Greece debt crisis: Why Tsipras eyes France as last hope

- Published

Many French see Greece as an inherent part of the European ideal

According to Le Figaro, a team of 10 civil servants from the French finance ministry is currently in Athens, helping the Greek government draft its last-ditch proposals to stop a Grexit.

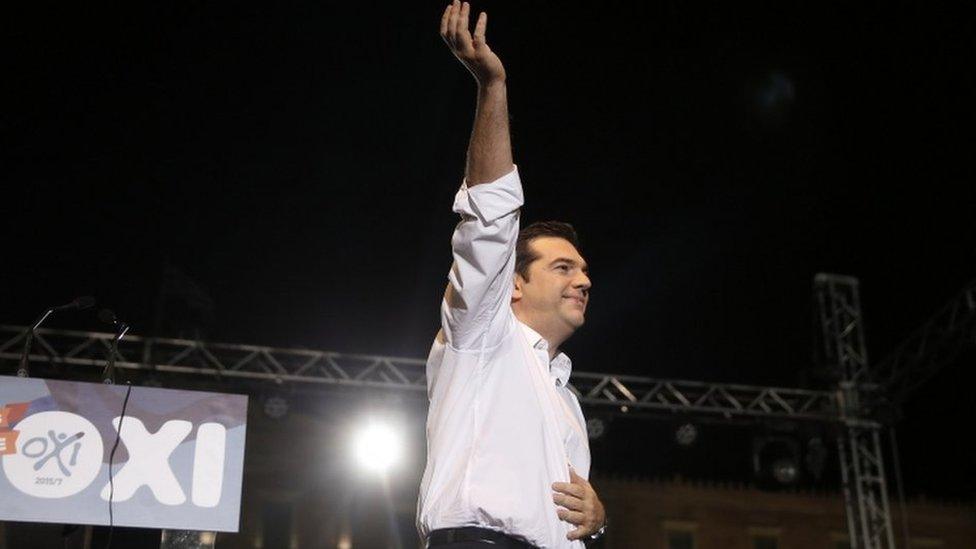

The newspaper also reports, external that on Wednesday morning someone close to Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras rang French journalists in Athens, looking for inside information about what President Francois Hollande plans to do next.

"We are counting on [President Hollande]. France holds the key to the negotiations. Does he understand that?" the Tsipras aide reportedly said.

It should come as no surprise that at this dramatic juncture Greece looks to France as its last remaining hope.

For President Hollande, keeping Greece in the euro is a statement of solidarity

As one by one other EU governments have accepted the likelihood of an impending Greek departure, France cleaves to the imperative of compromise.

On Wednesday, even as Mr Tsipras addressed the European Parliament in Strasbourg, Prime Minister Manuel Valls was telling a debate in the French National Assembly that keeping Greece in the EU was of "utmost geostrategic and geopolitical importance" and that a deal was "within grasp".

Finance Minister Michel Sapin - alone among his peers - broaches the thorny issue of Greek debt. For President Hollande, the watchwords are "responsibility and solidarity" - but solidarity has pride of place.

Why this French penchant for the profligate?

For the political opposition in Paris, the answer is clear. President Hollande indulges the Greeks out of left-wing instinct, and because he knows that France itself is in a parlous financial state.

Thus, when the rest of Europe chants at Greece "Reform! Reform!", France only mouths the words because it feels its own hypocrisy. That, at least, is the charge.

There is something deeper as well, though. A philo-Hellenism beautifully explained, external, as ever, by Le Monde's Europe commentator Arnaud Leparmentier.

For Leparmentier, "Greece sets off ultra-sensitive vibrations in the soul of the West - and especially of France". In other words, the Greece that policy-makers agonise over is not the real country, but an imagined land - "a mirror of France's own illusions."

Part of this is cultural.

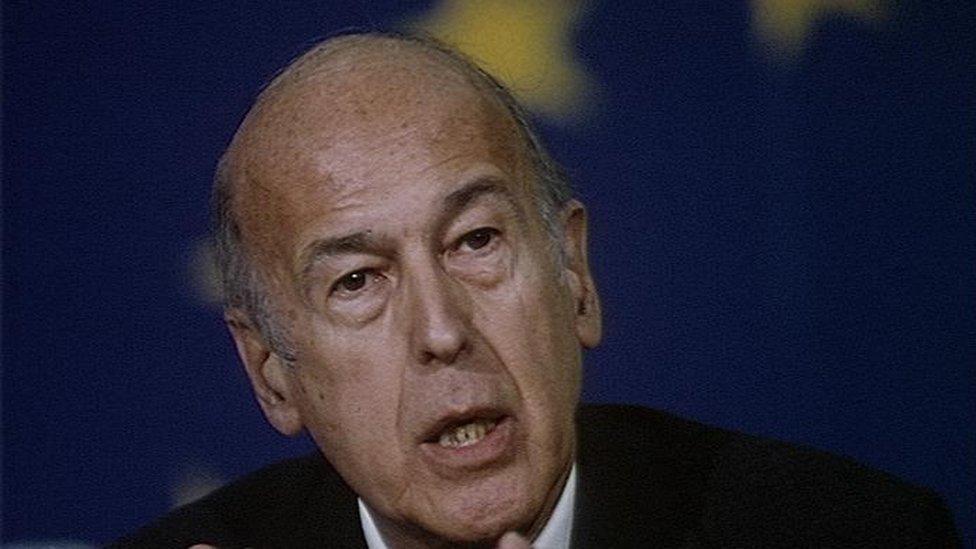

Valery Giscard d'Estaing was initially in favour of Greece joining the EU

When Greece was admitted in 1981, the EU for the first time extended beyond the bounds of old Catholic Europe - the Europe of Charlemagne - to take in the pre-Christian home of reason and democracy.

As President Valery Giscard d'Estaing said at the time: "You do not leave Plato waiting at the door."

But part of it, says Leparmentier, is also political and economic.

Syriza is a Marxist-inspired coalition, and this touches a nerve in a large section of the French establishment.

"Behind the debate over (Greek) debt," he says, "lies the conviction that at bottom property is theft. Or at least that it should be re-distributed… What is happening in Greece raises a question mark over our entire economic order… based as it is on a neutral currency safe from the clutches of politicians."

The truth is that, unlike in Germany or the UK, that basic economic debate has never been entirely settled in France.

Which explains, maybe, why they see Greece differently.

- Published8 July 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published20 July 2015