Nature's law: Business will pay the costs of depleting natural resources

- Published

Fishermen are suffering from overfishing and quotas to protect fish

The natural world supports the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people the world over.

It also provides the foundations upon which all the world's major corporate enterprises are built.

For it is not just farmers, fishermen, tour operators and the like that are dependent on nature.

Miners, energy providers, food and clothes retailers - you name it, most companies rely to varying degrees on natural resources.

The majority of businesses, for example, would struggle to survive without clean and accessible water.

The rapid degradation of the natural world by humans, therefore, has a very real and detrimental impact on the ability of people to support themselves and their families, and hits the bottom line of businesses in every sector of the economy.

Fish quotas

Few industries have been hit harder than fishing.

In many areas of the world, fish stocks have fallen by more than 90% since the onset of commercial fishing. Not only does overfishing threaten a vital food source, but it threatens the livelihoods of millions of fishermen.

For some, there simply aren't enough fish left to catch, while for others the quotas and restrictions on time at sea designed to prevent the total collapse of fish stocks are hitting incomes hard.

John Kirkwood has spent his entire working life as a fisherman in the village of Pittenweem, Fife, on the east coast of Scotland.

He left school in 1974 and went straight into a summer job fishing, "and just ended up staying at sea".

Mr Kirkwood is retiring early after seeing his income hit by quotas and restrictions on time at sea

"I bought my first boat for £460,000 in 1986, which was a big gamble for me, and have been a skipper ever since, fishing white fish such as cod and haddock," says Mr Kirkwood.

"We made a good living back then," he says of himself and his six crew. "There were no restrictions and no quotas."

But in the mid-1990s, the European Union began introducing regulations to protect rapidly-dwindling fish stocks.

"The cuts became deeper every year, so we just weren't able to buy enough," Mr Kirkwood says.

"We were better off than many others, but the quotas have put a lot of boats out of business.

"There was a big decommissioning in 2001 and 2003, which cut the Scottish fleet by more than a half."

And nowhere has the impact of quotas and restrictions on days at sea been felt more deeply than on the northern banks of the Firth of Forth.

"There used to be 20 large vessels fishing white fish, but we are the last. When we go, there will be no big boats fishing out of Fife," Mr Kirkwood says.

The Ocean Triumph 11 is the last big fishing boat still in operation in Fife

And it won't be long before they are all gone.

"The income we get now is the same as it was in 1998 - our earnings have stood still for the past 12 years.

"So I am retiring at 53, a good two or three years before I had intended to."

And it's not just overfishing that affects stocks - pollution can have a more sudden and devastating impact on freshwater fish.

For example, river pollution caused by rapidly expanding oil palm plantations and extensive logging in the Kinabatangan floodplain in Malaysia have caused the local fisheries to collapse, with local fishermen losing their major source of income.

Ski resorts

Another sector that has been hit by damage to the natural world - often referred to as biodiversity loss - is tourism.

For example, lions across Africa have disappeared from 80% of their former habitat, hitting game reserves and associated businesses.

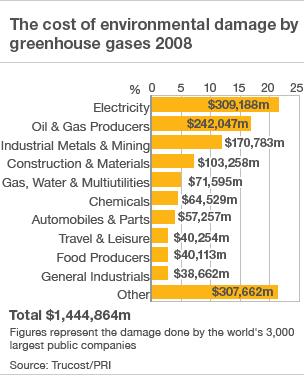

Rising temperatures caused in part by greenhouse gases have also seen glaciers and snow coverage shrinking, hitting winter sports resorts that are seeing ski seasons cut short.

Rising sea temperatures and water levels are also affecting coastal regions and small islands such as the Maldives, and particularly those businesses dependent on coral reefs, 20% of which have disappeared in the past few decades alone.

Disappearing corals

Adrenalin Dive, based in Townsville in Queensland, Australia, is being squeezed on many sides.

Paul Crocombe set up the business in 1987, running trips for tourists to the Great Barrier Reef.

Dive operator Paul Crocombe needs to buy a new boat to visit pristine corals further from the coast

"We used to visit Keepher Reef, 38 nautical miles from Townsville, but this has been severely impacted by coral bleaching and by Crown-of-thorns starfish that eat up the reefs," Mr Crocombe explains.

"This has affected a lot of reefs - Flinders Reef was exceptional but now suffers severely from bleaching due to the higher water temperatures.

