Africa hails new meningitis vaccine

- Published

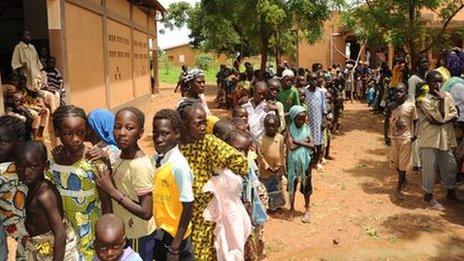

The chance to get a meningitis vaccine that has passed WHO quality checks was too good to miss for thousands of African people

For the people in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, a new meningitis vaccine offers hope of an escape from one of the world's deadliest, most disabling and infectious diseases.

So there is little wonder that the queues were enormous when a pilot project for the MenAfriVac vaccine got underway in the three West African countries in recent weeks.

Unlike most of the alternatives, this vaccine was created specifically for Africa.

This is unusual, as vaccines tend to be created for and marketed in far larger, more lucrative regions, although they may be sold in Africa too.

Moreover, this vaccine was not created by by one of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies.

Instead, it was created by a consortium of scientists and academics, all linked to a non-governmental organization called Path, in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO).

Combined processes

MenAfriVac was created by combining processes from different players in the industry, the entire plan was masterminded from a French town called Ferney-Voltaire.

One process came from a Dutch biotech company, Synco Bio Partners, another from US government research laboratories, called the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

Trials were carried out at clinical trial sites from Ghana to Senegal, and an Indian vaccine maker, called Serum Institute, is manufacturing MenAfriVac.

In short, it has been a bit like assembling pieces of a puzzle, according to Dr Marc LaForce, who has been in charge of the consortium, called the Meningitis Vaccine Project, since 2001.

Lucrative vaccine

Vaccinating children could save millions of lives

The vaccine has now passed the WHO's stringent global vaccine quality checks and is at the final safety-check stage in West Africa.

It has been welcomed by non-governmental organisations such as Medecins Sans Frontieres, which plans to buy several million doses for the region.

There has been a huge demand for meningitis vaccines to combat outbreaks all over the world, from the US to Europe.

That is why the market is so lucrative.

Sanofi Pasteur made around €445m ($620m; £391m) last year from just one meningitis vaccine.

Halting epidemics

But nowhere is the problem as serious as it is in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Here, huge epidemics have swept across a band of countries from West to East Africa, now called the meningitis belt.

Last year, more than 88,000 people contracted it in the region last year. Most of them are less than 30 years old, with the majority younger than 15 years of age.

Dr Samba Sow, who is working on Mali's pilot meningitis vaccine campaign for the ministry of health, hopes a solution may have been found.

"We expect a lot from this vaccine," he says.

"The expected impact is that the big epidemics will hopefully be stopped in this part of Sub-Saharan Africa."

Cheaper processes

Meningitis spreads easily among Africa's poor

The main reason for the rather unusual approach to vaccine development is that existing effective vaccines are too expensive, at well over $50 a dose, according to some estimates.

The meningitis belt is made up of some of the world's poorest countries and many cannot afford more than a tenth of that - 50 cents - per dose, even with a subsidy from charities, according to the Meningitis Vaccine Project.

Take Niger. It is one of the worst-hit epidemic countries, yet each year the country spends just $9 per citizen on health services.

It was this need to keep costs low that resulted in the vaccine being built using this novel modular approach.

This, and Dr LaForce's discovering research that suggested vaccines could be created much more cheaply, at total costs of less than 20c per dose.

'Another approach'

Dr LaForce initially contacted large, established pharmaceutical companies to get them to help create such a vaccine, but failed to win them over.

"There wasn't very much interest in talking about the amounts we were talking about," he says.

"So we started to consider another approach"

So the Meningitis Vaccine Project embarked on a search for companies specialising in the individual technological processes required to make the vaccine.

It negotiated intellectual property deals to make use of the processes and found a developing world manufacturer that was already creating less expensive vaccines, and would thus be able to absorb the know-how and meet global manufacturing standards.

In the end, the Meningitis Vaccine Project came up with a vaccine that costs just over 40 cents to produce.

Market considerations

The modular approach was considered highly controversial to begin with, according to Dr Suresh Jadhav, executive director of Serum Institute

"There were many people who were sceptical about this project," he says.

"That technologies [could come from different] places and manufacturing happen at another place; this was something unheard of."

Now that it has been proven to work, similar methods could be used to create other vaccines, such as one against typhoid, according to the Meningitis Vaccine Project.

Indeed, there is a huge global push to use different mechanisms to develop a wide variety of vaccines that are better aimed at developing countries.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which funded the Meningitis Vaccine Project at launch, earlier this year pledged $10bn over a decade to do just that.

But one pharmaceutical manufacturer says the continent could have had an effective meningitis vaccine much sooner.

In the past, companies have shied away from paying to develop such a vaccine because the market has not been deemed sufficiently attractive, acknowledges Dr Rino Rappuoli, head of research for Novartis Vaccines.

These days, large pharmaceutical firms are combining meningitis strains into a single vaccine that will work in different parts of the world.

But in the past, Dr Rappuoli saw a vaccine he had helped develop, aimed at preventing the spread of a strain of meningitis that exists in Africa, being shelved.

Sustainable funding

In spite of this, Dr Rappuoli is not convinced the Meningitis Vaccine Project's decision to use a modular approach is the right one.

"Yes, maybe you will have a less expensive vaccine," he says.

"Don't get me wrong, I am very happy the vaccine is available.

"But you are not considering the real cost; all the people who die during the years while you developed it."

A better solution would have been for the global health community to have taken on well established, slightly more expensive technology to develop a vaccine for Africa, he believes.

Now, with the vaccine on the market, such concerns are purely academic for the people who live in the 21 African countries that form the "meningitis belt".

To them, the biggest obstacle remains a shortage of funds, which means only three countries will see nationwide immunisation campaigns take place in the near future.

At this stage, the Medecins Sans Frontieres insists, what is required to stop epidemics is sustainable funding.