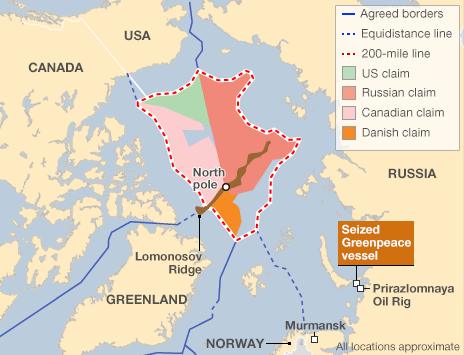

Arctic oil exploration: Potential riches and problems

- Published

Oil firms are keen to exploit Arctic oil reserves

With a seemingly insatiable demand for oil and gas, the world constantly needs to find new supplies.

With current oil reserves coping with increased pressure from emerging markets in China and India, the Arctic and its seas are seen as being of crucial importance.

US oil giant Exxon Mobil, which this week signed a multi-billion dollar deal with Rosneft to explore the Russian Arctic, described the area as "among the most promising and least explored regions for oil".

Experts have known the region is rich in oil and gas reserves, but it didn't realise how much potential until 2009.

In new findings that year, the US Geological Survey estimated the Arctic may be home to 30% of the planet's undiscovered natural gas reserves and 13% of its undiscovered oil.

Huge reserves

It showed that up to 160 billion barrels of oil could lay undiscovered beneath the Arctic - compared to 90 billion barrels previously estimated in the region.

Researchers say that deep ocean basins have relatively low petroleum potential, but crucially the Arctic is one of the world's largest remaining areas where oil and gas are accessible.

Green campaigners fear for the Arctic wildlife

Most of the reserves are projected to be in less than 500 metres of water - roughly a third of a mile deep.

The US government estimates that the world uses around 30 billion barrels of oil in a year.

The figures speak for themselves, explaining why the world's biggest oil firms are clamouring for a piece of the Arctic action.

But the environmental impact of any widespread drilling in the region is a key worry for green campaigners.

Access to the region in the event of any oil spill would be severely compromised, especially in the winter months where only 20% of the region can be accessed by boat.

Cairn Energy, based in Edinburgh, is spending $1bn drilling for oil in the Arctic this year, but faced 12 hours of disruption after Greenpeace attached itself to its oil drilling rig in June.

Clean-up 'impossible'

The group has been lobbying for all oil drilling and exploration in the Arctic to stop.

"All the information we have is that an Arctic oil spill would be impossible to clean up," said Greenpeace spokesman Ben Stewart.

"Rising temperatures mean the ice caps are becoming more accessible for oil firms; there is a bitter irony that the ice melting is being seen as a business opportunity rather than a grave warning."

Other issues include the lack of a deepwater port to remove large quantities of any oil extracted - the nearest facility is nearly 1,000 miles away.

Drilling for oil in some areas of the Arctic could cause toxins such as arsenic, mercury and lead to be released into ocean waters, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

It wants uniform rules for all countries seeking oil or permitting a third party searching for oil within their own territorial waters.

The World Wildlife Fund also has grave concerns about any pollution - and how it can be cleaned up.

According to its Oil Spill Response Challenges in Arctic Waters report , Arctic conditions can impact on both the probability that a spill will occur from oil and gas operations and the consequences of such a spill.

The same conditions that contribute to oil spill risks (including lack of natural light, extreme cold, moving ice floes, high wind and low visibility) can also make spill response operations extremely difficult or totally ineffective.

However, these issues have not deterred major companies from getting in on the action.

This week, US oil major Exxon Mobil signed an Arctic oil exploration deal with Russian state-owned oil firm Rosneft in the presence of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

It was a deal that BP had wanted too, and thought it had managed to agree, until it was scuppered by a legal challenge from disgruntled Russian shareholders.

The Rosneft-Exxon deal was signed this week

Nick Gellatly, an oil analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said: "This is a new thing for Russia, as its current oil extraction is mainly done onshore, so it opens up a whole new frontier for them.

"There are challenges and restrictions to exploration - the climate will mean drilling will be restricted to certain parts of the year.

"[The deal] means Rosneft can share the cost of the exploration work as it has a large on-shore portfolio in Russia.

"In terms of other firms drilling in Russia, why not? The potential is there."

Earlier this month, a long-delayed plan by Shell to start drilling in US-controlled waters in the Arctic was finally given the go-ahead.

Shell's plan will see the company drill up to four shallow water exploratory wells off Alaska's northern coast beginning in July next year.

But it is not totally straightforward - the company still needs permits from the Environmental Protection Agency and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The oil giant is well aware of the potential in the region - Shell has submitted a plan to drill up to six wells in the Chukchi Sea in 2012 and 2013.

- Published22 September 2010

- Published31 August 2011

- Published30 August 2011