What is money, why do we trust it and has it become too confusing?

- Published

Did the global financial crisis undermine people's faith in money?

We dream about it, argue about it, worry about it, celebrate it, spend it, save it - but what exactly is money and why do we put our trust in it?

We invest it and gain it, and unfortunately sometimes lose it, and we give it value and worth - or at least we agree to give it a certain value. But what does it represent?

It used to be stones, or shells. It has sometimes been cigarettes, wives and, arguably, sex. Most-famously it has been gold and silver.

Now money is pieces of paper around which we have built a consensus in that we agree that it means something.

Central banks like the Bank of England hold the monopoly on producing this paper money - cold, hard cash as we know it.

This is known as "fiat currency", from the Latin "it shall be". It derives its value through government backing - but how did we make the shift from pieces of gold to pieces of paper?

Wartime design

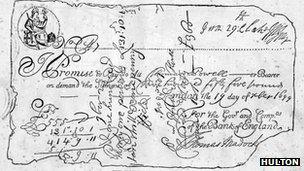

The oldest known bank-note issued by the Bank of England in 1699

Back in 1694, when the Bank of England was founded - to help fund the wars of the time - it would accept gold deposits and give out promissory notes in exchange, in effect promising the depositors that their gold would be safe and that they could come back and reclaim it sometime in the future.

Hence that promise to "pay the bearer on demand" that is still printed on each bank note today.

For a while, up until World War I - and for a brief period afterwards - England was on the Gold Standard.

What that meant was that every note that was printed by the Bank of England had to be backed by a certain amount of gold in its vaults.

But that is extremely constraining, especially when a country is at war, for example, when money needs to be more "elastic" - basically, when more money is needed to keep the economic wheels turning.

So now our paper money is not backed by anything tangible like gold or silver, other than that promise to pay the bearer - and the actions of the Bank of England.

"The reason the language is there," says Chris Salmon, the Bank of England's chief cashier, whose signature is on the new £50 note, "is to send a signal that we take our responsibility to maintain the value of the money very seriously, to maintain its purchasing power.

"The language is there to build confidence and trust, which are so important."

But recently our confidence in money has been shaken, even if we do not really understand what it is or how it works.

Imaginative act

So, other than those pieces of paper we take to the shops to hand over for goods or services, or even digital bits on a computer which are transferred across the world in a split second, what is this thing we call money?

"Money is a collective act of the imagination, and it's a thing which we have invested our credence in, and it works because we do that," says the writer John Lanchester, author of Whoops! Why Everybody Owes Everybody and No-One Can Pay.

But it has become clear that money has stopped working as it used to. The economic machine has seized up largely, it could be argued, because we made money too complicated and even the experts lost sight of what it really is.

John Lanchester argues that the financial whizz-kids thought they could control money and the inherent risk associated with playing about with it.

"The people inside the system were confident they had developed new tools to manage risk - that they had magically engineered away any risk.

"That is never true. Increased risk is just increased risk."

As a result, masses of cheap credit was pumped throughout the global financial system.

"The basic assumption was that the tide would not go out," says John Lanchester, "and the thing that astonished the world of money and caused the credit crunch - in fact it was the credit crunch - was the fact that the tide went out everywhere simultaneously."

Money auctions

Dylan Grice, a global strategist at the French bank Societe Generale, says another basic error that was made was that people confused money and credit.

"Credit requires that you pay someone back. Money does not. Money is yours. Money is just money, and that's the fundamental difference."

So banks can take your money on deposit but then they lend it out to someone else. "That is credit," says Grice.

"That is not money that they have created. The banking system creates credit and it's the central bank which creates money... and the last few years have seen a very clear case of the damage which has been caused by losing control of credit while trying to control money."

Recently, the UK's central bank, the Bank of England, has been creating billions of pounds of money, through the controversial policy of Quantitative Easing, or QE.

And that is because there is no longer enough money (or should that be credit?) flowing through the system, to oil the wheels of the economy.

Only the Bank of England can create money in the UK; and it can invent it out of thin air. The last time it did that was back in February, when it created another £50bn.

"What we do is expand our balance sheet and on one side we have the cash we're creating and on the other side, we have the gilts essentially that we're purchasing," explains Paul Fisher.

He is one of the nine members of the Monetary Policy Committee which meets to decide on interest rates and QE.

He is also the executive director for markets at the Bank of England, responsible for implementing QE. He argues that the Bank is not spending money, but that it is "giving out money in return for financial assets" - those gilts or treasury bonds which, in fact, are packages of government debt.

It does this through a system of auctions, three times a week, £1.5bn at a time.

The QE theory is that the Bank buys the government bonds from financial institutions like pension funds and insurance firms, the Bank credits their accounts with money which they, in turn, should spend out there in the wider economy.

Money elves

Paul Fisher says the greatest danger to the economy at the moment is not inflation but deflation. Remember, deflation does not just mean falling prices, which makes life difficult for producers, but also falling wages.

The Bank of England has issued £325bn through its quantitative easing programme

And for critics who argue that the Bank is creating an inflation time bomb by pumping billions more pounds into the system (it will be £325bn by May), Mr Fisher says: "We get the money back again at some point in the future, so it's a reversible transaction."

He is confident that without QE the economy would be in an even worse state than it now is, though, he does admit that "nobody pretends we can fine-tune this; the errors you can make on these calculations are very wide".

Other than questions about whether the policy has actually worked or not, there is another interesting little twist to QE.

"There's a slight thing we have to bear in mind," Paul Fisher says, "that it's illegal [under the Maastricht Treaty] for central banks to directly fund government spending, and we would fully support that."

The problem is that governments do fund some spending through the selling of their debt, or bonds. So, to get round the difficulty, Paul Fisher says that the Bank of England does not buy gilts directly from the government.

He explains: "We don't buy anything that the debt management office has issued in the week before or the week after our auctions. So we make sure that what we are buying is directly from the market… to separate it off from the idea of actually funding the government's deficit directly."

Some may see this as another bit of financial trickery.

For John Lanchester, with only a little bit of tongue-in-cheek, the QE policy is an example of the world of finance once again straying from reality and entering the realms of magic.

"It's almost easier if you just say that there are elves who make money and, when the money elves get to work, they sort of magically come up with it and then there's more of it," he says.

"I think that's probably more straightforward and makes just as much sense as explaining the mechanics of quantitative easing. It's elves."

Analysis is on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, 26 March at 20:30 BST and Sunday, 1 April at 21:30 BST.

You can listen again via the Radio 4 website or by downloading the podcast.

- Published1 November 2022

- Published18 March 2011

- Published14 March 2012