Greek debt crisis: Where do other eurozone countries stand?

- Published

Alexis Tsipras will have his work cut out during talks with his eurozone partners

Eurozone leaders are back in Brussels to discuss how to deal with the growing debt crisis in Greece.

Greek voters overwhelmingly rejected the terms of an international bailout on Sunday.

Although some countries are keen to strike a compromise, others have taken a more hardened stance.

BBC News takes a look at where each nation stands.

The key players

Germany

Mrs Merkel is under pressure at home to kick Greece out of the eurozone

The calls for Greece's ejection from the eurozone are loudest in Germany.

Greece's fate in the eurozone will have big repercussions for Chancellor Angela Merkel, who is coming under domestic pressure to abandon financial support for the Greeks.

Ms Merkel says there is "still no basis for negotiations". Greece is expected to ask for emergency funds from the European Stability Mechanism, the bailout fund to help eurozone countries in difficulty.

Ms Merkel said that without reform in Greece it was "not possible to go where we want to go".

German Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel has said Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has "torn down the last bridges" between Greece and Europe.

France

Greece may have an ally in French President Francois Hollande

France's Socialist government, more of a natural ally to Mr Tsipras' far-left Syriza party, has been more conciliatory.

French President Francois Hollande says he wants Greece to stay in the euro but it needs to "make serious, credible proposals".

"The onus is on Greece to make some proposals. It's up to Europe to show solidarity by giving them a medium-term outlook, with immediate aid.

"We are not going to speak about Greece every three months. Finally we need speed. It's this week that the decisions have to be taken."

Prime Minister Manuel Valls warned on Tuesday that a Greek exit from the eurozone would have global consequences and insisted the basis for a deal still existed.

"There is no taboo subject when it comes to [Greek] debt," he added.

Alain Juppe, a former prime minister bidding to be presidential candidate for the opposition Republicans, wrote, external (in French) on the other hand that Greece's departure from the single currency could be organised "without drama".

Italy

Italy's Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said the deal "can be found"

The Italian government is likely to join France in a push for compromise. Like Greece, Italy has large levels of public debt and is seen as vulnerable to the aftershocks of a Grexit - the prospect of Greece leaving the euro.

Arriving at the summit in Brussels on Tuesday, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said it was in Greece's "strong interest to stay in the euro".

"I believe that they will do everything to reach a deal and I think that not today, but in the coming hours this deal can be found," Mr Renzi said.

But Greece "must follow the rules", he stressed.

"These rules can be interpreted with a bit of flexibility but as all eurozone countries know, they must be followed."

Sandro Gozi, Italy's top EU Affairs official, said both sides were to blame in talks he described as "a dialogue of the deaf".

"If everyone thinks they are totally right and the others are totally wrong we will not make progress," he told Sky Italia.

Bailed-out nations

Spain

Spain's Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy said Greece "must follow Europe's rules"

"Greece forms part of the euro and that's an obvious fact," said the Spanish Economy Minister, Luis de Guindos. "We all want Greece to stay part of the euro."

He said the Spanish government was "open" to new negotiations with Greece.

But Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy said that if Greece was to remain part of the eurozone, it needed to undertake reforms to pay off its debts.

"We're inclined to help Greece but Greece must follow Europe's rules,'' he said.

Spain was also badly hit by the financial crisis and imposed austerity measures to tackle a shrinking economy and soaring unemployment.

The radical-left Podemos party, which like Syriza, campaigns on an anti-austerity platform, has enjoyed a dramatic surge in support recently.

It said the results of the Greek referendum were a victory for democracy.

Cyprus

Unusually among the small club of euro nations to have received a bailout, Cyprus has backed Greek calls for its debt to be restructured.

President Nicos Anastasiades said "what is needed, in my view at this stage is to consider the unsustainability of the Greek debt," according to the Cyprus Mail, external.

Cypriots know better than most the effects of a financial crisis - its biggest banks nearly collapsed in 2013, amid heavy exposure to Greek debt.

Irish PM Enda Kenny, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades and Portugal's Pedro Passos Coelho all say they want to see a solution

Ireland

Prime Minister Enda Kenny, whose own government imposed tough austerity measures on voters following Ireland's bailout, insisted nobody wanted to see Greece leave the euro.

He said Alexis Tsipras was "doing the right thing" by putting fresh proposals to the European institutions, but warned they must make "economic sense".

Media reports on Tuesday, external suggested Ireland may have to contribute up to €1bn (£700m) to a bailout programme for Greece if the country secures financial assistance for a third time.

Portugal

Leaders in Portugal have rejected comparisons with Greece and urged Mr Tsipras to come up with an alternative range of proposals in order to appease fellow eurozone members.

