Gold v paper money: Which should we trust more?

- Published

Do we need to re-forge the link between money and something tangible?

A popular solution to the financial crisis has been to print more money, but is there another way of fixing our economy? Would the financial system be more stable if each pound, dollar or euro in our pocket was once again backed by gold?

Brian from Manchester has lost faith in money. After selling his house, he decided to turn his cash into something he says he can trust - gold.

"I started in 2005 and now I've got £200,000 worth - about half of what I own - in gold.

"If I kept all my money in the bank, the value of my work would either devalue over the long-term or it would be wiped out."

Brian's worry is that inflation will erode the value of his savings over time, or worse still, that fragile banks and governments will fail to protect them in another financial crisis.

And he is not alone in these fears.

Frances, who lives in London, sold her flat in 2008 and invested £40,000 of the profit in gold, which she bought via the internet and keeps in a vault in Switzerland.

"I don't fear a financial Armageddon," she tells Radio 4's Analysis, "but I do fear governments, in their desperate search for wealth, constantly printing more money to deal with the debt that they have at the expense of people like me.

"So I need to protect against that."

Both Frances and Brian have hitched their fortunes directly to the value of gold. They have put themselves on a gold standard, if you like.

The Bank of England has printed billions of pounds in its quantitative easing programme

Some economists and politicians argue that currencies need to do the same - that we need to reforge the link between money and something tangible.

As central banks around the world print trillions of pounds, euros and dollars in new money through measures like quantitative easing, which makes more sense: believing in money that is conjured out of thin air or believing in a yellow metal you cannot eat, put in your petrol tank or even take to the shops?

It is an argument that reveals deep divisions between economists.

In the green corner are those who would print more money to get us out of trouble and in the gold corner are the folks sometimes dismissively referred to as "gold bugs", who believe we are heading for a monetary reality check.

Detlev Schlichter is a former banker and the author of Paper Money Collapse and he says the current system is fatally flawed.

"The problem is that what we use as money can be created and produced by the privileged money producers - which are the central bank and the banking system.

"They can produce as much of this money as they like. And so the supply of this form of money is entirely elastic, it is entirely flexible."

Detlev Schlichter believes this will, ultimately, lead to people losing faith in our current system of elastic money and turning to something that does not stretch - like gold.

He advocates a radical free-market system where there are no central banks and where currencies - which are no longer tied to nation states - compete for credibility.

He believes that, in such a system, money that can be exchanged at the bank for something valuable - like gold - would be more attractive than a £10 note that can only be swapped for two £5 notes or change.

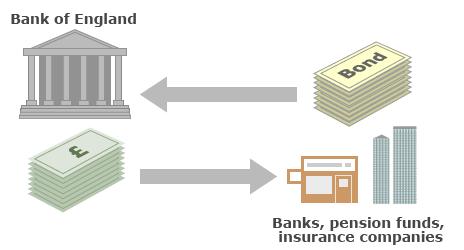

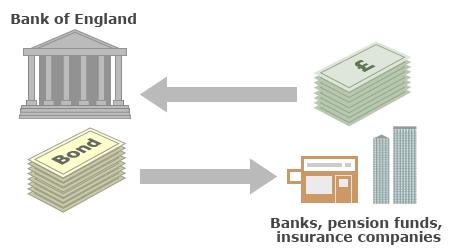

Quantitative Easing: Step by Step

First, with the permission of the Treasury, the Bank of England creates lots of money. It does this by just crediting its own bank account.

The Bank of England wants to use that cash to increase spending and boost the economy so it spends it, mainly on buying government bonds from financial firms such as banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

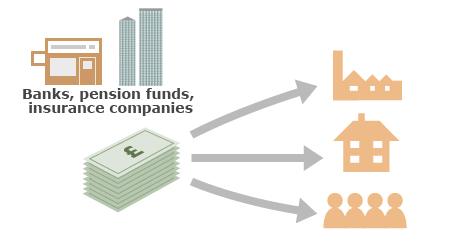

The Bank buying bonds makes them more expensive, so they are a less attractive investment. That means companies that have sold bonds may use the proceeds to invest in other companies or lend to individuals.

