The ever-growing power of China’s Xi Jinping

- Published

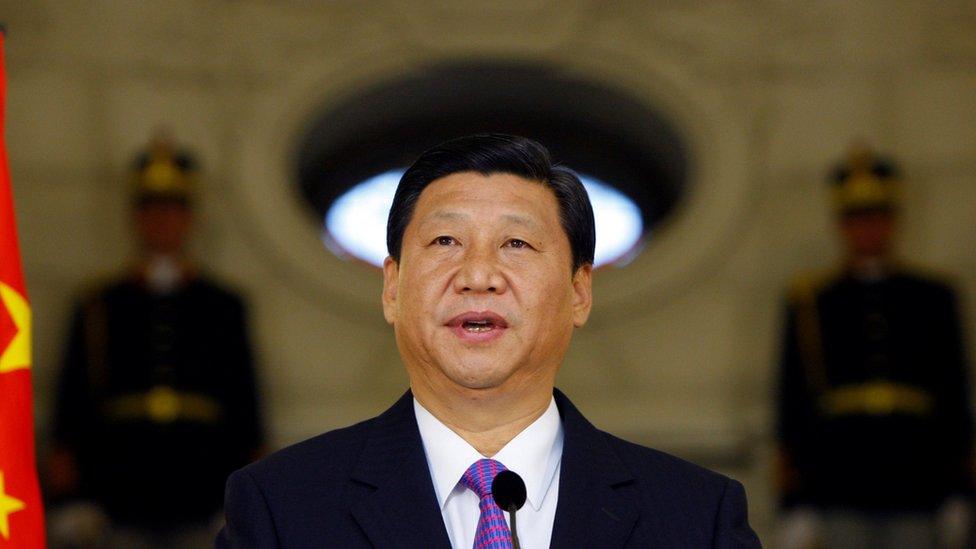

Chinese President Xi Jinping

At the beginning of this week China's leader Xi Jinping was not officially "at the core" of the Communist Party. Now he is. Why should that matter? Because, in China, little words have big meanings.

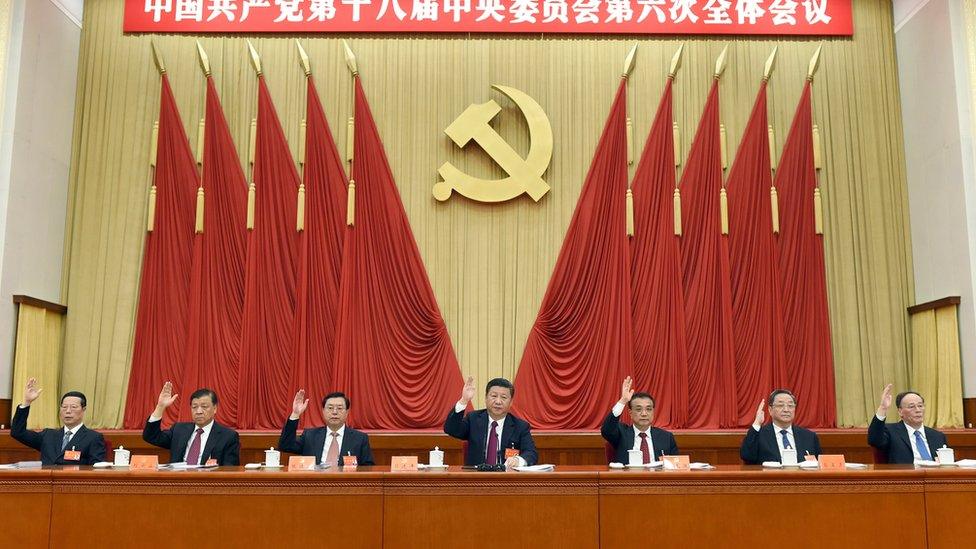

Over four days in the Chinese capital a major political meeting has been taking place between a couple of hundred members of the Central Committee. It is known as the Plenum.

Such gatherings are usually held once a year and allow the Communist Party to make policy decisions which are later shoved through the National People's Congress for approval.

At this week's Plenum, it was pronounced that Party members should unite around the Central Committee "with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core".

Communism's 'core'

The expression is already falling off the lips of senior government officials like a religious mantra. There they were at a press conference explaining the plenum decisions and describing concepts as being in step with "socialism with Chinese characteristics" in order to boost the standing of the Communist Party "with Xi Jinping as the core".

