Nature's gift: The economic benefits of preserving the natural world

- Published

Forests and the insects that live in them provide huge economic benefits

Slowing down the destruction of the Earth's natural resources is essential if the global economy, and the businesses that drive it, are to prosper long term.

The current rate of destruction is estimated to cost the world trillions of dollars every year, and the damage will only get get worse unless wide-ranging measures are taken to stop it.

The reason is simple - population growth is the main driver behind those factors that are causing biodiversity loss.

There are currently about 6.7 billion people living on Earth, and this number is projected to grow to 9.2 billion by 2050 - that's roughly the population of the UK being added to the planet every year.

This means we'll need 70% more food, according to the United Nations (UN), just one of the many additional pressures on Earth's finite resources.

If left unchecked, these pressures will lead to the ever-faster destruction of nature, which could cost the world $28.6tn (£18.2tn), or 18% of global economic output, by 2050, according to the UN-backed Principles of Responsible Investment and corporate environmental research group Trucost.

That's about twice the current output of the US, the world's biggest economy.

Valuing nature

So what can be done?

A vital step has already been taken - for the first time in history, we now have at least a rough idea of the economic cost of depleting the earth's natural resources.

The economic value of mangroves is often greater than the shrimp farms that replace them

This not only means that governments, businesses and consumers can understand the gravity of the problem, but it also means the value of nature can be factored into business decisions.

As Will Evison, environmental economist at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), says: "No-one is saying we should just stop converting pristine land, just that the value of the environment is recognised".

For example, a study on the conversion of mangroves to commercial shrimp farms in southern Thailand estimated the net economic returns at $1,122 per hectare a year.

The conclusion, at least for the shrimp farmer, is clear - there is an economic benefit of converting the mangroves.

But once the wider costs of the conversion - what economists call externalities - are taken into account, a very different conclusion is reached.

The economic benefits from the mangroves of collecting wood, providing nurseries for offshore fisheries and protection against storms total $10,821 a hectare, far outweighing the benefits of converting them into a shrimp farm.

Damage limitation

There are a number of initiatives, some already introduced and some in the pipeline, that are specifically designed to ensure that the economic value of nature is recognised.

One example is reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, or REDD, under which forest owners are paid not to cut down trees. A number of governments across the world have committed hundreds of millions of dollars to these projects.

Another is habitat banking, the market for which currently stands at around $3bn in the US, where companies that degrade natural areas are forced to restore nature elsewhere.

Trade in forest conservation obligations in Brazil and ground-water salinity credits in Australia have also proved successful.

Alongside these schemes and those like them, there are various compensation arrangements that make those causing environmental damage pay for it, just like carbon credits that currently exist.

Exemptions from these various taxes, charges and fees, as well as subsidies, are also used to encourage environmentally responsible behaviour.

There is also growing pressure for companies to begin incorporating the costs of the damage that they do to the Earth's natural resources into their profit and loss accounts.

Governments have committed hundreds of millions of dollars to preserving rainforests

Only by incorporating these costs into their accounts, many argue, will companies be forced to reduce their impact on the natural world.

"Directors' bonuses don't have to be included [in company accounts] from a pure profit and loss point of view, but they are. Environmental externalities should be the same," says Pavan Sukhdev, a career banker and team leader of the United Nations' The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (Teeb) study.

"This is not a straightforward process and needs standard methodologies accepted by everyone, but it could be achieved within 10 years."

The next step would be to incorporate environmental assets into national accounts.

Protecting assets

But many companies already do acknowledge the costs of biodiversity loss.

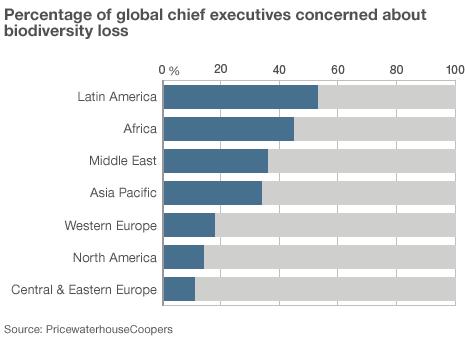

A survey conducted by PwC earlier this year found that 27% of chief executives were either "extremely" or "somewhat" concerned about biodiversity loss, although there was a large disparity between those operating in developed economies and those in emerging markets.

Indeed many multinational companies have made significant investments in protecting the natural resources upon which their success depends.

These include investments to mitigate the impact of tighter regulation, such as shipping giant Swire's decision to buy up swathes of rainforest to offset the possible introduction of pollution taxes in the shipping industry.

Indeed those companies that are well prepared for more stringent regulation, and have made the necessary investment in protecting the natural assets that serve them, will gain an important competitive advantage.

But it's not just a question of risk mitigation - there are also opportunities for companies that act in an environmentally responsible manner.

Brewing giant SABMiller has made considerable investments in reforestation in Columbia and South Africa, as well as setting stringent targets for reducing water consumption - commitments, it says, that helped the company secure licences to brew in Australia, "because the authorities trust that we will be water efficient", says Andy Wales, the brewer's global head of sustainable development.

Contrast this with mining group Vedanta, which has been denied permission both to expand its aluminium operations and to mine bauxite in India after campaigners claimed the company had ignored the needs of indigenous peoples.

Consumer attitudes

Companies also recognise that they need to react to increasing customer awareness of environmental issues.

For example, another survey conducted by PwC in May found that more than half of UK consumers were willing to pay between 10% and 25% more for goods up to £100 to account for their impact on the natural world.

More companies are investing in sustainable practices to meet consumer demand

Such changing consumer attitudes mean that more and more companies are investing in reducing their impact on nature.

For example, the world's biggest retailer Walmart has introduced sustainability criteria as part of its official product sourcing process.

Coffee giant Starbucks has also invested millions of dollars in protecting natural resources because "we know maintaining biodiversity makes a difference to our coffee drinkers" according to Tim McCoy, the company's head of communications.

Natura, the Brazilian cosmetics group with a turnover of $2.4bn, has committed to sourcing products sustainably from natural sources in order to appeal to consumers, while French energy group GDF Suez has invested in conserving biodiversity on its landfill sites purely as part of its "reputational risk management".

Google Maps has even launched a service that allows users to track changes in forest cover across the world.

'Empty rhetoric'

Not everything some companies say about their environmental commitments can be believed, but the fact that they are saying it at all is what's important, says Mr Sukhdev.

"Once you get away from denial, you pass through a phase of understanding and then one of empty rhetoric before you arrive at action. The stage of empty rhetoric is part of the process."

And those companies that do take action will win out in the long run.

The costs of failing to protect the Earth's natural resources and the services they provide, and the price of failing to grasp the opportunities that investing in nature present, are simply too great for those that do not.

This is the third in a series of three articles on the economic cost of human activity on the natural world.

The first looks at the full impact of the degradation of the natural world on the global economy - both on business and consumers.

The second looks at the direct costs to businesses, both large and small.