The country where disabled people are beaten and chained

- Published

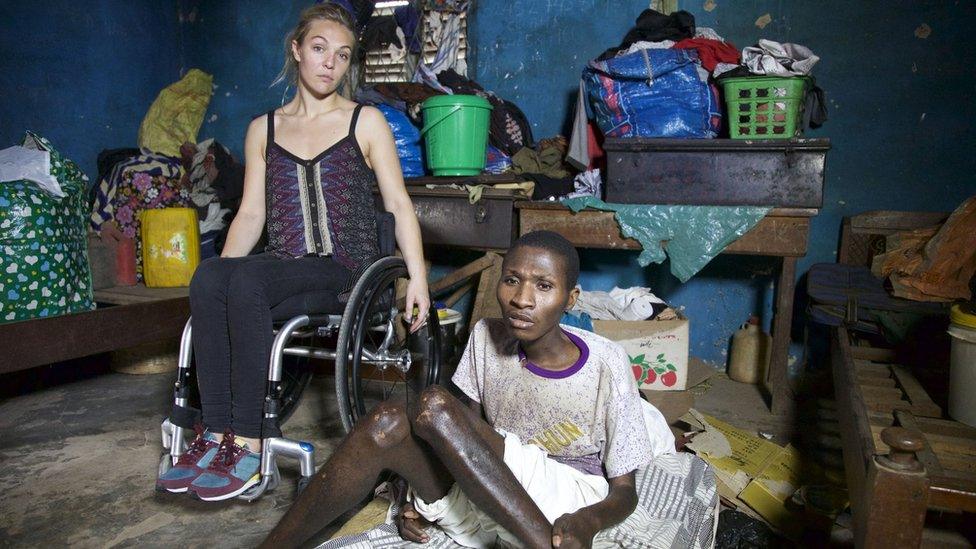

Blessing has been given hope in a centre for disabled people

Presenter and campaigner Sophie Morgan recently visited Ghana to see what life is like for disabled people there. What she found came as a big shock.

When I became paralysed in a car crash at 18, travelling abroad to new countries really helped me adjust to my disability. In the 12 years that have passed, I still find that whenever I am out of my comfort zone I am at my happiest.

Most trips I have taken involved forethought and planning, not just about whether I'd be able to get around in my wheelchair once I got there, but also about local attitudes. Over the years I have learnt that disability can bring out the best and the worst in people all around the world.

So it was with this in mind that last November I went to a country I had never been to before. And the things I saw made me want to never return.

I was travelling to Ghana to make a documentary about what life is like for some of the five million people who (according to Human Rights Watch) have a disability in the country.

To many, Ghana is a beautiful, safe country, the jewel in West Africa's crown. It's home to a wealth of resources that make it a stable and prosperous economy.

But I found some things that many tourists, holidaymakers or backpackers would never see. Nor, in fact, would many Ghanaians.

Some disabled people haven't left the same room for 15 years

The people I met during my trip were mostly devout Christians, but who had imported traditional beliefs to shape the way they explain disability. It soon dawned on me that for many people, disability was considered not a physical or mental impairment, but in fact a spiritual sickness or curse that could either be healed by prayer or by confinement, and in some cases by physical violence.

I found this belief everywhere in the two weeks that I was there.

The first time I witnessed it was, I suppose, a relatively benign example. I was invited to meet a young Ghanaian family in the capital, Accra, to see how they managed life and work. The mother Beatrice and father Alfred are both disabled but, with a four-year-old son to educate, and bills to pay, they work hard to make ends meet.

Beatrice has polio and suffers terribly with low self-esteem having been ostracised almost all of her life. Being both uneducated and wheelchair-dependent, she has few work opportunities, so she sits beside the road every day selling oranges.

After an hour in the boiling sun, it became clear that Beatrice was not running a successful business. People who walked or drove to the area would stop at the other vendors around us to buy fresh fruit, but almost all of them shied away from Beatrice when they saw her wheelchair.

"It's normal," she said quietly. "They think they will catch a disability from me."

The next time I encountered this idea it was far more sinister and was at one of the hundreds of prayer camps found in Ghana.

