Trump-Kim Summit: Three questions about China's role

- Published

China is Pyongyang's only ally, and Washington's most powerful rival

As the US and North Korea prepare for their historic summit, China is the elephant in the room.

Beijing is Pyongyang's only significant, long-standing ally, as well as Washington's most powerful, long-term strategic rival.

That gives it a huge role in determining whether or not any agreement reached between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un can be turned into success.

As those two leaders hog the limelight, here are three key questions about the powerful player lurking off stage.

What does China want?

In a word, stability.

Answered the other way round, what China most definitely doesn't want is any more nuclear brinkmanship on its border.

It knows only too well Pyongyang's paranoia.

It mistrusts Washington's wildcard president.

And it genuinely fears another war of words leading to military miscalculation and escalation.

With that in mind, a return to diplomacy and dialogue has sometimes seemed like an end in itself for Beijing.

But while China's patience with North Korea has been seen to be wearing thin in recent years, it is still an old ally, and America is still a common strategic rival.

It is likely to be far more pragmatic about the possibility of Kim Jong-un unilaterally negotiating away his hard-won nuclear deterrent.

And if Mr Kim is able to win any concessions from Mr Trump - any shift in the US military posture on or around the Korean peninsula for example - China will see an advantage for itself of course.

How much influence does China wield over North Korea?

Some.

China accounts for up to 90% of North Korea's trade with the outside world.

But China has not forced North Korea to the negotiating table.

Barbed wire and smuggled crabs: Watching North Korea from China

Beijing may have signed up for the toughest sanctions ever against its neighbour, but it did so arguing, with some logic, that the more economically isolated Pyongyang becomes, the more the regime is incentivised to pursue its strategy of nuclear deterrence.

Kim Jong-un is off to Singapore on his own terms and for his own strategic reasons.

Instead, China's sanctions enforcement serves mainly Chinese purposes.

The goodwill generated can be traded in its wider, geopolitical contest with America.

And it has the limited, but still useful effect of reminding North Korea that it can't ignore Chinese interests entirely.

The effect is limited, of course, because North Korea knows that China fears an economic collapse on its border much more than it fears the nuclear status quo.

It's is a classic case of the tail wagging the dog.

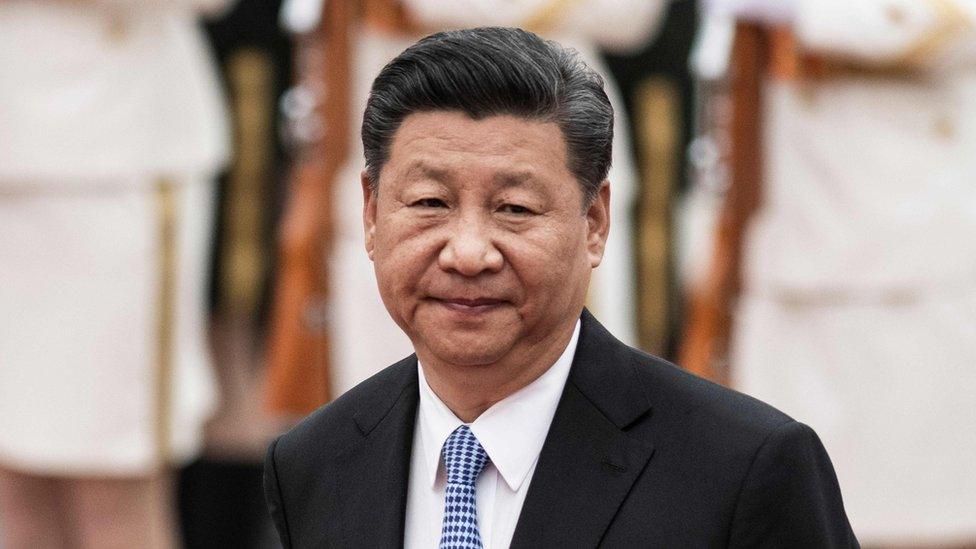

Remarkably, President Xi and Chairman Kim met for the first time just three months ago, and they've met again since.

Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un have now met twice

The two meetings came only after the Trump-Kim summit was announced.

Was this flurry of diplomacy, some analysts wondered, a sign that China was desperate not to be sidelined?

There are suggestions that the sanctions are suddenly easing a bit.

And Donald Trump has also hinted that China has begun meddling.

"I will say I'm a little disappointed", he said, "because when Kim Jong-un had the meeting with President Xi... I think there was a little change in attitude from Kim Jong-un. So I don't like that."

What will China do if the summit fails to deliver?

For China, success will be anything - a treaty, a roadmap, a warm handshake and a vague plan - that keeps the dialogue going.

From its perspective, the most significant thing about the young North Korean leader is not any ambiguous talk of denuclearisation, but his fledgling, domestic economic reforms.

Last month, according to the Chinese foreign ministry, a senior North Korean delegation visited Beijing "to learn about the achievements of China's domestic economic development".

This has always been China's preferred model.

Could the recent demolition of North Korea's nuclear test indicate that the country is moving away from its status as a isolated pariah state?

It would not be a disaster, perhaps, from China's point of view to see North Korea (with its limited nuclear stockpile) locked into a never-ending set of disarmament negotiations while Chinese businesses get on with the job of building infrastructure and expanding trade.

It's the "Chinese dream" made for export; stability through prosperity, with of course a good measure of lasting authoritarianism thrown in.

Zhao Tong is a North Korea expert at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre in Beijing.

"Regardless of how much nuclear progress is made during the summit, China has a more important long term strategic goal," he told me.

"Which is to help North Korea grow its economy and transform itself from isolated pariah state into a more normal and more open country."

But if the summit runs off the rails, if there's a return to the US talk of limited military strikes, China may push on with its plan anyway.

North Korea has its bomb and is now clearly in statesman mode.

Displays of North Korean "restraint" would not be lost on China and if talks collapse, it would be likely to point a finger of blame not at Mr Kim, but at Mr Trump.

"If the United States walks out of the summit and goes back to the maximum pressure campaign, China would blame the United States for the failure of diplomacy," says Mr Zhao from the Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre.

"And if the US shows any willingness to launch a military strike to disarm North Korea it's possible I think China would try to mobilise its own forces to send a signal of deterrence against Washington."

China is waiting in the wings.

The Singapore summit, one way or another, is likely to increase its influence.

- Published6 June 2018

- Published30 March 2018

- Published9 March 2018