Train gunman case and migrant influx challenge Schengen

- Published

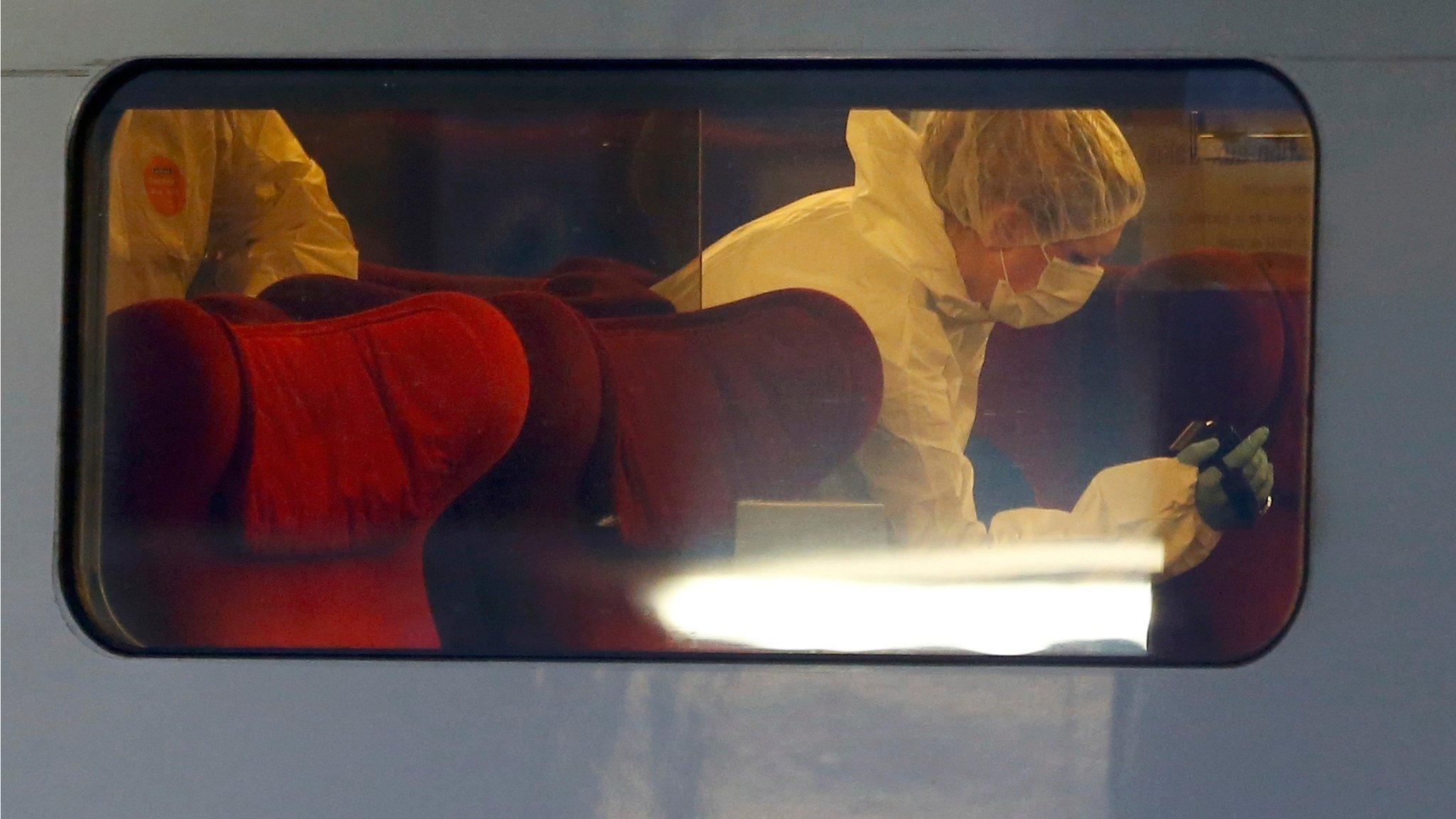

The suspect in the French attack boarded the Amsterdam to Paris Thalys train in Belgium

The Schengen Agreement is the holy grail of European integration and EU officials see it as one of the 28-member bloc's greatest achievements.

But it has been called into question on two fronts, first by Germany's interior minister as his country struggles to deal with the rising number of asylum seekers and now by Belgium in the wake of an attack by a gunman who crossed into France on an international Thalys train.

EU's Schengen Agreement - how it works

EU free movement 'may be in danger', external

Viewpoint: New anti-terror approach needed

Signed in 1985 on the Moselle River on the border between Luxembourg, Germany and France, the Schengen accord has effectively abolished the use of passports on the continent because the 400 million citizens who live in the Schengen area can cross borders without being checked.

Britain and Ireland are not members, but Switzerland, Norway and Iceland are, even though they are not part of the EU.

The Schengen accord has allowed large numbers of migrants to travel across Europe

Recently-joined countries such as Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania have not been allowed entry to the club just yet. International visitors can apply for a Schengen visa that allows them to travel across the whole region.

Schengen has made driving across the continent fairly frictionless (apart from the traffic) and allows millions of Europeans to live in one country and commute to work in another.

But it is has become an important issue in two of the biggest stories in Europe right now: surging migration and the security threat from radical Islamism.

The Schengen system means migrants can arrive on the shores of Greece and Italy and make their way to wealthier countries like Germany, which expects to receive 800,000 new arrivals this year.

German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere: "We support Schengen...but if nobody sticks to the law then Schengen is in danger"

German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere has said the agreement is only sustainable if Europe agrees a permanent mechanism for relocating refugees so that the burden is spread more evenly.

The system also means that potential terrorists can board an international train in one country and travel to another without having their identity confirmed.

In the wake of the events on a high-speed train from Amsterdam to Paris on Friday, when a heavily armed gunman was overpowered by passengers, Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel has called for a meeting of transport ministers to consider whether Schengen should be adapted.

The rules say that ID checks can only be re-introduced in a targeted way based on police intelligence.

Inspecting the details of every passenger on every cross-border train is therefore likely to be against the law, according to officials in Brussels.

More luggage scans at train stations would probably be allowed, but might be rejected for reasons of practicality instead of legality.

Any change to rules on searching rail passengers on international trains would be difficult to introduce

The agreement is loathed by Marine le Pen, leader of France's National Front.

Under pressure from her party during last year's elections for the European Parliament, France's former President Nicolas Sarkozy suggested creating a "Schengen 2" area, made up only of countries which had signed up to a tough common immigration policy.

A member can temporarily put Schengen on hold for 30 days if there is a threat to public safety or if a big event demands it.

Germany did this during the World Cup in 2006 and again during the recent G7 summit in Bavaria.

But there have been no requests this summer, because suspending Schengen would be seen as a direct challenge to the spirit of European togetherness.

- Published24 April 2016

- Published25 August 2015

- Published21 August 2015

- Published3 March 2016