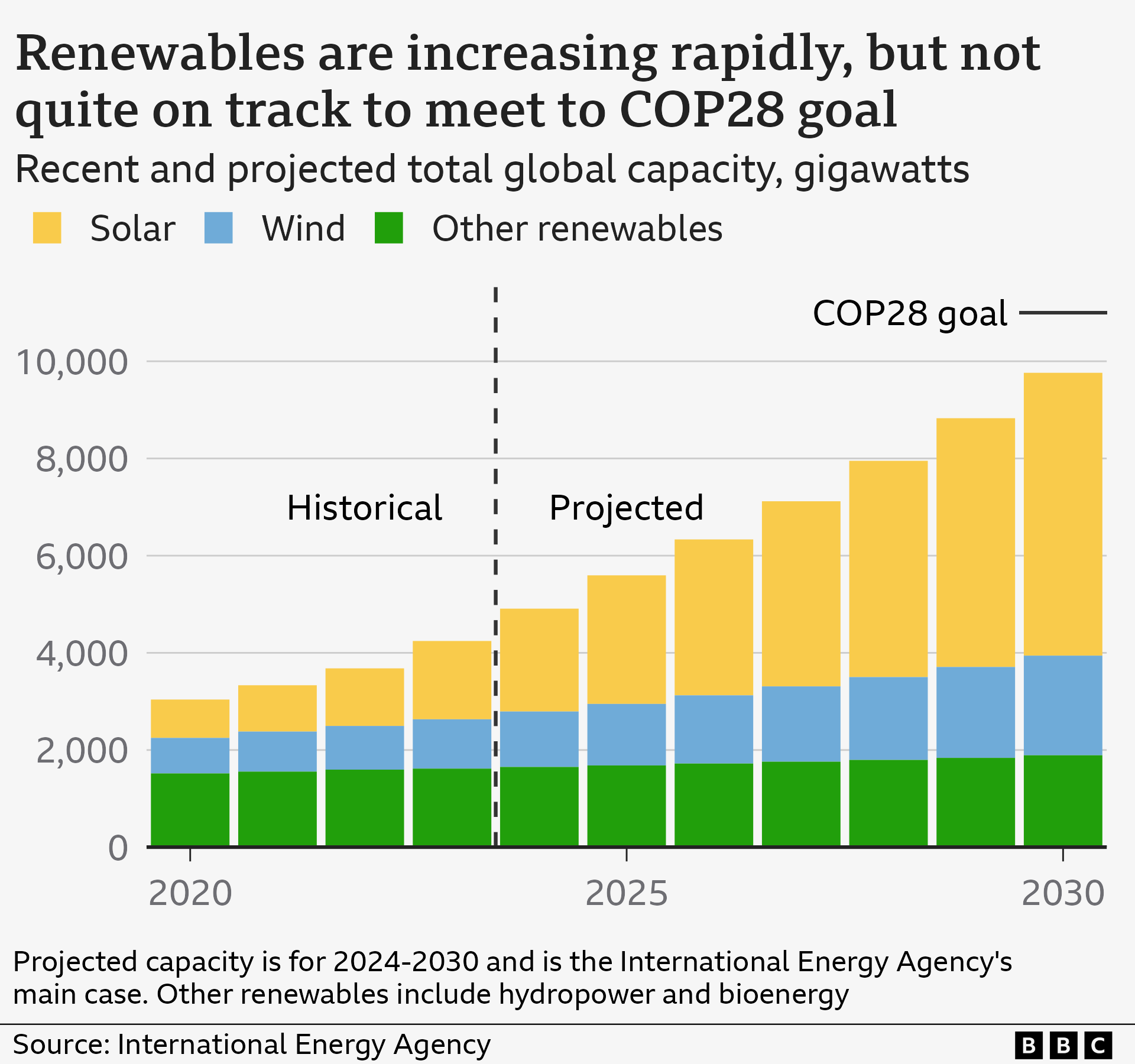

Renewables: Rapid growth is encouraging

Wind and solar power have increased massively and are getting cheaper

Renewable sources of energy like wind and solar are growing very quickly and prices have fallen considerably over the past decade.