A more mind-numbingly dull and uninformative press conference you would struggle to find, even in China. Pre-ordained questions, pre-scripted answers.

Yet, even amongst the hours of dross, there was this significant new development. "Bla bla bla… Xi Jinping as the core… bla bla… with Xi Jinping at its core… bla bla… Xi Jinping: core… Xi Jinping: core".

Chinese President Xi Jinping is at the core of his country's communist party

What worries China observers is that General Secretary Xi is growing into an untouchable figure the likes of which has not been seen here for quite some time.

This was not the case, for example, with the previous administration of Hu Jintao. Though he too was president and chairman of the Central Military Commission, his was a leadership within a system of collective responsibility. You could imagine a diversity of views amongst the (then nine-member) Politburo Standing Committee.

You cannot imagine that now.

Since 1949 the most extreme example of an omnipotent ruler was naturally Mao Zedong.

When his disastrous policy known as the Great Leap Forward left millions of people starving to death, Defence Minister Marshal Peng Dehuai challenged him. For this, one of the heroes of the revolution was purged.

Naturally the China of today is nothing like it was in 1959 but the accumulation of power around a single figure "at the core" who cannot be criticised is making plenty of analysts concerned.

Discipline commission

The sprinkles of information which have been released regarding this Plenum's decisions mostly relate to the fight against corruption: Xi Jinping's fight against corruption.

Apparently the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection has investigated 1,018,000 officials. Of these 1,010,000 have been punished. Not a bad strike rate.

Because of this rampant fraud, we have been told the rules governing Party behaviour had to be made much more strict.

This was needed in order to stamp out election-rigging, the selling of positions and the practice of bargaining with Party organizations in order to secure a promotion or promotions.

For government officials it is now prohibited to "request an official post, honour or special treatment".

I suppose these types of conversations would be now out of bounds:

Q: "Heh Wang, you know I have always had a great interest in the steel industry. I was wondering if you have found somebody to fill your shoes at Wuhan Steel?"

A: "Well I am not sure but any chance your uncle could help out with that golf course development my family has?" etc.

The idea must now be that you will wait to be asked. I have no idea how you are supposed to show your interest in a particular job (because they would not take any serious questions at the aforementioned explanatory press conference).

Maybe you just do what you are told and develop an expertise in cotton dying machine technology if your Party requires you to?

On this front there is also a rather ominous-sounding new rule amongst those just approved at the Plenum.

'Xi Dada'

For members the disobeying of any decisions made by a Party organisation is now forbidden.

Here is another (rather extreme) hypothetical example:

Person giving order: "Excuse me but we have just decided to use extreme force to clear the remaining protestors out from in and around Tiananmen Square so if you would not mind leading your column of tanks down there to sort them out that would be most appreciated."

Response:"Well gee, to tell the truth I have a few moral qualms about firing on my unarmed civilian countrymen."

Person giving order: "Sorry, disobeying any Party decision is now forbidden."

Anecdotally, President Xi Jinping seems very popular amongst ordinary Chinese people: they call him "Xi Dada", loosely translated as "Uncle Xi".

These same average citizens see officials found to have been corrupt being sent to gaol and are cheering all the way.

There is even a television programme here featuring the confessions of regional bosses admitting their crimes on their way to incarceration.

Chinese call their president "Xi Dada" - an expression meaning uncle

There is a view, though, that so many officials are up to their necks in ill-gotten gains, Xi Dada could have been using a selective anti-corruption campaign to take out only his factional enemies, thus shoring up his own position.

It is a view that we journalists and academics toss about quite a bit. It is not one you will hear expressed amongst the so-called lao bai xing, the average Chinese people. To them, who cares if only certain corrupt officials have been taken down? At least some of them have.

Yet the crackdown has been so widespread it has led to one contentious theory.

If Xi Jiping and his people have punished more than a million officials who all have friends and family where does that leave him in terms of amassing enemies who are biding their time for now?

How dangerous might it be for President Xi to ever give up power? Can he find a mechanism to extend his tenure or at least put a wall around himself? Or maybe he just needs a Medvedev-style supporter to come along as a chosen successor?

We will not know the answer to any of this until the end of his second term in another six years.

- Published24 October 2016

- Published5 February 2016

- Published24 September 2015

- Published23 June 2016