Greece debt crisis: Eurozone decision down to politics

- Published

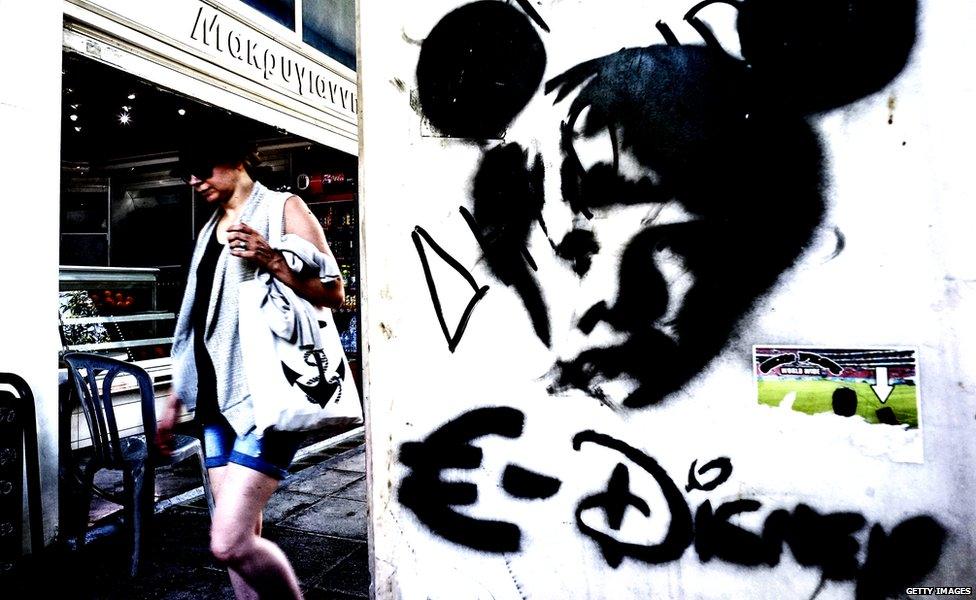

When you look at the numbers Greece's situation can only be described as absolutely dire.

Terminal even.

Banks are running out of money, debts are out of control, and many people have simply stopped paying their bills.

The time to find a solution has all but expired.

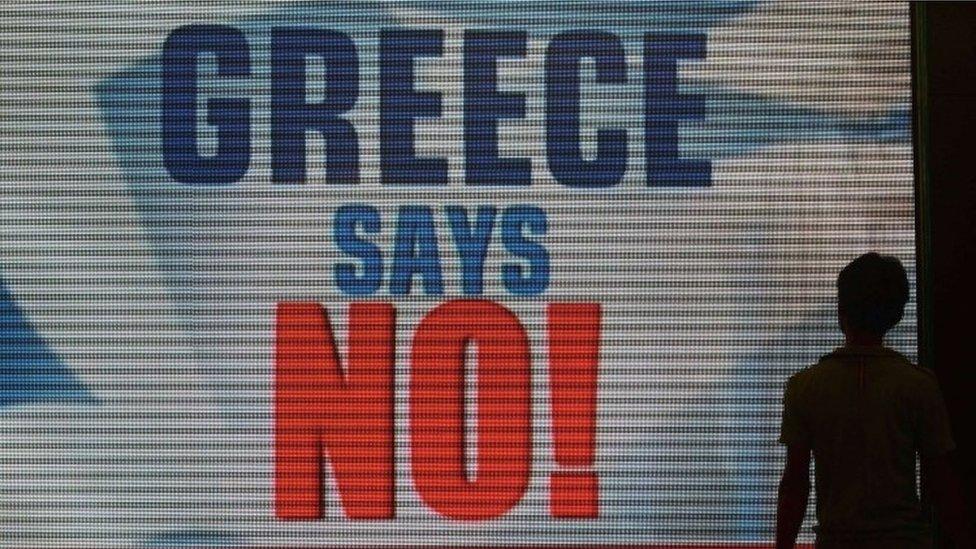

And when you look at the politics, at first glance, things don't appear to be much better.

Six months of angry rhetoric, bluster and frustration since the Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) took office in January.

Even without its combative former finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis ("I shall wear the creditors' loathing with pride"), the government's relationship with many of its eurozone counterparts is characterised by disagreement and distrust.

And fiscal hardliners like Germany and Finland see no reason to cut Greece any more slack.

Calls for Greece's ejection are loud in Germany but France has been more conciliatory

Newer EU member states in Eastern Europe, which went through painful economic transitions themselves when they dispensed with communism, are equally dismissive.

Many of them are poorer than Greece. Why should they pay more to save it again?

And then there are the other bailout countries - Ireland, Portugal and Spain - that have all taken a big hit in the last few years.

All three of them also have centre-right governments defending majorities in upcoming elections.

Give too much to Greece, and their voters might decide that protest voting works.

All of that seems to suggest that any chance of a deal to continue financing Greece, in a way that is acceptable to all sides, is disappearing fast.

And yet, and yet…

The EU (and the eurozone) often makes its biggest decisions in times of crisis at the 11th hour.

The European Commission, which is supposed to act as the guardian of the common good, will continue exploring every avenue.

And a group of countries led by France seems determined to keep the show on the road one way or another.

French Prime Minister Manuel Valls said this morning that France "cannot take the risk" of Greece leaving the eurozone.

"The basis for a deal does exist," he said.

So President Hollande will push hard to prevent a "rupture".

As usual, much will depend on German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

She knows that plenty of senior figures in her party, her finance ministry and the influential German media have concluded that now is the time to let Greece go.

But she has always been a moderating influence.

And even now she must be asking herself the question - does she want the eurozone to crack, with unpredictable consequences, on her watch?

Capital controls have limited Greeks' access to cash to €60 a day

Is that how she will want to be remembered?

Throughout the eurozone crisis the political drive to keep the single currency secure has often been underestimated.

It is now under pressure as never before. But in the end this will be a political decision.

The fact that US President Barack Obama has become personally involved in the negotiations - with individual eurozone leaders - will have an impact as well.

Of course, there are any number of practical difficulties ahead. Some kind of bridging finance will be needed just to get Greece and its banks through the next few weeks.

Eventually, there will have to be agreement on some kind of debt relief as well, otherwise Greece will continue to sink.

And there is no question that the prospects for a deal have diminished in the past two weeks.

Given the weight of events, it all feels most unlikely.

But never rule it out. Not until the very last moment.

- Published10 July 2015

- Published7 July 2015