Q&A: Why food prices and fuel costs are going up

- Published

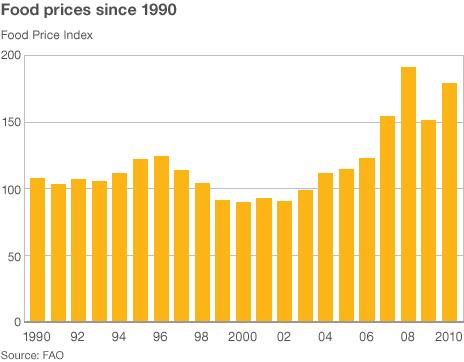

Food prices around the world have been rising sharply and Oxfam has warned that the trend will continue over the next 20 years.

With floods hitting farmland in places such as Australia, which exports its wheat and sugar cane around the world, there are fears that food prices could continue to rise.

In February, the wholesale cost of food hit its highest monthly figure on record, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Food prices remain higher than their peak in 2008, when food crisis prompted riots and demonstrations around the world.

What's more, oil prices have also edged up this year, reaching their highest level in two years.

Why are food prices rising?

Following the 2008 peaks, good harvests for most basic foods helped prices to fall back.

But in 2010, severe weather in some of the world's biggest food exporting countries damaged supplies.

That has helped to push food prices almost 20% higher than a year earlier, according to the FAO. (The 2010 figure was slightly below the annual measure for 2008 as a whole.)

Flooding hit the planting season in Canada, and destroyed crops of wheat and sugar cane in Australia.

In addition, drought and fires devastated harvests of wheat and other grains in Russia and the surrounding region during the summer, prompting Russia to ban exports.

As a result, wheat production is expected to be lower this year than in the last two years, according to US government estimates, although it will still be the third largest on record.

But crucially, production is expected to lag behind the growing demand for food, which is another key factor pushing up prices.

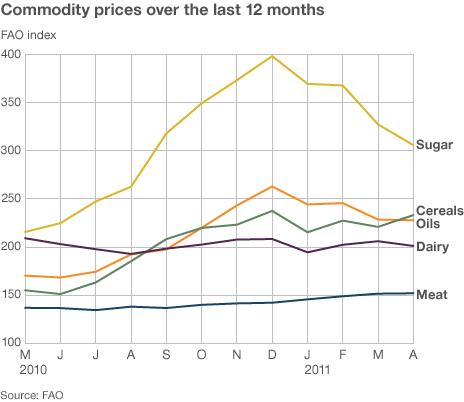

Have the prices of all foods gone up?

The picture is mixed.

Rice, which is a staple in many Asian countries, hasn't risen by as much as other commodities because a record harvest is expected this year.

In addition, some countries that don't rely on supplies from disaster-hit exporters haven't experienced the same price squeeze.

Prices of maize in East Africa, for example, where it is the most important food crop, have fallen by up to 50% following bumper harvests.

There have also been more localised weather problems. They have received less coverage - but are no less important to farmers and consumers in those areas.

Onion prices soared in India earlier in the year, following heavy rains in the west, where much of its supply comes from.

Like many governments around the world, the government has come under severe pressure to act, as onions are such an important part of the Indian diet.

In Central America, lack of rain has damaged bean crops and caused the biggest individual price rises, according to a recent FAO report.

The price of red beans, part of the staple diet in the region, has almost trebled in the past year in El Salvador and Honduras.

What about speculators?

The FAO says speculators who trade commodities on the financial markets are not to blame for the huge rise in prices, but they have made matters worse.

Take sugar for example. Production has failed to keep up with the growing demand coming from developing countries, pushing prices sharply higher.

But the Economist Intelligence Unit also points to the role of speculators, who spotted the situation as an investment opportunity and "helped exaggerate" the price rallies.

The World Development Movement (WDM) is keen to curb this betting on prices.

It wants greater regulation of the buying and selling of futures contracts - which are an agreement to sell a commodity at a certain price at a set time.

These were created to reduce uncertainty as the producer has a guaranteed price and the buyer secures the goods they need. It is effectively a way for both sides to reduce the risk of doing business.

But the WDM and others think that trading these contracts like stocks and shares is pushing food prices even higher to the detriment of the poorest people.

And what's happening to the price of oil?

The price of a barrel of oil topped $125 on the London market in April, the highest level for almost three years, although it has since fallen back towards $115 a barrel.

Sharp rises followed political unrest in oil-producing countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Underlying this uncertainty is the rising demand for oil.

Analysts point in particular to the thirst from China for energy to fuel its factories and power thousands of new cars.

Like food, it is difficult to escape the impact of the rising crude prices.

It not only directly affects the cost of fuel and energy, but also feeds into the prices of other goods by raising the cost of production and transportation.

As many economies around the world struggle to recover from a painful global recession, wages aren't rising to keep pace. So many are really feeling the squeeze.

- Published13 January 2011

- Published13 January 2011

- Published13 January 2011