If banks, pension funds and insurance companies are more enthusiastic about lending to companies and individuals, the interest rates they charge should fall, so more money is spent and the economy is boosted.

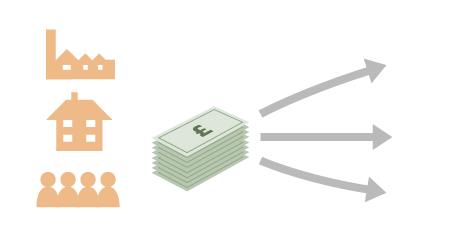

Theoretically, when the economy has recovered, the Bank of England sells the bonds it has bought and destroys the cash it receives. That means in the long term there has been no extra cash created.

For centuries money that was either made with or backed by gold was the norm.

The United States still operated under a form of the gold standard until President Richard Nixon abandoned it in 1971 because foreign governments started swapping the dollars they held for gold and the US started to run out of bullion.

And that, says mainstream thought, is the problem.

If the power to create more money is restricted, then as the economy grows, producing more goods and services, prices are likely to go down.

You might think that sounds good, but gold standard opponents argue there is a problem. After all, why would you buy something today if you know it is likely to be cheaper tomorrow? Consumers stop spending and the economy grinds to a halt - and this is why most economists are so scared of deflation.

DeAnne Julius of the think tank Chatham House was a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee - the body that decides how much money is in the system.

She says that if the amount of money in the system was limited by pegging it to gold it would limit economic growth, which is the last thing we need right now.

"I think to put your faith in gold as the basis of a country's monetary system would be extremely foolish," says Dr Julius.

And not just because it would limit growth but because, in practical, terms it would be chaos.

"We currently have less than one per cent of our GDP locked up as gold reserves in the Bank of England, so the kind of multiplier you would need to create pound notes which were very strictly tied to gold would be something of the order of four, five hundred times," she explains.

"Every time the price of gold moved, you would find the value of that money in your pocket leaping up and down - an extremely volatile and unstable way to run an economy."

This volatility of gold prices means it is also risky for investors like Brian and Frances, who have large amounts of their personal savings tied up in gold investments - £40,000 of gold might be worth less a year down the line.

The benefits of the current system, say central bankers, is that in times of trouble they can take remedial action, they can lower interest rates which encourage people to spend rather than save - which gives a boost to economic activity.

Detlev Schlichter says giving this sort of power to the monetary authorities is part of the problem, because it only postpones a financial crisis:

"The present system is a policy tool. It allows the central bank and by extension the state to manage the economy. It creates near-term booms but we pay for them with a big hangover at the end of the boom."

If we had stuck to the gold standard, it is probably true we would not be in the mess we are today.

Yes, our economy would be much smaller - but perhaps its foundations would be more solid if the only money in circulation was money that tied to something tangible like gold.

But in a world where monetary systems are controlled by central banks and governments, would a return to the gold standard work?

"You can't force a government to stay on gold, so therefore gold has no credibility," says Lord Lawson, chancellor of the exchequer in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher.

"Because [leaving the gold standard] has happened in economic history on many occasions, gold no longer exerts that discipline."

Countries have indeed abandoned gold when the going got tough - as they did in the 1930s and the 1970s. So if currencies did return to the gold standard, it might please the so-called "gold bugs" who have lost faith in paper money - but equally, it might introduce a new wave of sceptics, for whom the golden ring of trust has already been broken.

Listen to the full report on Analysis on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, 2 July at 20:00BST and Sunday, 8 July at 21:30BST. You can listen again on the Radio 4 website or by downloading the podcast.

- Published6 June 2012

- Published26 March 2012

- Published1 November 2022