Last year, countries promised to triple the capacity of so-called 'renewables' by 2030.

The idea is that these clean sources should start to displace dirty fossil fuels in the electric power grid, therefore reducing CO2 emissions even as electricity demand grows.

Currently, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global renewable capacity to grow 2.7 times by 2030 compared with its 2022 level - so not quite on track for a trebling, but close.

The hope is that economics, as much as climate policy, can help renewables to grow even faster.

“In many cases and for many countries, renewable energy is already the cheapest and the economically sane option for producing energy,” said Prof Joeri Rogelj of Imperial College London.

China alone is expected to account for more than half of the growth in global renewable capacity to 2030, according to the IEA. But renewables are also set to rise quickly in the EU, US and India, as well as the UK.

Batteries and other forms of energy storage are key to the expansion of renewables: while a fossil fuel-driven power station can be fired up at any time of the day, the wind doesn't always blow and the Sun doesn't always shine.

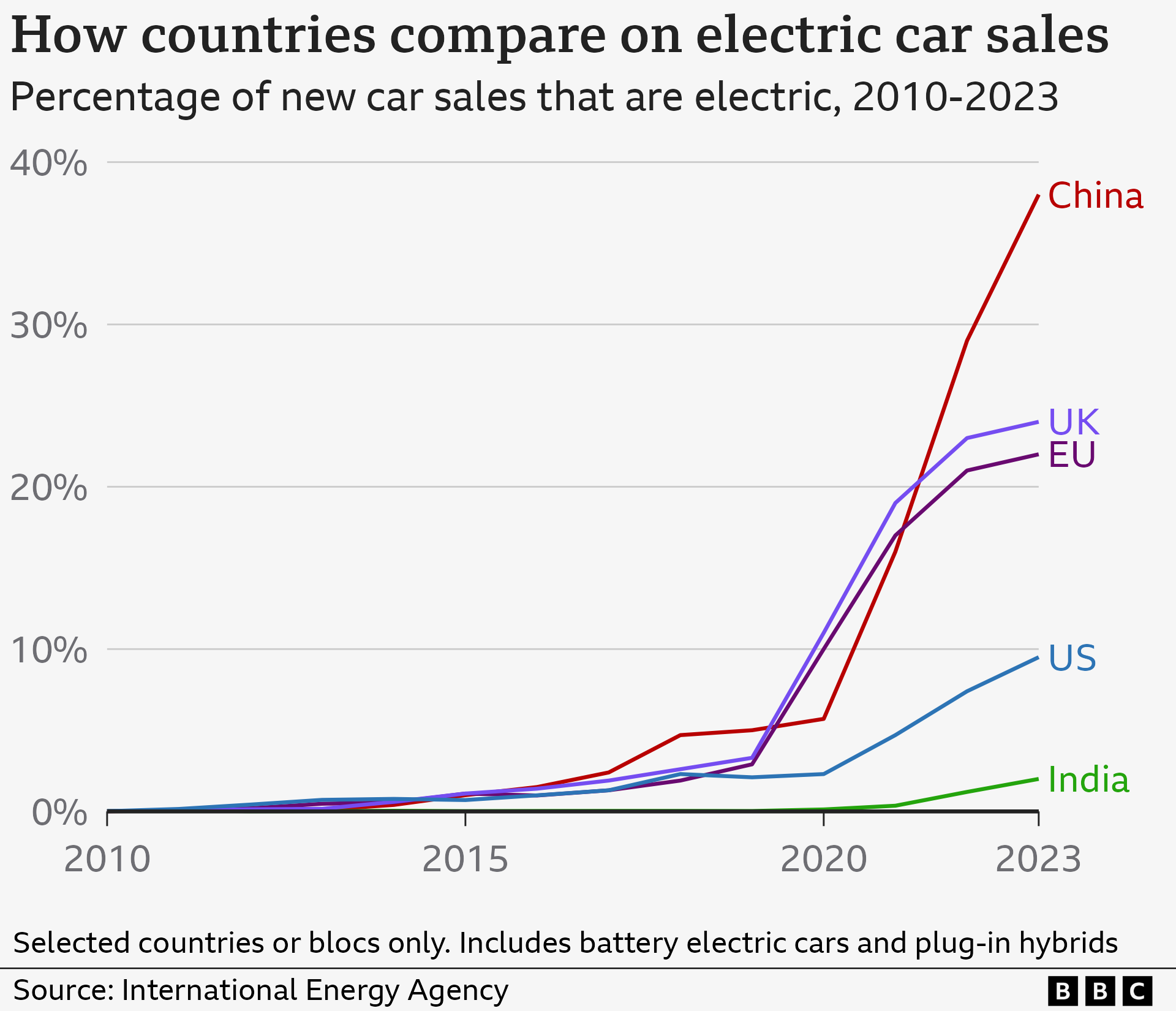

Electric vehicles: Numbers rising but it's a mixed picture

The number of electric vehicles (EVs) is growing quickly, led by China, but rates of uptake vary considerably between countries.

They are the main way to reduce planet-warming emissions from road transport, according to the UN.

That is because they can be powered by clean electricity, rather than directly from fossil fuels.

The cost of EVs differs widely between nations.

In China, the IEA estimates that more than 60% of electric cars sold in 2023 were already cheaper than their petrol or diesel equivalent, partly thanks to government subsidies to the industry, encouraging more people to make the switch.

