Q&A: Government Spending Review

- Published

After months of warnings, the UK's "age of austerity" will begin in earnest on 20 October when the government announces the results of its Spending Review.

It will give us the details of which government departments will need to cut their spending, and by how much.

So why are cuts on the cards, what might the impact of those cuts be, and are there any alternatives to cuts?

Why is the government making cuts?

The public finances are in a poor state.

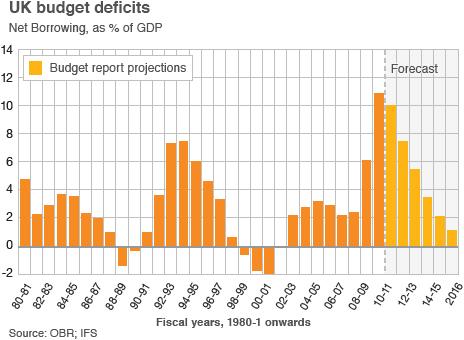

In the 2009-10 financial year, the budget deficit hit a record £155bn, meaning the government spent significantly more than it earned from taxes.

That meant the government had to borrow money to fill the gap, adding to the UK's growing debts. Total debt is expected to reach £900bn (70% of GDP) in the next few years.

Big cuts to spending are therefore planned to reduce the budget deficit and allow the government to start paying back its debts.

Are there any alternatives?

In closing the gap between income and expenditure, the obvious alternative to cutting spending is to raise taxes.

Tax increases are being introduced, but they account for less than a quarter of the £86bn target.

The previous Labour government, responsible for many of the tax increases adopted by the coalition, said it would aim for something closer to 67% cuts and 33% tax rises. Labour's new leader, Ed Miliband, has voiced his support for a 50-50 split.

Labour also favour spreading the cuts over a longer time period in order to reduce the pain.

Some left-leaning think tanks have also proposed alternatives. One - Compass - argues that reforms to the tax system, including introducing a 50% income tax rate at a lower threshold, would reduce the need for cuts.

It adds that the cuts should be selective rather than across the board, with items such as the Trident nuclear submarine programme and Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) in the firing line.

What will the impact of cuts on the economy be?

According to Labour, the economy remains fragile and severe cuts to public spending should wait until the economy is strong enough to withstand them.

They say cuts on the scale being proposed risk propelling the UK back into recession - which would push up unemployment and welfare bills as well as cutting tax receipts, thus hampering efforts to cut the deficit.

Economists, as ever, are divided over the impact cuts could have on the UK's recovery from recession.

The new Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts the economy will grow by just 1.2% this year, and by 2.3% in 2011.

The coalition government has put deficit reduction at the heart of its economic policy, arguing that the poor state of the UK's public finances poses a greater threat to economic recovery than cuts in spending.

The chancellor has also pointed to the Greek debt crisis that erupted in Europe earlier this year as a sign that the UK's debts must be tackled as a matter of urgency. He also says his measures will keep interest rates lower than they would otherwise be, thus helping the economy recover.

How did we get into the current situation?

The UK has been running a budget deficit for many years, financing spending programmes through borrowing.

This is not uncommon, even among the most developed economies, and economists remain divided over the benefits and drawbacks of running a deficit.

But it pushed total government debt up to about 35% of GDP before the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008.

That crisis, and the recession that followed, then forced a huge increase in government spending, with billions spent on stabilising the banking sector, funding economic stimulus measures and welfare costs for the rising number of unemployed.

At the same time the decline in the economy resulted in a fall in tax income, widening the gap between government earnings and government spending to its current record level.

By how much will spending be cut?

The Chancellor, George Osborne, has set himself a target of eliminating the structural current deficit (covering day-to-day rather than investment spending) by 2015-16.

The structural deficit is the part of the deficit that will still exist even when the economy fully recovers from recession.

The Office for Budget Responsibility said at the time of the Budget that the chancellor was on course to achieve that target a year early in 2014-15 with a little bit to spare.

George Osborne says he is "repairing" the deficit to the tune of £113bn by 2014-15. That breaks down into £83bn of spending cuts and £29bn worth of tax rises that year (it adds up to £113bn after rounding).

It is important to note that £73bn of this tightening was inherited from Labour and Mr Osborne has added £40bn. The breakdown for the whole package is now 74% spending cuts, 26% tax rises.

These Treasury figures are expressed in 2014 money (in other words, inflation-adjusted). The spending cuts calculation is based on how much less public spending will be in 2014-15 than it would have been if it had risen in line with inflation.

The independent Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has adjusted these figures and expressed them in "today's money". In other words how would the cuts feel today if a sum equivalent to the same proportion of economic output was removed?

The IFS says on that basis the spending cuts would total £68bn and the tax rises £24bn.

What will be cut?

Although the Spending Review is still under way, the government has already given some clues as to where the axe will fall.

Departments are being asked to demonstrate how they might make savings of between 25% and 40%.

That excludes spending on the National Health Service and on overseas aid, managed by the Department for International Development (DfID), which the government has pledged to protect.

Cuts are likely to be at the lower end of that scale. In his June Budget, external, Mr Osborne said other departments would face budget cuts averaging 25%.

Defence and education spending will not be exempt, but should see less harsh cuts of 10% to 20%, he said.

According to the IFS, that could see unprotected departments such as the Home Office have their budgets cut by 30%.

The welfare system, which accounts for a large proportion of government spending, could also see bigger cuts, adding to the £11bn of savings announced in the Budget.

Is this Spending Review an emergency measure?

No, it's not. The Spending Review is part of the government's normal Budget process, introduced by the then-Chancellor Gordon Brown in 1997.

The review is usually conducted every two years, and allows the government to set the spending limits for every government department for the following three years. Before the reviews were introduced departmental budgets could change every year, making it difficult to plan ahead.