Portugal received €78bn of loans from other eurozone members and the IMF back in 2011, but insists it has made "sacrifices" in order to move forward.

Speaking on national television Deputy Prime Minister Paulo Portas said: "The Portuguese have made a lot of effort to beat bankruptcy and do not deserve to be associated with the Greek situation."

He called on the will of the Greek people to be respected after Sunday's referendum, but urged the government to come up with an alternative, viable proposal "that would be acceptable to all".

Other stakeholders

Slovakia and the Baltic States

Slovakia's Finance Minister Peter Kazimir (C) believes Greece could leave the euro

Governments from Estonia to Slovakia have taken a notably harder line when it comes to negotiations with Greece.

They insist they are too poor to pay for its mistakes and believe it should have stuck to austerity measures laid out in its original bailout deal.

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite criticised the Greek government for arriving at Tuesday's emergency summit with "only picture but not papers".

"The picture we know ourselves, we don't need that anymore," she said.

"Europe can find a solution to any problem but for that you need two partners to talk, to trust and understand each other. That's not yet the case."

Slovakia's Finance Minister Peter Kazimir said the prospect of the country leaving the eurozone seemed "like a realistic scenario", while Estonian Prime Minister Taavi Roivas insisted Greek reforms were now "unavoidable".

Latvian Finance Minister Janis Reirs said the country found itself in a similar position to Greece in 2008, and "reasonable comparisons" could be made.

"We made some austerity measures and we put our fiscal matters in order in a speedy manner," he added. "We reduced the public sector by 30% and this was expressed in wages and reduction of staff.

"These structural reforms helped it (Latvia) to become one of fastest growing economies 2012-13."

Poland

Polish Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz says the 'No' vote is likely to lead to Greece leaving the euro

Poland is not yet a euro member, but must join the single currency as a condition of entering the EU.

"The Greeks said 'No' to [European] aid, so they also said 'No' to the eurozone. This will probably be a new stage towards [Athens] leaving the eurozone," Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz told Polish state media.

The prospect of euro membership is unpopular among Poles, and the government has indicated it will not join until the debt crisis is resolved.

Finland, Netherlands, Austria and Belgium

Netherlands Prime Minister Mark Rutte said he was "very cheerless" about the summit

Fiscal hardliners such as the Netherlands, Austria and Finland have offered Germany their support when dealing with the Greek crisis.

Netherlands Prime Minister Mark Rutte told reporters in Brussels he was "very cheerless" about the summit.

"I'm here to keep up the integrity, the cohesion and the underlying principles of the monetary union," he said.

"It's up to the Greek government to come with the far reaching proposals, if they don't I think it will be over soon."

Finland's Finance Minister Alexander Stubb said, external: "The ball is now in Greece's court."

"Negotiations can only be resumed when the Greek government is willing to co-operate and commit itself to measures to stabilise the country's public economy," he added.

Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel said Greece's eurozone partners "can't do it with a gun to our head or a knife at our throats".

Mr Michel said Mr Tsipras had to "face up to his responsibilities".

"If there are no proposals, he bears a heavy responsibility towards his own people first and the eurozone."

Malta

Malta's PM says the future of the European project is now at stake

It might be the smallest nation in the eurozone, but Malta is already paying a high price for the Greek crisis.

Its lending to Greece is proportionately among the highest in the region, with estimates putting it at between 2-4% of the island's GDP.

Arriving at the emergency summit on Tuesday, Malta's Prime Minister Joseph Muscat said it was likely the talks were "a waste of time".

The fact Greece hadn't shown urgency and failed to put forward a proposal was "getting off on the wrong foot", Mr Muscat said.

Finance Minister Edward Scicluna compared Greece to a patient refusing medicine.

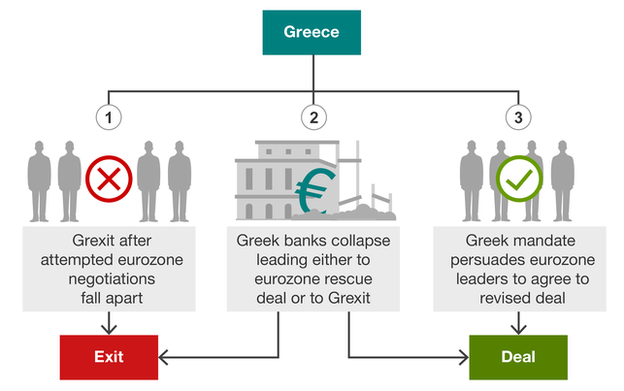

Greek crisis: What are the scenarios?

There are at least three - but at the heart of each of them is what will happen to Greek banks and to the emergency cash funding provided by the European Central Bank (ECB).