The casualties of this year's viral conspiracy theories

- Published

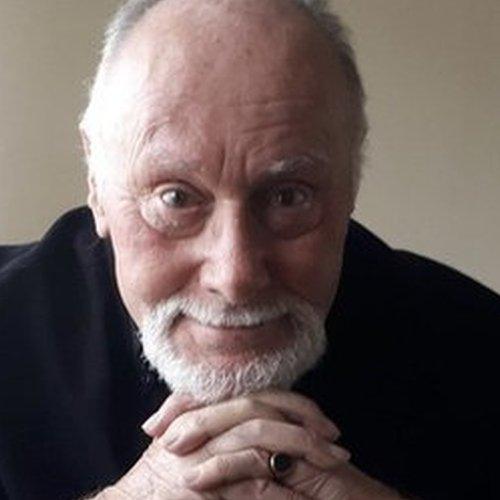

Brian with his wife Erin, who died after contracting Covid-19

Conspiracy theories ripped through the internet this year, destroying relationships and endangering lives.

The flurry of online falsehoods about coronavirus began as soon as the pandemic hit.

Misleading pictures suggesting tanks were rolling down village streets and lists of false diagnostic tips were frantically forwarded on WhatsApp.

As luck would have it, I had just begun my job reporting on the impact of online disinformation.

With the help of a BBC team of experts, I got to work looking into the spread of one really viral post.

A protester's sign casts doubt on Covid-19's existence at a demonstration in California in May

At first glance, the post seemed legitimate, because the information was attributed to a trusted source: a doctor, an institution, or well-educated "uncle". It hopped across Facebook profiles around the world, translated into Italian, Arabic and a dozen other languages.

Votes, viruses, victims: 2020 in disinformation

A special programme from the BBC Trending team.

But along with useful information like "wash your hands", it listed false cures and phony diagnostic tests.

One of the people most responsible for its online spread was an 84-year-old pensioner from Buckinghamshire.

Peter's post went viral

Peter Lee Goodchild assured me that he did not intend to share bad information - but his version of the dodgy post accumulated more than 400,000 shares in early spring.

Have his online habits changed since he went super viral? Not a whole lot.

"Four times I've been pulled up by Full Fact or one of the others who vet Facebook to say 'No that's incorrect' or 'That wasn't said' or 'That didn't happen'," Peter explained when I spoke to him later.

He told me he posts on Facebook now more than ever.

The human cost of misinformation

Peter may have had good intentions, and although some of the information in his viral post was wrong, it wasn't critically dangerous.

That's not always the case when it comes to online falsehoods. Our team found numerous links around the world between misleading and false posts online and serious real world harm.

False claims about 5G technology inspired arsons attacks on phone masts and assaults on telecommunications workers. We catalogued mass poisonings and overdoses of hydroxychloroquine - a drug that world leaders like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro falsely claimed cures or prevents Covid-19.

Brian and Erin both came across conspiracy theories on Facebook

There were riots and poisonings - all because of bad online information.

But Brian's story stood out. He's a 46-year old taxi driver from Florida who I first interviewed in May. Because of posts he had seen on Facebook, he believed a variety of false claims: that coronavirus was not real, not serious, or somehow linked to 5G technology.

He didn't wear a mask or worry too much about social distancing. But then Brian and his wife Erin fell seriously ill with Covid-19 and ended up in hospital.

As his wife remained in a critical condition, he regretted not trusting expert advice.

"We just can't be playing around anymore," he lamented. "This thing is real."

Brian thought the virus was a hoax until he and his wife caught it

In August, Erin died due to heart complications linked to the virus.

I caught up with Brian at the end of what has, understandably, been a difficult year for him. He's now being careful about following health advice - and keeping his online habits in check.

Brian's social media use has changed since his recovery

Conspiracies closer to home

As the year progressed, we watched as the nature of bad information changed.

As we learned more about the virus, the rumours about societal collapse, martial law, and straw-grasping health "tips" mostly disappeared.

What took their place were conspiracy theories - pushed by highly motivated individuals.

Newly-emerged influencers gained huge online followings by promoting baseless claims about the pandemic. That includes denying the virus existed or suggesting the outbreak was planned and managed as some sort of sinister plot.

Their theories were often blatantly inconsistent - for instance, accusing authorities of incompetence in one breath, and in the next alleging they managed legendary logistical feats.

My inbox quickly flooded with pleas for help from people with friends or family members under the spell of these influencers.

The most striking email was from the son of a leader of Britain's conspiracy community.

Sebastian’s mum became one of the leaders of Britain’s conspiracy community

Sebastian Shemirani got in touch because of his fears about his mother's impact on public health - and their relationship.

Sebastian's mum Kate Shemirani has collected tens of thousands of followers with false claims - including denying coronavirus exists, blaming the symptoms of Covid-19 on 5G radio waves and likening the NHS to Nazi Germany. She's spoken to crowds of thousands at protests in London.

"This is her five minutes of fame and when this is over, people will forget about it," Sebastian told me.

"But you know the disaster that goes on within my family and the relationships that she's losing now - that stuff stays forever."

In response to her son's interview at the time, Kate Shemirani told us: "From what I can see it would appear … a "conspiracy theorist" is actually now anyone who believes something other than what your controllers want them to believe. I find this deeply disturbing."

I've spoken to psychologists, experts and even people who used to believe the Earth was flat about how to repair relationships ravaged by cult-like online conspiracies.

"There is no silver bullet, there is no argument you can present to someone… that will change their mind," explains psychologist Jovan Byford.

"The point is to infuse their thinking with counter arguments so the next time they approach a conspiracy theory in a different way."

The vaccine lies ahead

The embers of 2020's blaze of bad viral information are still glowing as we head into 2021.

People around the world are starting to receive coronavirus vaccines - and conspiracy theorists will be focusing on this in the months ahead.

Just as the vaccine roll-out began, I investigated how the feet of a Texas woman named Patricia were used to fuel anti-vaccine propaganda online.

Patricia came down with an unexplained skin condition - but a misunderstanding about what might have caused it set off a chain of events that turned her foot into fodder for anti-vaccine activists.

She joins a long list of casualties of viral conspiracies in 2020.

Do you have a story to tell? Email Marianna, external

Subscribe to the BBC Trending podcast or follow us on Twitter @BBCtrending, external or Facebook, external.