In other regions, electric cars have typically been more expensive, but are generally getting cheaper.

In the UK, for example, the recent growth in EV sales is partly thanks to obligatory government targets, explained Colin Walker, head of transport at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit.

"As prices are driven down, more families are able to access the savings that come from electric driving," he said.

Deforestation: Mixed progress

The Amazon sucks up carbon dioxide, so protecting it is vital

Deforestation fell significantly in Brazil's Amazon in 2023 but the world remains far off track to meeting its target of halting it by 2030, according to the World Resources Institute.

There have been some encouraging signs. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva came back to power in 2023, recommitting to that goal and promising to tackle tree loss. His predecessor Jair Bolsonaro had significantly weakened legal protections for the forest.

This is a region that has historically helped to buffer the world from further warming, by absorbing some of the carbon dioxide produced from human activities.

But there are concerns that this is changing as a result of tree losses and the effects of drought worsened by climate change.

Deforestation increased in other parts of the Amazon, including the part in Bolivia.

“We must learn from the countries that are successfully slowing deforestation,” said Mikaela Weisse, Global Forest Watch Director at the World Resources Institute.

Claudio Angelo from Brazil's Climate Observatory said that in the case of his country, while measures like punishing people for felling trees had been successful it was also important to focus on promoting things like sustainable agriculture.

"Brazil has been very good at the stick so far, but with the carrot we haven't been that good," he said.

So what's the big picture?

While a lot of positive steps have been taken, the headline figures on emissions have sadly not changed much.

