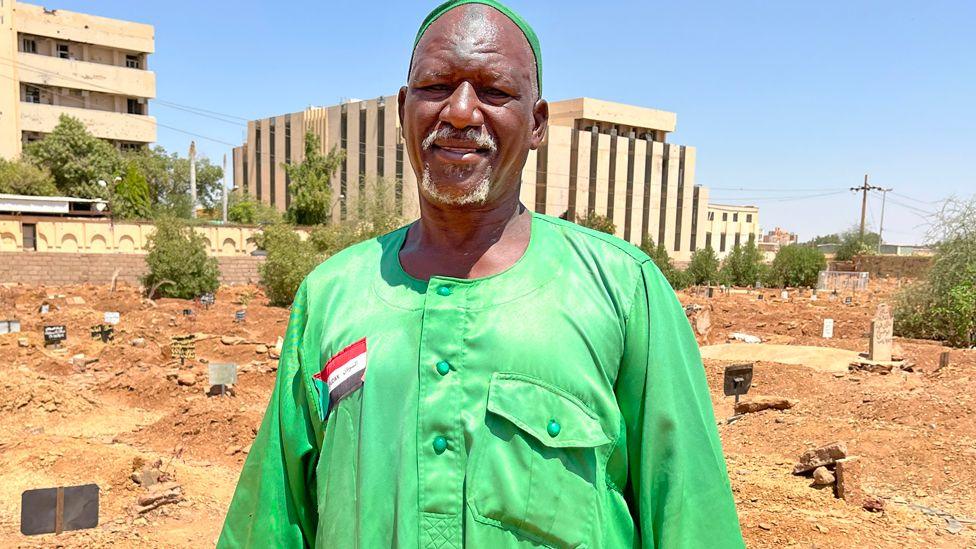

The gravedigger 'too busy to sleep' as Khartoum fighting rages

Abidin Durma, well-known as the gravedigger of Omdurman, says he and his volunteers bury up to 50 bodies a day

- Published

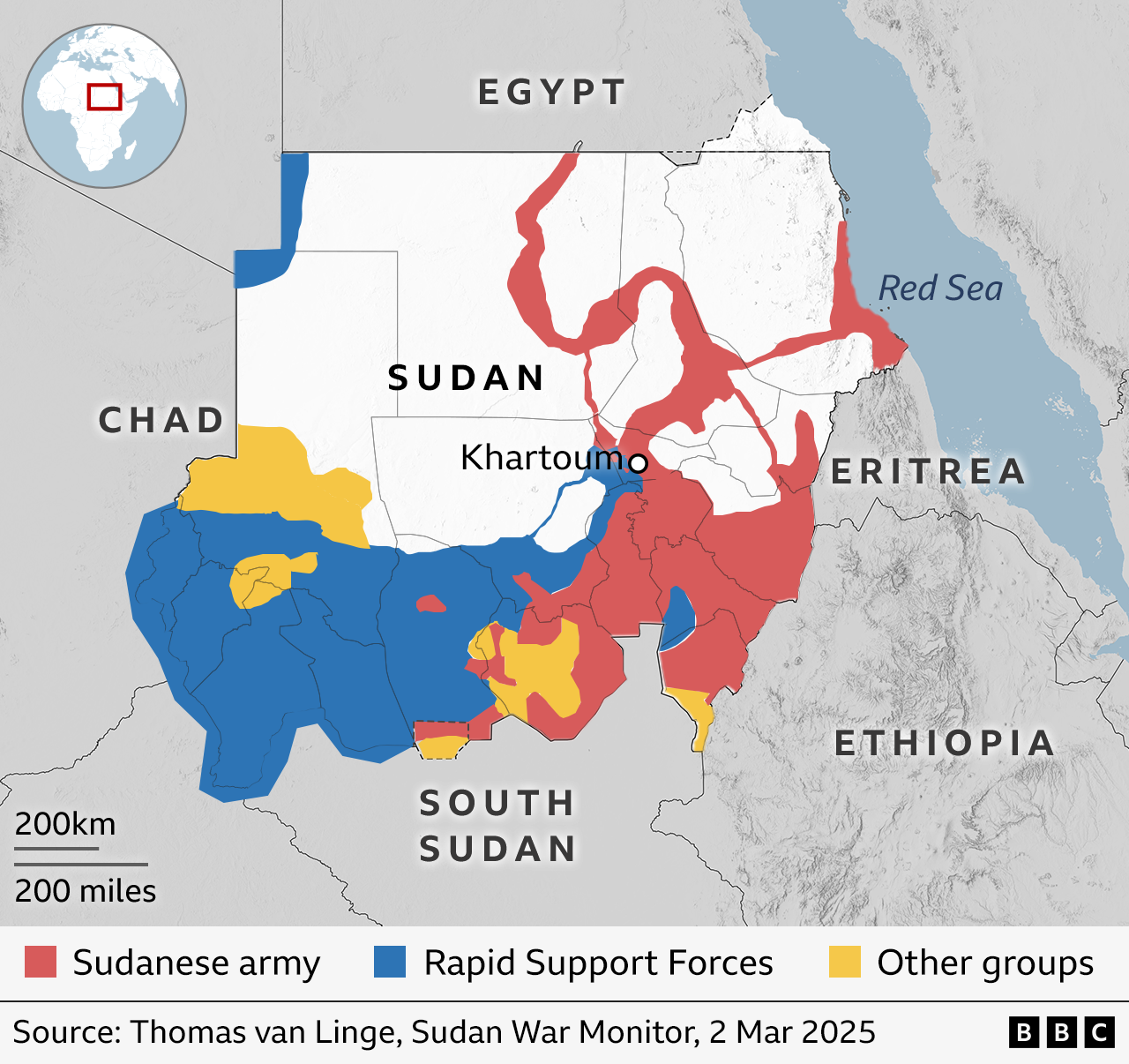

After retaking the presidential palace Sudan's army appears poised to regain control of the capital, Khartoum, two years after it was ousted from the city. As the soldiers were preparing to launch the latest offensive the BBC was given rare access to the operation.

