How I talk to the victims of conspiracy theories

- Published

Sebastian's mum is one of the leaders of Britain's conspiracy community. He spoke exclusively to the BBC's specialist disinformation reporter Marianna Spring about the impact that his mother is having on public health - and their relationship.

It was a sunny autumn morning when I opened up my inbox to see a message from someone called Sebastian.

I recognised his distinctive surname immediately. The day before, I had been covering anti-lockdown protests in central London. Sebastian's mum, Kate Shemirani, was one of the headline speakers.

A week later, the weather had turned. Drenched from a torrential downpour, I found myself sitting in a dimly-lit London basement opposite Sebastian.

He's a 21-year-old university student studying philosophy and politics. He seemed nervous - but determined. He told me he felt a duty to speak out, for the sake of public health, and for others whose loved ones may be going down a similar path.

Over the course of three hours he detailed how his mum had gained a huge online following by spreading falsehoods about the pandemic. She's denied that coronavirus exists, alleges that the government is planning a mass genocide, and has compared the National Health Service to Nazi Germany.

Her views - broadcast to tens of thousands of online followers and often repeated by even larger accounts - threaten to undermine critical public health messages. But for Sebastian, it was also an intensely personal story.

Conspiracy theories were his childhood lullabies. Starting from when he was about 10 or 11, he says, he was shown YouTube videos about secret plots and given books about "lizard people".

Sebastian Shemirani hopes to help others whose families have been affected by conspiracy theories

Sebastian got good grades and ended up going to a private boarding school. The time away from his family resulted in him challenging his mum's baseless claims.

He described to me in heartbreaking detail the breakdown of their relationship. He left home when he was 17, and these days the little interaction he has with his mother comes via text message.

"There's no way for me to talk to her at all because she's completely obsessed," he said.

"When this is over … and everything she said is forgotten and the 'global genocide' hasn't happened, people will forget about it," he told me. "But the disaster that goes on within my family… that stuff stays forever."

BBC Trending

In-depth reporting on social media and online culture. Listen to our podcast - from the BBC World Service.

Human cost

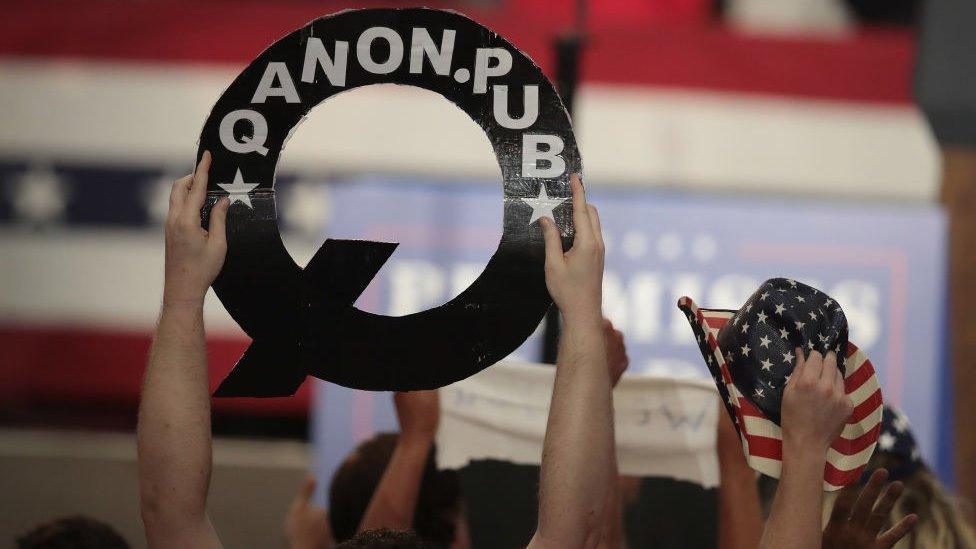

I've spent a lot of time this year covering the human impact of conspiracy theories - from the pro-Trump movement QAnon to the explosion in coronavirus misinformation.

In the summer, I interviewed Brian, a man in Florida who believed false claims that Covid-19 was a "hoax". His precise views shifted around. Sometimes he thought the virus wasn't real - other times he believed that it was totally harmless, or at least no more deadly than the flu.

Throughout the pandemic, he more or less carried on as normal, until both he and his wife caught the disease and ended up in hospital. He survived; she died.

Brian thought the virus was a hoax - until he and his wife caught it

Sebastian's was one of thousands of messages I've received since, from people who fear they are losing loved ones down the rabbit hole of online conspiracy.

Legitimate debate

I always stress that there are legitimate concerns about the effects of lockdown measures on mental health, education and the economy.

Reporting on conspiracy theories is not about clamping down on healthy political discussion. And of course there are valid debates about the still-developing science. There's a lot about this virus that we just don't know.

But the kinds of stories I hear about are something else entirely.

They are tales of sinister plots - supposed plans to implant microchips in the world's population and kill and enslave billions. Or completely unscientific ideas - that the virus somehow "doesn't exist" and that the health authorities are completely wrong.

The pro-Trump QAnon conspiracy theory took off online

How do you talk about conspiracy theories?

Unfortunately, some people are so entranced by these fictions that that they lose their grip on reality. Some take it to extremes. I've been sent abuse, even death threats.

But what about those who are only starting down that path? I've been trying to answer a key question that keeps popping up in my inbox: how do you talk to people who are at risk of buying into dark fantasies?

Sebastian's relationship with his mum has broken down

The experts I've spoken to suggest some answers. First of all, try not to cut the person off. Address the issue as soon as possible - but do it with empathy.

Many of us are feeling very anxious about the pandemic, and conspiracy theories give simple, satisfying answers to a problem that seems overwhelmingly complex.

Psychologists like Jovan Byford from the Open University tell me that a good strategy is to try to get to the bottom of the person's legitimate concerns and to find out how they are feeling.

Depending on how wedded they are to conspiracies, this can be a long process.

"Sit them down and just discuss it for hours until they realise what they're saying is not true," Sebastian suggests. "If you don't nip it in the bud, it will grow and grow."

Another tip is to try to figure out where the person is getting their information. Are they quoting a fringe YouTube video (which may have been fact-checked and debunked), or people in the echo chamber of a conspiracy-minded Facebook group?

Present facts and evidence neutrally, the experts say. Rational questions can provoke reflection, and critical thinking. And always listen to people's deeper concerns.

In the week since we first aired my interview with Sebastian (you can watch it above or listen here), Kate Shemirani's Twitter account has been suspended for violating the site's rules on sharing harmful coronavirus misinformation.

When we put her son's claims to Ms Shemirani, she did not directly respond, but did tell us: "From what I can see it would appear a 'conspiracy theorist' is actually now anyone who believes something other than what your controllers want them to believe... I find this deeply disturbing".

Sebastian's story captured the attention of people across the world. He hopes that other families might be spared the pain that his has suffered.

Marianna Spring is the BBC's specialist disinformation reporter. Her focus is on investigations and features about the human toll of misinformation, online abuse and the social media sphere. Follow her on Twitter @mariannaspring, external

Subscribe to the BBC Trending podcast or follow us on Twitter @BBCtrending, external or Facebook, external.