India prices: No winners as families and farmers suffer

- Published

Pushpa Main says it is difficult to afford the food her family needs to be able to do their physical jobs

For Pushpa Main, getting together a daily meal for her family of five is becoming tougher by the day.

"With prices rising for almost every ingredient of a meal, we are finding it difficult to manage," she says, as she prepares her family's dinner of dal (pulses), roti (wheat bread), rice, vegetables and curd.

But as the price of many of these items has risen steadily over the past two years, her salary has not gone up by the same amount, leaving them worse off.

Pushpa works as a domestic help in a western suburb of Mumbai (Bombay), India's financial capital and one of its most expensive cities to live in.

Due to the economic downturn, most people - even those with much better jobs - have not really seen an increase in salaries.

Her husband, a gardener, recently lost his job. Her two sons are undergraduate students.

India's food inflation rose for the fifth straight week last week to 18.32% - the highest in more than a year.

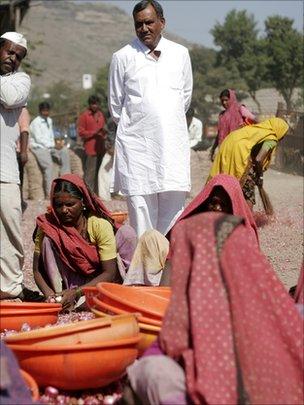

Onion trader Vijay Heda says bad weather has meant only 10% of produce came to market

Onion boycott

For Pushpa, the last straw was the sharp rise in the price of onions a few weeks ago.

A staple for Indian families, used in almost all savoury dishes, its cost has risen dramatically over the past month.

A kilogram which usually costs 20 rupees went up to 85 rupees ($1.87; £1.20). At present, it is 50 to 60 rupees a kilo.

Some residents in north Mumbai have even boycotted using onions in their daily meals.

In response, the government stepped in with measures like a ban on exports and the slashing of import duties.

It also tried importing cheaper onions from Pakistan. However, its neighbour recalled the onion trucks meant for the Indian market from the Wagah border due to its own domestic shortages.

India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh also called a meeting to discuss strategies to tackle the rising food inflation - opposition leaders accuse the government of failing to curb prices.

'Exasperated'

For people like Pushpa, whose monthly income is not more than 6,000 rupees ($133; £84), finding affordable food for her growing family is difficult.

Often, she needs a kilo of vegetables every day, now costing almost 60 rupees.

Balu Kasav lost 80% of his onion crop

In addition, she says they need about 25 kilos of rice and flour per month, so that her husband and children have enough to eat.

Pushpa is exasperated: "We do lots of physical work. My boys are young. We need lots of rice and flour.

"Now I use onions only for grinding spices and don't use it otherwise. Times are so hard!"

'Suffering'

There is the same feeling of frustration at the other end of the chain, among traders and farmers gathering at a major onion market.

Around 100 tractors have assembled for the open auction at Pimpalgaon, approximately 250km (155 miles) from Mumbai.

Farmers here say the unseasonal downpour in November has not only ruined the stocks, but has also damaged saplings for the sowing season.

So while rising prices should mean that producers are benefiting, they claim the damaged crop has resulted in much bigger losses than last year.

"Only 10% of the expected produce has actually come to market," says Vijay Heda, who has been an onion trader for over 30 years. "Everyone has suffered."

He says the sharp increase in prices reminds him of the late 1990s when they shot up, causing the fall of the Delhi state government.

Dharma Devre complains about the huge difference between what farmers earn and customers pay

Balu Kasav, who has a six-acre onion plantation, says 80% of his produce was lost and that he suffered losses of about 300,000 rupees compared with last year.

"Farmers are entirely dependent on nature. There have been times when excessive produce made us sell onions for free a few years back.

"[But] although the prices are high now, due to damaged crops we are not recovering our costs."

He has already borrowed for the new season's sowing. But he worries that even if the next crop does well, he will not make more than 100,000 rupees ($2,215; £1,405) after recovering his losses.

This would would mean he'd make an average of 10,000 rupees per month to support his family of 10 members.

'Disparity'

Dharma Devre, a farmer who has over 20 acres, accepts that no-one can protect them from the vagaries of nature, but is worried about how the next few months will pan out.

"A farmer invests so much in seeds, saplings, fertilisers, labour costs and transport but has no control over prices," he says.

He also complains that both farmers and consumers are currently losing out.

"There is huge disparity between what a farmer gets and what a customer pays. One needs to address these issues."

He suggests money is being made somewhere in between him and customers like Pushpa, in the supply chain which includes traders, wholesalers and retailers.

But traders reject allegations that they have been hoarding stocks to take advantage of rising prices, saying that onions that are produced in this season cannot be stored for more than 10 days and they take four or five days to transport.

'Green revolution'

Traders expect the price of onions to fall in the coming weeks

So can anything be done to prevent food prices soaring?

Economist DK Joshi says that short-term measures such as limiting price rises or exports will not solve the real problem.

"Inefficiencies in the system [supply chain] cause prices to shoot up," he says, adding that "agricultural produce has not kept up with the demand".

Overall consumption is higher due to population increases, and as some people enjoy higher incomes, they demand more higher protein foods such as meat.

Mr Joshi maintains that the real long-term solution is about increasing food supply to meet the demand. "We need something similar to the green revolution now."

In the short-term, traders and farmers say they expect prices of onions to stabilise to between 30 and 35 rupees per kilo in the next two or three months.

But although this will help marginally, without bigger changes, life for Pushpa, who works several hours a day to earn just enough to feed her family, will still be a struggle.

- Published31 May 2011

- Published13 January 2011

- Published13 January 2011