Sudan's people continue to bear the brunt of the war, which has inflicted massive death, destruction and human rights violations on civilians, and driven parts of the country into famine.

In recent months troops had recaptured northern and eastern districts of the capital, and pockets of central Khartoum.

The latest offensive to expand that foothold began a week ago.

We were taken to a rallying point in Khartoum North in the middle of the night.

The BBC filmed soldiers in Khartoum preparing for an offensive on the city centre

Troops were in high spirits, singing chanting and whooping as they built momentum for the battle.

By morning the army had advanced. By evening of the next day, it had broken through a key central zone held by the RSF, allowing troops in the south-west of the city to join forces with the military headquarters to the north.

On Thursday the army destroyed an RSF convoy trying to withdraw south from the presidential palace, according to reports.

Footage apparently released by the military showed drones targeting vehicles, and a massive fire, possibly caused by the explosion of ammunition transported by the RSF fighters.

The strategically located Republican Palace complex is the official residence of the president and has historical and symbolic significance in Sudan.

By Friday morning, the army had captured the palace, though the RSF said they were fighting back.

The smell of death lingers in the air Ahmed Sharfi Cemetery where there are row after row of brown earth mounds - some marked, some not

One person undoubtedly cheering on the troops is Abidin Durma, well-known as the gravedigger of Omdurman, a sister city to Khartoum over the River Nile that is part of the capital region.

He is clearly a strong patriot, regularly referring to what he calls "the war of dignity".

But he also experiences daily its high cost for civilians.

Mr Durma's ancestors were related to the Mahdi, a 19th Century leader who created the foundations of the Sudanese state and an influential religious movement.

They established the Ahmed Sharfi Cemetery, one of the oldest and biggest in Omdurman.

Now the graveyard Mr Durma has tended for decades paints a vivid picture of the scale of death.

It has expanded on three sides by roughly 10 acres (four hectares), with row after row of brown earth mounds, some marked, some not.

The smell of death lingers in the air above them.

Mr Durma tells me that he and young volunteers bury "not less than 25, 30 or 50 bodies per day".

That is partly because other cemeteries became unsafe during active fighting in Omdurman, the city is crowded with displaced people, and the health system has been overwhelmed by conflict.

Bodies have to be buried as soon as possible as there is no longer reliable refrigeration at the morgue

But artillery fire has claimed a large number of lives.

Mr Durma showed me a mass grave for victims of a strike on a school.

One entire section of fresh graves holds bodies of those killed in the shelling of a main market in January: at least 120 people died.

We are told the RSF is responsible, firing into army-controlled areas of Omdurman. But both sides are condemned for war crimes - the military is accused of mass killings elsewhere.

Bodies come straight from the hospital, which calls the grave digger to let him know he needs to prepare for burial. The process is efficient, and fast.

"We bury them right away, because there is no [reliable] fridge," Mr Durma says.

"The graveyard is safe. The graves are ready. The bricks are ready. The people who bury are ready, inside the graveyard."

"There is no time to sleep until the last body is buried," he adds, "and then I sleep for half an hour or 15 minutes, until I get another call. I come back like now, and three, four bodies arrived.

"People die from bullets, from shelling. People are killed sitting in their homes. There is so much death."

His phone rings again. Another body is ready for burial.

Omnia, held here by her uncle, was recently orphaned - she was in her mother's arms when a shell hit their neighbourhood

Prayers for the dead have become a regular ritual in al-Mabrouka, a neighbourhood in the western al-Thawra district of Omdurman that is in the line of fire between the army and the RSF.

A group of friends gather around Abazar Abdel Habib at the local mosque to offer condolences, lifting their hands as they recite verses from the Quran.

We had met Mr Abdel Habib at the hospital morgue the previous day, where he was picking up the bodies of his brother and sister-in-law. They had been struck by artillery fire while taking their son to pre-school.

At the family home, a little girl, Omnia, woke up crying, in pain.

She was in her mother's arms when the shell hit, and escaped with only a foot injury. Her survival is seen as a miracle.

She has been orphaned along with three brothers.

"We'll tell them exactly what happened, about the shelling and the war," says Mr Abdel Habib, cradling Omnia.

"They are the generation of the future, we will not allow this to affect them in the future. We will try to make up to them the affection of their mother and father, even though it's hard. But this is destiny."

I joined women from the community who had crowded into a nearby room to mourn the dead, as they have done many times during this war.

Three other people were killed in the shelling that same day, including two young boys.

Daily we are losing our children. The students cannot settle, there is no studying. There is always a state of fear - we are always in a state of sadness"

Nothing like normal life is possible, they told me.

"We hide under the beds when the shelling starts," says Ilham Abdel Rahman, when I asked her how she protects her children.

"One hit our home and killed the neighbour's girl at the steps of our door."

Hawa Ahmed Saleh says if there is shelling early in the morning "we go to the market after that to buy food".

"If it doesn't happen, we're forced to sit and wait until the shelling comes, and after it stops, people will go and gather what they need for living.

"The children are always in a state of terror," she adds.

"Daily we are losing our children. The students cannot settle, there is no studying. There is always a state of fear, we are always in a state of sadness."

If the army does regain full control of the capital, at least here the shelling will stop.

But the war will continue elsewhere in the country, and its wounds will haunt Sudan for years to come.

More on Sudan's civil war:

'Tortured and terrified' - BBC witnesses the battle for Khartoum

- Published14 March

The two generals fighting over Sudan's future

- Published17 April 2023

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external