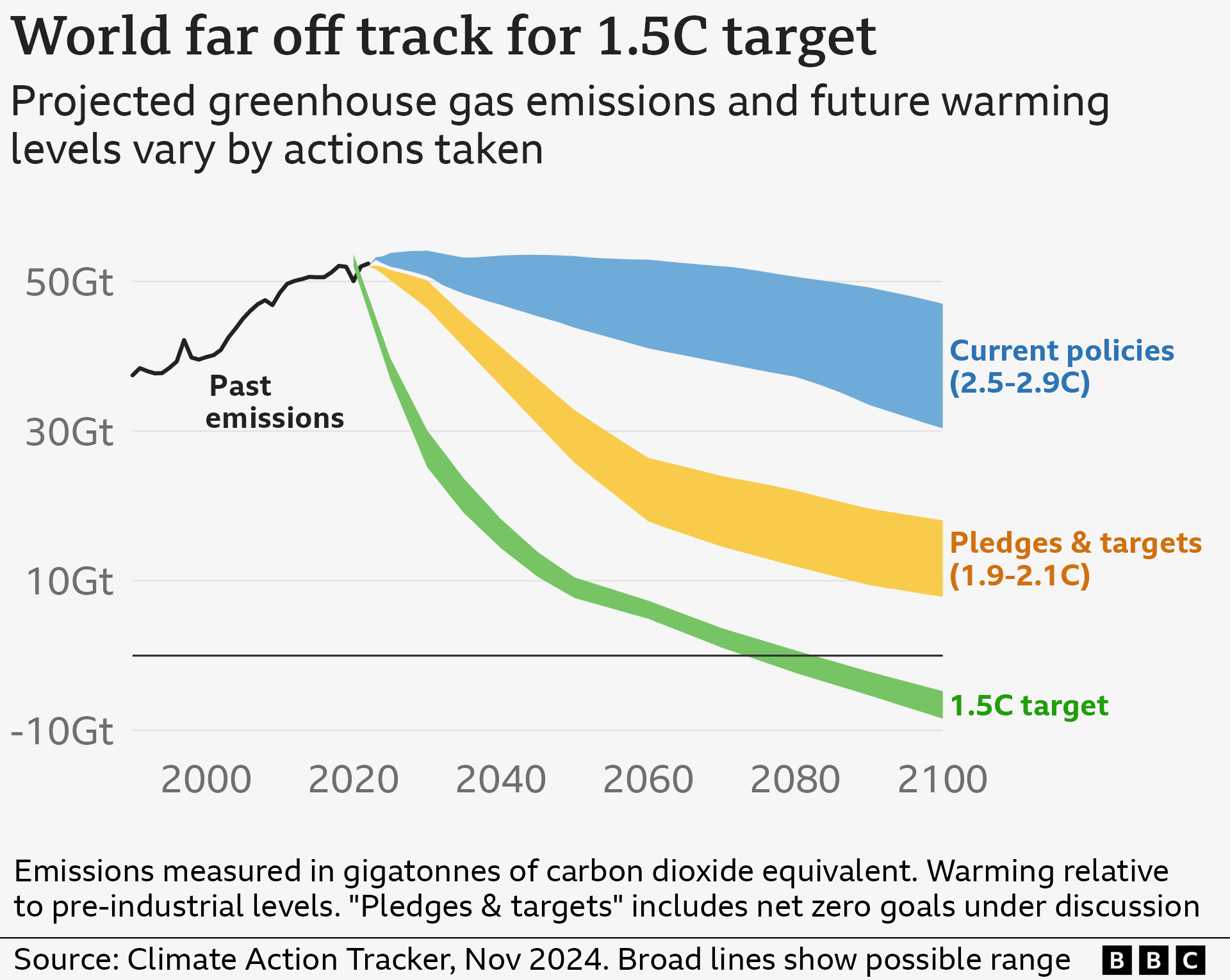

A recent UN report warned that current policies put the world on track for around 3C warming by the end of the century. Other organisations have come up with similar figures.

This is clearly far above the target to try to limit long-term warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, which was agreed by nearly 200 countries in Paris in 2015.

The UN says that the 1.5C target is still “technically possible”, but only with huge cuts to emissions over the next decade.

The recent US election has also posed challenges for uniting the world around new climate targets. Incoming president Donald Trump has pledged to withdraw the US from the Paris climate agreement and “drill, baby, drill” for more oil and gas.

This is “a major blow to global climate action," according to Christiana Figueres, the former UN climate chief.

"But it cannot and will not halt the changes under way to decarbonise the economy and meet the goals of the Paris agreement.”

Related topics

More on COP29

- Published15 November 2024

- Published15 November 2024