Brazil reduces poverty but industry feels the strain

- Published

Brazilian retailers are good at drumming up business

It is a paradox haunting Brazil's economic-policy makers - ordinary people have never had it so good, but the country's industry is facing its toughest times yet.

Evidence of the success of Brazil's anti-poverty programmes is fighting for space in the local headlines with dire warnings from manufacturers about the currency's remorseless rise.

And while consumers have more disposable income, domestic production of the goods they want to buy is lagging behind, boosting imports instead.

The International Monetary Fund says the Brazilian economy expanded by 7.5% last year, with growth of 4.5% expected in 2011. But there is concern the economy could need rebalancing.

"Brazilian growth is still being driven by consumer spending and manufacturers are being squeezed by the strength of the real," says Capital Economics senior emerging markets economist Neil Shearing.

So why are Brazilians willing to spend at a time when much of the world is still in tentative recovery mode after the global recession?

Greater equality

The country's consumer boom is partly the result of long-term economic policies now bearing fruit.

Since the start of the Real Plan in 1994, which ushered in Brazil's current currency and ended years of hyperinflation, successive governments have presided over programmes designed to improve the incomes of poorer members of society.

Shopping malls are popular in Brazil

And according to newly published research by the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) think tank, poverty levels have fallen by 67.3% across the country in those 17 years.

The poor, as defined by the FGV, are those living on less than 151 reais (£56.95; $93.50) a month.

Both absolute and relative poverty have declined in recent years, especially in the past decade, during which the poorest 50% saw their incomes go up by 68%, while the richest 10% received a 10% increase.

That means large sections of the population once too poor to have any disposable income have joined the consumer society.

As a result, Brazil is more equal than it has ever been, although by international standards, there are still huge disparities of wealth.

The country's Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, peaked at 0.61 in 1990 - but last year's figure was a historic low of 0.53.

During the same period, Brazil's fellow Bric countries - Russia, India and China - have all seen their levels of inequality increase.

Poverty persists

Building on the success of former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva's Bolsa Familia programme, which raised living standards for millions of people, his successor, Dilma Rousseff, is launching another welfare scheme, Brasil Sem Miseria (Brazil Without Misery).

This is targeted at people in extreme poverty, which is defined as living on 70 reais or less a month.

Dilma Rousseff is intensifying Brazil's anti-poverty drive

According to last year's national census, 8.5% of the population, a total of 16.3 million people, are in this sorry state. Astonishingly, 4.8 million of them have no income at all.

Three-quarters of the very poorest live in the under-developed north and north east of the country, and nearly half of them live in rural areas. In fact, a quarter of all people living outside Brazil's cities are in extreme poverty.

This is "the hard core of poverty", as the FGV's Marcelo Neri puts it. "That's where eradication measures will encounter more difficulties," he says.

Details of the programme remain sketchy, but the government has said it will involve welfare benefits, as well as improving access to public services for the poor and taking steps to integrate them into the productive economy.

Soaraway Selic

But all that government spending on welfare programmes is helping to pump up the economy and drive inflation higher.

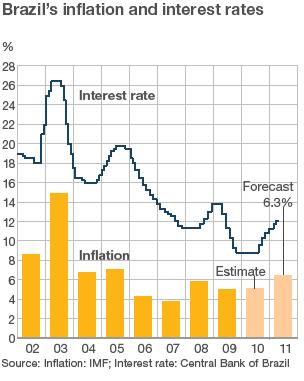

Coupled with soaring food and fuel prices, the effect has been to push Brazil's year-on-year inflation rate to about 6% - far less than in the years of hyperinflation, but worryingly close to the 6.5% ceiling the government has set for 2011.

As long as prices continue to rise at that kind of pace, Brazilian interest rates will remain high.

Although Ms Rousseff was determined to cut the cost of borrowing when she took office at the start of the year, it has already gone up three times since then.

The key Selic rate now stands at 12% - the highest in the G20 group of nations - with analysts expecting a further rise when central bank policy makers meet again on 8 June.

Since interest rates in most developed nations are currently at historic lows, that means Brazil is attracting huge foreign capital inflows from investors seeking a better return on their money.

That, in turn, is boosting the value of the real to levels that are inflicting serious pain on Brazilian industry.

Trade troubles

The strong currency is pricing the country's exporters out of foreign markets and encouraging a flood of cheap Chinese imports, particularly shoes and textiles - good for consumers, but bad for manufacturers.

No wonder Mr Shearing is highlighting "concerns about the two-speed nature of Brazilian growth".

High fuel prices have been adding to Brazil's inflation

Brazil has kept its current account healthy so far by exporting vast quantities of iron ore and soya beans to China, boosted by high commodity prices.

The extent of Brazil's dependence on such exports can be seen in the way the latest falls in world commodity prices have caused the country's stock market to weaken.

"While the commodity-related improvement in Brazil's terms of trade, coupled with rapid capital inflows and comparatively loose fiscal policy, are supporting consumer demand, manufacturers are lagging behind," says Mr Shearing.

"This is best illustrated by the fact that the boom in consumer spending has not been accompanied by a similar boom in the domestic production of consumer goods."

Hot money

In the latest sign of the struggle faced by Brazilian exporters, the local chief executive of electronics giant Siemens, Adilson Antonio Primo, has warned of a "risk of deindustrialisation" in Brazil unless the strong real is curbed.

Mr Primo told the Financial Times it would be "a real disaster" if the currency strengthened beyond 1.50 to the dollar.

Four years ago, Siemens exported 20% of all the goods it made in Brazil. That proportion has since fallen to 12% as the exchange rate has eroded competitiveness.

Mr Primo and others are calling on the government to take measures to stop the flow of hot money into Brazil and reduce the upward pressure on the real.

One idea would be to lock in foreign money by imposing fines on people who withdrew their funds from the country too soon, discouraging speculators who were seeking short-term gains from the high interest rate.

However, the government is afraid of alienating foreign investors in the run-up to the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, which Brazil is hosting. It looks as though Brazil's industry will be suffering for some time yet.

- Published19 March 2011

- Published9 February 2011

- Published10 January 2011

- Published27 October 2010