Grace was given "medicine" at a prayer camp

I tried for a long time to get access to film at one of the mostly Christian prayer camps near Akkra, but was told this wasn't possible. Instead I was able to visit one of the Muslim spiritualist camps in the area.

On arrival, I heard a terrifying screaming sound coming from one of the camp's many wooden and concrete huts. It made me feel intimidated as I moved around the outdoor waiting room filled with disabled men and women sitting patiently, waiting to be healed.

I quickly saw where the noise was coming from as a young girl and her mother fell out of one of the buildings.

The girl, aged around 11, had tears, blood and snot streaming from her eyes and nose. She was screaming relentlessly, and fell feebly to the ground as I watched. Her mother was trying hard to hold her but was sobbing herself.

When I got to them, the child ran at me. I've never seen anyone so scared, her eyes were wild, and full of utter terror. I was told that the woman who runs the camp had put "medicine" in the girl's eyes, nose and ears and all I could understand was that it was because the child had a "curse". I later discovered she had epilepsy.

All around the camp men and women were shackled because they each had a mental or physical disability, and the chains were part of their treatment, along with beating, starvation and worse.

Disorientated and clearly in distress, one was covered in his own faeces and drinking his own urine, one was eating his own faeces, one was masturbating, one was wailing, most were crying and some were just silent.

All of this was justified to me by one person who worked there as treatment to heal the spiritual sickness that causes disability.

I journeyed all over the country to investigate further and found many disable people in difficult situations.

For many of them there is almost no access to equipment, education, transport, healthcare or work. As a result, many live in abject poverty. The stigma attached to disabled people and their families has shocking consequences, including confinement and torture.

There are also unconfirmed reports that sacrifices of disabled children take place, conducted by so-called "fetish priests".

More from the BBC

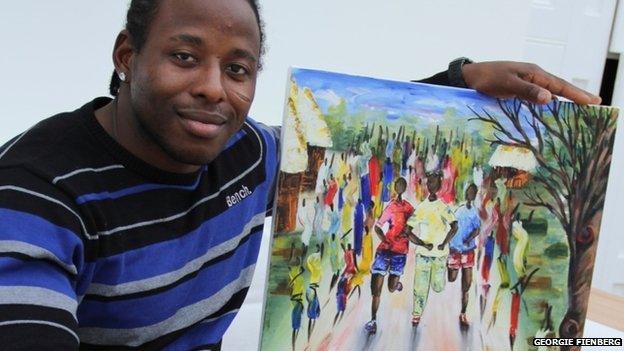

Paul Apowida: From Ghanaian 'spirit boy' to UK soldier

Attempts were made to kill him as a baby because he was labelled a "spirit child" - a youngster possessed by an evil force. So-called spirit children are typically born with physical disabilities or identified as being the cause of misfortune.

The Ghanaian government has been called upon to act on these breaches of human rights, not only by Human Rights Watch, but also by the UN special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, who reported that Ghana's treatment of people with psychosocial disabilities - in particular the practices of shackling the mentally ill to trees, depriving them of food or using electroshock therapy without anaesthesia - may constitute torture.

Mendez's report was given to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva last year, but my journey to Ghana revealed little has been done to address the plight of disabled people.

I asked for an interview with the Ghanaian minister for health but they put forward the secretary of the National Council on Persons with Disabilities instead. He told me that the government had done nothing to stop this treatment so far, that often disabled people are not considered, even when it comes to decisions that affect them.

My time in Ghana has affected me in many ways. In the UK there are difficulties that act as a catalyst for much of the advocacy and campaigning work I do and we, like many other parts of the world, have a long way to go before we can say that being disabled isn't by definition disabling.

When I became disabled I thought my life would be over but, thanks to my friends, family, society and the government, this has not been the case. I have created a new life, one in which I feel deeply fulfilled and happy. But having seen the conditions in which disabled people exist in Ghana, it's impossible not to feel overwhelming guilt mixed with gratitude for my good luck.

Watch Sophie's journey on The World's Worst Place to be Disabled? which airs on Tuesday, 28 July at 21:00 BST on BBC Three as part of the Defying The Label season about disabled people.

Follow @BBCOuch, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external or email ouch@bbc.co.uk