"At first the corals get brighter and more colourful as they give off algae, but once all the algae is gone, the corals go white and then die."

The problem is compounded by the Crown-of-thorns starfish, which tend to prey on stressed reefs.

"Now we have to go to Wheeler Reef, which is about as quarter as far again, which adds travel time and fuel costs," Mr Crocombe says.

This, he estimates, requires an extra 30,000 litres of fuel a year, costing the business 42,000 Australian dollars ($41,000; £26,000).

Dive operators have been hit by the destruction of coral reefs

The extra time taken on the trip also puts some potential customers off.

"People say they don't want to go that far so we need a faster, more modern boat to keep the time, and our fuel costs, down.

"If we don't change boats, then our business becomes marginal," explains Mr Crocombe.

He already employs fewer full-time staff, and is now relying on the banks to provide funds for the new craft.

"We are chasing finance now but a new boat costs A$3m, while a second-hand boat costs A$1.2m.

"I think that eventually we will get it, somehow."

Water costs

But it is not just small businesses that are hit directly by biodiversity loss.

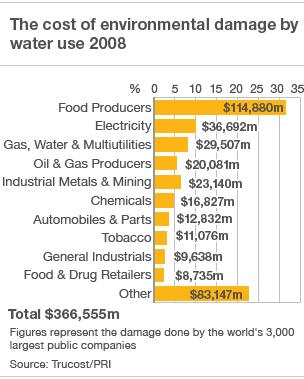

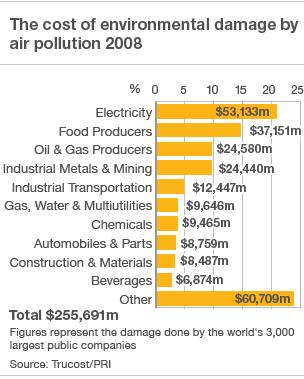

A recent study by the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), conducted with corporate environmental research group Trucost, estimated the cost of environmental damage caused by the world's largest 3,000 companies in 2008 at $2.15tn, the equivalent of one-third of their combined profits.

Increasingly these costs - what economists call externalities - will become internalised.

Consumer products giant Unilever, for example, has been forced to take action to secure the water supply to its tea plantations in Kenya's Rift Valley.

"The local population has chopped down large sections of the Mau Forest, which directly impacts on our ability to catch water," explains Gavin Neath, Unilever's senior vice president of sustainability.

To compensate, the company has spent about £300,000 over the past 10 years on planting more than one million indigenous trees in the forest. It has also spent a similar sum on safeguarding forestry and biodiversity in Tanzania.

Changing rain patterns in California, Spain and Greece are also raising issues over tomato production, just another one of the "serious issues" that could hit the company in the next 10 years, Mr Neath says.

Europe's largest carmaker Volkswagen has also committed to investing $430,000 (£270,000) in re-planting forests and digging rain water pits to secure the water supply to its factory in the Mexican town of Puebla, while brewer SABMiller has paid farmers in Bogota, Colombia, $150,000 to replant trees for the same reason.

The world's largest steel producer, ArcelorMittal, has invested almost $2.1m since 2006 on protecting what is, after iron and coal, the most important component in making steel, by restoring the ecosystems surrounding the Great Lakes in North America that supply water to nine facilities.

Coffee giant Starbucks has also committed millions of dollars to protect the water supply and to ensure natural shade cover to its coffee plantations in Mexico and Indonesia.

Rising costs

More and more major corporations are waking up to the fact that they have to pay to protect or replace the earth's natural resources and services that have, until now, been seen as free.

Many will be forced to do so by increased regulation, just like fishing quotas and pollution taxes, such as carbon credits, that already exist.

And these costs are not peripheral.

According to Trucost and PRI, environmental costs amounted to more than half the combined earnings of about 2,500 major listed companies in developed and emerging markets across the world in 2008.

And as resources come under greater pressure, as they inevitably will, so the bill will continue to rise.

Big business will be forced to adapt, but many smaller businesses and individuals will not have that luxury.

This is the second in a series of three articles on the economic cost of human activity on the natural world.

The first looks at the full impact of the degradation of the natural world on the global economy - both on business and consumers. The third looks at what can be done to slow biodiversity loss, and what opportunities it presents.